Notes - Chapters 1-8 060724

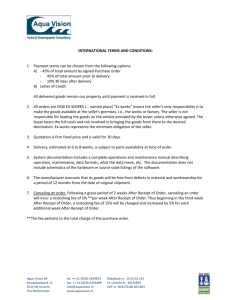

advertisement