Tort law - David Friedman

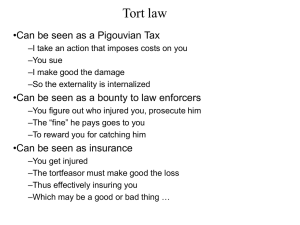

advertisement

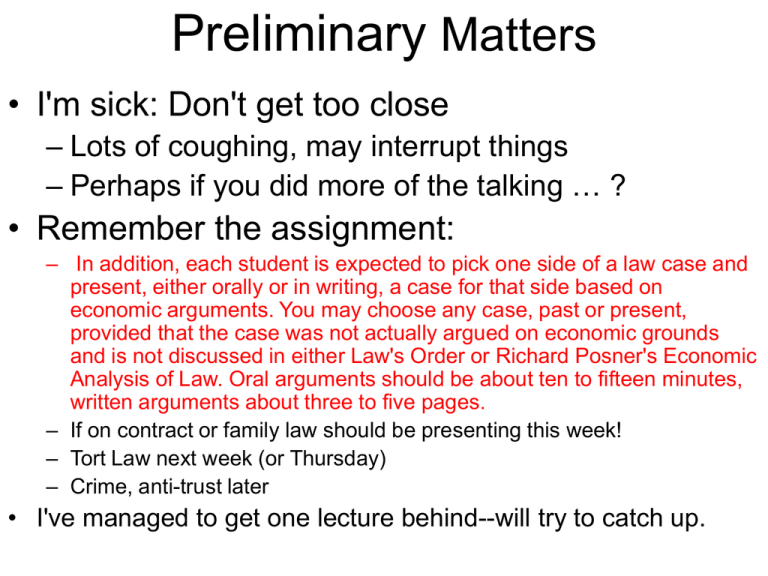

Preliminary Matters • I'm sick: Don't get too close – Lots of coughing, may interrupt things – Perhaps if you did more of the talking … ? • Remember the assignment: – In addition, each student is expected to pick one side of a law case and present, either orally or in writing, a case for that side based on economic arguments. You may choose any case, past or present, provided that the case was not actually argued on economic grounds and is not discussed in either Law's Order or Richard Posner's Economic Analysis of Law. Oral arguments should be about ten to fifteen minutes, written arguments about three to five pages. – If on contract or family law should be presenting this week! – Tort Law next week (or Thursday) – Crime, anti-trust later • I've managed to get one lecture behind--will try to catch up. Tort law •Can be seen as a Pigouvian Tax –I take an action that imposes costs on you –You sue –I make good the damage –So the externality is internalized •Can be seen as a bounty to law enforcers –You figure out who injured you, prosecute him –The “fine” he pays goes to you –To reward you for catching him •Can be seen as insurance –You get injured –The tortfeasor must make good the loss –Thus effectively insuring you –Which may be a good or bad thing … What is a tort? • A wrongful act • That imposes an externality – Competition is not a tort, because – The externality is pecuniary – What my competitor loses, his customers gain • Large enough to be worth using the legal system to deal with • Where a liability rule makes more sense than a property rule – My quitting isn’t a tort – Even if it hurts my employer badly – Because if he wants me, he can always offer to pay me more – I.e. a property rule rather than a liability rule – And I belong to me. Causation problems • What does it mean to say I caused your loss? – That “but for me” it wouldn’t have happened? – Not that simple. Consider • Coincidental causation – I stopped you to chat, then you went on – And a safe fell on your head – But for me you would still be alive • Redundant causation – Two hunters accidentally shoot a third – One through the head, one through the heart – Remove either one and he is still dead • Probabilistic causation – My radiation leak raised your risk of cancer a little – When you get cancer, did I cause it? Coincidental causation • The falling safe – But for my stopping my friend, he would be alive – But I couldn’t have known that – Ex ante, my stopping him did not make him more likely to die •We could reward me when I make the safe miss –But it’s a lot easier to let the two cases cancel –Base my liability on the ex ante effect –Hence I’m not liable –Note that this depends on what I knew –The man who just pushed the safe might know that my stopping my friend would kill him Forseeability • We don’t take the ex ante view in general – My liability for a car accident isn’t the average damage I could predict – But the actual damage – An issue we will return to • The general approach is to ask – What rule will give individuals the right incentive – In taking precautions – Or anything else • One problem we will be encountering is – The same rule may give an incentive on several margins – Tort damages affect the incentive of both tortfeasor and victim • What is the right incentive for the case of stopping my friend to talk? Redundant causation • My damages should equal the extra cost due to my action – – – – – But one bullet is enough to kill you, so The hunter who shot the man in the head did no damage With a bullet through the heart you don’t need a head And with a bullet through the head you don’t need a heart So both get off? • Law as incentive: I’m deciding whether to go hunting – One cost is that I might accidentally kill you – But it’s a little lower if someone else might kill you anyway – So my expected damage payment should be a little lower too The Real Case • Was two fires, not two hunters – Am I liable for damage due to a fire due to my negligence – If another fire was also started that would have burned down the same building? • Logic of the argument for letting them off is correct, but … – That legal rule opens a loophole for non-accidental shootings – And the alternative rule’s overdeterrence helps balance the underdeterrence – Due to not being able to collect damages equal to the full value of a life Probabilistic causation Reactor leak raises probability of cancer from 10% to 11% You get cancer, sue Defendant points out that the chance he caused it is only 1/11 And tort liability requires “more likely than not.” Could 100 cancer victims sue jointly, arguing that … Nine of the cases are the defendant’s fault Even though they don’t know which nine? Real Case Real case: DES Taken by pregnant mothers, caused a small probability of a problem When their daughters reached puberty In the public domain, produced by many firms, so … No records of who produced which dose Court assigned liability by market share, as a proxy