Burton

advertisement

Fact Sheet by Keri Burton for SPE 516

_______________________________________________________________________

Condition:

Cortical Visual Impairment

Basic Description:

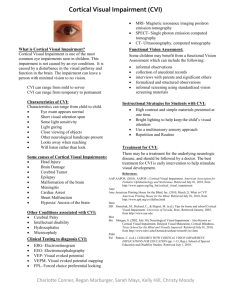

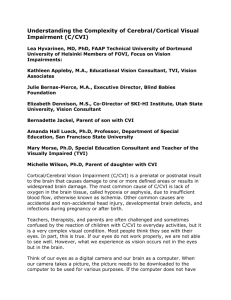

Cortical visual impairment (CVI) is a form of visual impairment that is caused

by a brain problem rather than an eye problem (the latter is sometimes termed

"ocular visual impairment" when discussed in contrast to cortical visual

impairment). Some people have both CVI and a form of ocular visual impairment

as well.

CVI is sometimes known as Delayed Visual Maturation because the person's

vision can sometimes seem (to an outside observer) to be improving over time.

This can be due to the person's learning how to make better use of the unusual

types of information that their malfunctioning visual system presents to them, and

to take into account the context and other clues in a piece of continuous

detective work. CVI is also sometimes known as Cortical Blindness, although

most people with CVI are not totally blind.

The parts of the visual system affected:

The retina and the brain

Effects on the visual system:

Vision appears to be variable: sometimes on, sometimes off; changing

minute by minute, day by day.

Many children with CVI may be able to use their peripheral vision more

effectively than their central vision.

One third of children with CVI are photophobic, others are compulsive light

gazers.

Color vision is generally preserved in children with CVI (color perception is

represented bilaterally in the brain, and is less susceptible to complete

elimination).

The vision of children with CVI has been described much like looking

through a piece of Swiss cheese.

Children may exhibit poor depth perception, influencing their ability to

reach for a target.

Vision may be better when either the visual target or the child is moving.

Difficulty with visual novelty (The individual prefers to look at old

objects, not new, and lacks visual curiosity.)

Visually attends in near space only

Difficulties with visual complexity/crowding (Individual performs

best when one sensory input is presented at a time, when the

surrounding environment lacks clutter, and the object being

presented is simple.)

Non-purposeful gaze/light gazing behaviors

Distinct color preference (Preferences are predominantly red and

yellow, but could be any color.)

Visual field deficits (It is not so much the severity of the field

loss, but where the field loss is located.)

Visual latency (The individual's visual responses are slow, often

delayed.)

Attraction to movement, especially rapid movements.

Common treatments, including medications:

Developing a proper diagnosis is the key to treating CVI. There are now

testing techniques that do not depend on the patient's words and actions, such

as FMRI scanning, or the use of electrodes to detect responses to stimuli in both

the retina and the brain. These can be used to verify that the problem is indeed

due to a visual cortex malfunction.

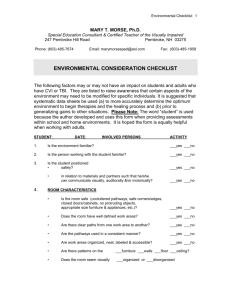

Younger patients, who have not reached developmental maturity will

require special learning environments that promote maximum stimulation of

residual vision. Such environmental stimulation may help to prevent

developmental delays. Research indicates that developmental milestones that

normally require vision ('reaching' and 'walking')are often delayed in children with

visual impairment, even in the absence of other disabilities.

Treatments that incorporate neural based stimulation methods and natural

developmental sequences are preferable such as: using movement, using high

contrast such as black on white or yellow pictures on a black background, use

boundaries to help eyes know where to focus, use stimulus of touch and vision

together, use selective colors (children usually have preferences), ensure proper

lighting and seating, simplify visual environment (students must know where to

focus), use stimulus materials that are common and used frequently, allow extra

time for processing, and use technology to enlarge and help students to focus.

Whether the condition is congenital, adventitious, progressive, or stable:

The disease is congenital or developed in an adult by a trauma or disease. As

children develop, their vision may improve.

Anticipated functional implications of the condition:

The degree of vision impairment can range from severe visual impairment

to total blindness. The degree of neurological damage and visual impairment

depends upon the time of onset, as well as the location and intensity of the insult.

