View/Open - San Diego State University

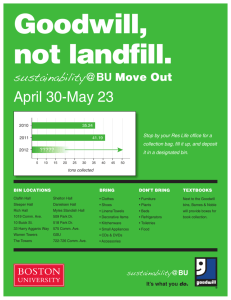

advertisement