for Probability that firm produced the dose that did the damage Should the case have been dismissed on forseeability grounds? Forseeable? “Knew or should have known?” Do we want drugs held back until tested on tens of thousands of humans For fourteen or fifteen years? What it would have taken. Efficient Accidents • The objective is not “zero traffic accidents” – We could get that by not driving – We could reduce the number of accidents by –A dagger sticking out of the steering wheel, or … –Wiring the air bag control to a hand grenade –(Gordon Tullock’s suggestions) • We want only efficient accidents, which means • Each party should take those precautions –That save more in expected accident costs –Than the precaution costs • If I pay the costs, it is in my interest to do that Unicausal Accidents • Assume the probability of the accident depends on only one party Strict liability I bear my costs, am liable for yours, so bear the total cost of the accident So it is in my interest to take all precautions worth taking Negligence I am liable if I did not take all cost justified precautions So if I don’t I bear all of the costs Which makes it in my interest to take all cost justified precautions So I do, so I’m not liable An efficient level of precautions makes me not negligent, not liable. Strict liability gives you more suits--all accidents Negligence gives you harder suits Since the court must determine not only causation and damage But also negligence Courts are not Omniscient But this assumes the court can tell what precautions I do and should take Suppose some precautions are either Unobservable--the court doesn’t know if I took them, or The court can’t tell if I should have taken them The usual term in the literature is “activity level” The court can tell whether I chose to drive today but not whether I should have So can’t judge me negligent for driving, only for how I drove Activity level is just one example of precautions court can’t observe or can’t judge An efficient level of observable precautions makes me not negligent, not liable. So a negligence rules results in an efficient level of observable precautions, strict liability in an efficient level of all precautions An argument for strict liability where unobservable precautions are very important “ultrahazardous activities: One precaution in keeping a pet tiger is not to Against if the unobservable are unimportant because not worth taking--Annie Lee Turner v Big Lake Oil. Dual Causality The chance of an accident depends on decisions by both parties We've been here before--a tort rerun of Coase vs Pigou Strict liability Some way of deciding who is the tortfeasor and who is the “victim.” Tortfeasor compensates victim for his loss Which eliminates the incentive for the "victim" to prevent the loss Negligence As in the unicausal case, it is in the tortfeasor’s interest not to be negligent So he won’t be negligent, so he won’t be liable So the victim won’t be compensated So it is in the victim’s interest to take all cost justified precautions Giving us the efficient outcome Provided that the court can observe and judge the tortfeasor’s precautions Fewer Rules than Meet the Eye No liability is the mirror image of strict liability Instead of “tortfeasor pays the whole cost, whatever he did” We have “victim pays the whole cost, whatever he did” So it is in the victim’s interest to take all cost justified precautions, but not the tortfeasor’ Strict liability with contributory negligence the mirror image of negligence liability One party (this time the victim) is liable unless he takes all cost justified precautions So he does, so he isn’t liable, so … The other party bears all the costs--making it in his interest to take all cost justified precautions. Back to Coase: "Tortfeasor" and "Victim" are not well defined "Victim": Party who bears the cost if the legal system does nothing? But an auto accident usually damages both cars. Choosing a Rule • We can work through the logic in • My simplified world – Only cars get hurt (victims), only tanks get sued (tortfeasors) – Cars never run into cars • If precautions by tanks are important, by cars are not – Strict liability gives the tanks the right incentive – The cars have the wrong incentive, but it doesn’t matter • If precautions by cars are important, by tanks are not – No liability gives the cars the right incentive – The tanks have the wrong incentive, but it doesn’t matter If Both … • If precautions by both are important – Negligence liability gives both cars and tanks the right incentive, if the court can tell whether tanks are negligent – Strict liability with a defense of contributory negligence gives the right incentive, if the court can tell whether cars are negligent – What if there are important unobservable precautions by both cars and tanks? • Tank pays a fine, but not to the car--double liability. But … who reports the accident? • Tank partly compensates car, so both have some but not enough incentive: Coinsurance • Court tries to distinguish cases by which party’s unobservable precautions matter more? • My world