cvi - sfasu

advertisement

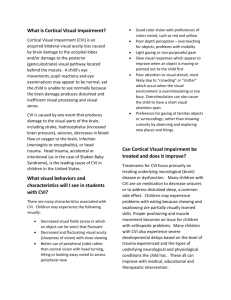

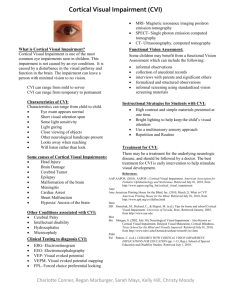

Cortical visual impairment (CVI) occurs when there is damage to the visual cortex, and/or the posterior visual pathways within the brain. The eye generally does not have any internal damage although CVI can also be evident in children who do have ocular damage. The reduction of vision is due to neurological damage which hinders visual stimulation from being organized and interpreted by the brain. As the name suggests, Cortical Visual Impairments affect the brain’s visual cortex and/or visual pathways that relay information from the eyes. Children who are cortically visually impaired have a medical history that involves neurological impairment due to conditions such as asphyxia, cerebral hemorrhage, infection of the central nervous system, and/or trauma. It is noted the following behaviors have been associated with cortical impairment: Visual performance can be quite variable, simply put, some days are better than others. Visual functioning can even change from hour to hour with some children. Visual field defects may also be associated with CVI due to specific neurological damage. Movement cues, especially in the peripheral fields can often stimulate a visual response. Visual interpretation may be improved for some children when they are actually moving as opposed to standing still. Color vision does not seem to be affected. Assessment of vision of children with CVI is an ongoing process that should be discussed several times during the first year and at least twice a year in preschool age children. The most typical feature of functioning of children with CVI is variation caused by changes in brain functions because of the basic condition and changes caused by varying effects of medications and fatigue. It is important to understand the base of information known about CVI must be analyzed to each child as an individual. Each characteristic of CVI may or may not fit an individual child. The information that does “fit” will help parents and teachers to design a home and/or school program that is tailored to each child’s needs. The vision of a child with CVI could impact the image quality changes, oculomotor deficiencies, changes in the function on the primary and the associative visual cortices, changes in compensatory functions. Objects of varying colors, textures, and shapes may be used with students who have CVI. Parents and teachers should decide what objects are typically used with the child during everyday activities or routines. To establish familiarity, the same object(s) should be used each time. Objects should be visually, tactually, and verbally presented at the onset of the activity and then talked about as the child experiences their function. The exact style of presentation will vary according to each child’s general learning style and needs. Light can be helpful in focusing students’ attention to objects or used in mobility adaptations. Light boxes are often used when working on skills such as tracking or targeting objects. Light Box Easter eggs with LEDs inside are easy to make and visually stimulating. A sound book modified to avoid visual distractions. The main focus is for the child with CVI to control visual input in order to avoid overstimulation. Reduce extraneous sensory information from the child’s “working/playing environment”. The use of touch should be a primary means of introducing information. Language is very important for information about the object or visual situation. Use labels that include description words. Tell the child what she/he is “seeing”. Currently, there is no precise treatment for CVI, and many rehabilitative measures are unproven. Clearly, there is a great need for additional research on treatment and management of this common and complex disorder. Richard Buckholt was born on July 22, 2007 the first son in a sea of women. The day after he was born, concerns about the size of his head were expressed. His head was extremely small; it did not make it on the growth chart. Tests were done for exploration. He appeared to being doing well, we thought all of the tests were precautionary and everything was fine. Richard had a head ultrasound and it revealed that he was missing part of his brain and had additional abnormalities. The ultrasound could not provide a clear picture and we were instructed to schedule a MRI to review his brain in further detail after he was three months of age. Thankfully, Richard was nursing well and he was able to come home to his family. The next few months were filled with tests and specialists. All of his major organs needed to be checked to rule out additional complications. The family saw just about all of his insides, all of which were functioning and doing well. The big test was the brain MRI. The MRI revealed that Richard’s brain was missing parts and the rest was abnormal. Today the family is still learning what all of this will mean for his life. Richard struggles with seizures which the family tries to regulate with medication. He is severely visually impaired. Richard has a G-J tube and is feed by j-tube (into his intestines) for about 20 hours a day. He struggles with chronic vomiting and Richard has been in and out of the hospital for them frequently. At home the family continues to pump his stomach, by a big suction machine, several times a day for about 30 minutes. Developmentally he is close to a newborn. He cannot hold his head for more than a few seconds. He needs constant full support. Richard sees a list of doctors and specialists on a regular basis: neurologist, ophthalmologist, occupational therapist, physical therapist, feeding therapist, vision therapist. One of the big questions for the family is his condition, handicap, label, etc. The mother states that it all depends on which doctor we are seeing and what part of his body that particular doctor is looking at. His family does know that the doctors, therapists, and insurance use these fancy labels to get Richard services, treatment or therapy but not one single term describes Richard. To the neurologist: ACC, seizure disorder, cerebral dysgensis, microcephaly, pontocerebellar hypoplasia To the occupational and physical therapists: cerebral palsy, developmental delays, mixed muscle tone To the ophthalmologist and vision therapist: cortical visual impairment, optic nerve hypoplasia To the GI doctor and feeding therapist: feeding difficulties, G-J tube, chronic vomiting His mother’s greatest concern is that Richard is currently not gaining weight at this time. He is currently losing hair and his skin is peeling. While tests have been done to try to find out why Richard was not sleeping this year it might all be adding up to malnutrition. Anthony, T. Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired (TSBVI). Cortical Visual Impairment An Overview of Current Knowledge. Retrieved July 15, 2013, from http://www.tsbvi.edu/programand-administrativeresources/3276-cortical-visual-impairment-anoverview-of-currentknowledge Hyvärinen, MD, L. (2004, ). American Printing House for the Blind. Understanding the Behaviours of Children With CVI.Retrieved July 17, 2013, from http://www.aph.org/cvi/articles/hyvarinen_1.html Demehak, M. University of Nevada, Reno. Tips for Home or School Cortical Visual Impairment. Retrieved July 18, 2013, from http://www.unr.edu/ndsip/tipsheets/cvi.pdf Good MD, W., Jan MD, J., Burden BS, S., Skoczenski PhD, A., & Candy PhD, R. American Printing House for the Blind. Recent advances in cortical visual impairment. Retrieved July 18, 2013, from http://www.aph.org/cvi/articles/good_1.html Welcome to APH CVI. (n.d.). American Printing House for the Blind. Retrieved July 19, 2013, from http://www.aph.org/cvi/index.html