It is a condition that indicates that the visual systems of the brain do not

consistently understand or interpret what the eyes see.

If CVI is from birth, many neural based stimulation methods and

developmental growth can cause the child to see and adapt better as time and

development continue to mature.

References:

http://www.blindbabies.org/factsheet_cvi.htm

http://www.aph.org/cvi/define.html

http://www.childrenshospital.org/az/Site2100/mainpageS2100P0.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cortical_visual_impairment

http://www.aph.org/cvi/articles/good_1.html

http://escholarship.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1176&context=education/tecplus

http://aapnews.aappublications.org/cgi/content/citation/30/5/17

Children are not born with a fully developed visual sense but acquire

their visual skills gradually. Delayed visual maturation is diagnosed

when young infants exhibit markedly delayed visual function, due to

various causes. Delayed visual development is a more appropriate

term because while the delayed visual function in most instances

improves, with appropriate management and with time; it only rarely

becomes entirely normal.

Diagnosing CVI is difficult. A diagnosis is usually made when visual performance is

poor but it is not possible to explain this from an eye examination. Before CVI was

widely known among professionals, some would conclude that the patient is faking their

problems or has for some reason engaged in self-deception. However, there are now

testing techniques that do not depend on the patient's words and actions, such as FMRI

scanning, or the use of electrodes to detect responses to stimuli in both the retina and the

brain. These can be used to verify that the problem is indeed due to a visual cortex

malfunction

Symptoms of CVI usually include several (but not necessarily all) of the following:

Variable vision. Visual ability can change from one day to the next but it can also

fluctuate from minute to minute, especially when the person is tired. When undertaking

critical activities, people with CVI should be prepared for their vision to fluctuate, by

taking precautions such as always carrying a white cane even if they don't always use it

to the full, or always having giant print available even if they don't always need it (for

example, consider the consequences of losing vision while giving a public speech).

Managing fatigue can reduce fluctuations but does not eliminate them.

One eye may perform significantly worse than the other, and depth perception can be

very limited (although not necessarily zero).

The field of view may be severely limited. The best vision might be in the centre (like

tunnel vision) but more often it is at some other point and it is difficult to tell what the

person is really looking at. Note that if the person also has a common ocular visual

impairment such as nystagmus then this can also affect which part(s) of the visual field

are best (sometimes there exists a certain gaze direction which minimises the nystagmus,

called a "null point") and both conditions come into play when restricting the field of

view.

Even though the field of view may be very narrow indeed, it is often possible for the

person to detect and track movement outside this area. (Movement is handled by the 'V5'

part of the visual cortex, which may have escaped the damage.) Sometimes a moving

object can be seen better than a stationary one; at other times the person can sense

movement but cannot identify what is moving (this can be annoying if the movement is

prolonged, and to escape the annoyance the person may have to either gaze right at the

movement or else obscure it). Sometimes it is possible for a person with CVI to see

things while moving their gaze around that they didn't detect when stationary. However,

movement that is too fast can be hard to track; some people find that fast-moving objects

"disappear".

Some objects may be easier to see than others. For example, the person may have

difficulty recognising faces or facial expressions but have fewer problems with written

materials. This is presumably due to the different way that the brain processes different

things.

Importance of colour and contrast. The brain's colour processing is distributed in such a

way that it is more difficult to damage, so people with CVI usually retain full perception

of colour. This can be used to advantage by colour-coding objects that might be hard to

identify otherwise. Sometimes yellow and red is easier to see, as long as this does not

give poor contrast between the object and the background.

Strong preference for a simplified view. When dealing with text, the person might prefer

to see only a small amount of it at once. This allows for more magnification, which may

be needed due to ocular visual impairments or in order to ensure that important things

such as letters are not completely hidden behind scotomas (small defects in parts of the

functioning visual field), but more importantly it simplifies the view and reduces the

chances of getting lost in it. However, the simplification of the view should not be done

in such a way that it requires too rapid a movement to navigate around a larger view,

since too much motion can cause problems (see above) although some is acceptable.

For the same reason (simplified view), the person may also dislike crowded rooms and

other situations where their functioning is dependent on making sense of a lot of visual

stimuli.