is artificial, but consider product liability. Manufacturers are tanks – An exploding coke bottle hurts the customer – Not Coca Cola – Maybe … Amount of damages • Pigouvian rule: charge the amount of the externality – Thus internalizing it, so tortfeasor takes the right precautions – Tort rule: make the injury whole. That sounds like the same thing • But not all torts result in a successful suit, so … – Tortfeasor faces a probability <1 of paying damages – So is underdeterred – Although he also may have legal costs, which overdeter? • How should we take account of legal costs? – – – – When result of committing a tort is that someone may sue Which leads to legal costs for both parties Are they part of what we must make good? Stay tuned--more next week Punitive damages: The Exception • History – – – Until recently rare, some question whether they existed Early cases: King’s messengers, shooting birds in someone else’s field Within the past century that changed • • • Awarded for deliberate or reckless tort No legal limit on or rule for the amount Theories of punitive damages, none entirely satisfactory 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Don’t exist--a misunderstanding of damages for real but hard to measure costs Exist to express moral disapproval. Why give the money to the victim? Exist to compensate for underterrence of torts often not successfully prosecuted (L&P) Why reckless torts, which are almost sure to be prosecuted? Exist to play safe where overdeterrence is not a problem (L&P) Why can’t a tort be deliberate and efficient? Exist to set damages>harm done where it is efficient to do so (DF) Exist to deter strategic torts (DF) Taking account of enforcement costs • The standard Pigouvian account ignores the cost of imposing the tax – – – – – But criminals have to be caught and punished Tortfeasors have to be identified and successfully prosecuted If a tort does net damage of $100--$1000 harm, $900 benefit But deterring it costs $200 It is more efficient not to--by setting a punishment <$900 • We will do this in more detail with criminal law, but … • What is the cost of deterring one more offense? • What is the benefit? • Keep doing it until benefit=cost for the next one. • At which point <P>=D-MC of deterrence. Verbal Version • Suppose some sort of tort is easily deterrable – A small increase in damages awarded a large decrease in torts – If it doesn’t happen it doesn’t have to be litigated – So marginal cost of deterrence is negative--more deterrence, less cost – So deter all inefficient offenses, plus slightly efficient ones – To save the cost of punishing them • But if a tort is hard to deter – – – – Higher damages more litigation cost/tort, almost as many torts Marginal cost of deterrence is positive--more deterrence, more cost So only deter offenses that are inefficient enough to be worth The cost of deterring them Punitive damages for deterrable torts? • Auto accident--tort as byproduct – – – – – Avoiding it is costly--not driving, precautions So perhaps changing damage level only has a small effect So ordinary damages<damage done “Make whole” but with narrow definition of costs And no adjustment for probability of collecting damages • Beating someone up--tort as product – If you are doing it deliberately it costs nothing not to – So perhaps it is easily deterred – Explaining punitive damages for deliberate torts? • But … – – – – If you have strong reasons to do it, then … There can still be a large cost to not doing it You don’t get the satisfaction of beating him up for insulting you … So perhaps not so easily deterrable Strategic Torts • Consider the bully back in the game theory chapter – He beats up A to deter B and C from doing things he doesn’t want them to – If ordinary damages don’t fully compensate – Then B and C may well be deterred – So the real damage done isn’t just to A • If we impose punitive damages then – B and C expect to be more than fully compensated, so aren’t deterred – And the damages better reflect the real harm • Consider the early cases – I humiliate you by shooting birds on your land • To deter other landowners from challenging my dominant political position • So punitive damages make sense – The King’s messengers mistreat a suspected author of seditious writings • To give other people an incentive not to do things that will get them suspected of it • So … Why pay the victim? • Argument against--Coaseian double causation – If we eliminate the cost to the victim, we also eliminate – His incentive not to be a victim • Argument for: Tort as bounty – It gives the victim an incentive to report and prosecute – Why give it to him instead of someone else? • He is likely to be the chief witness, and … • He already has some incentive--to deter torts against himself • Argument for: Tort as insurance? • Argument for: We have to give it to someone – Tort law is really a system of private prosecution, and … – A private prosecution system needs some way – To allocate the right to prosecute Product liability law • Caveat Emptor, Caveat Venditor, …? – Who pays when the coke bottle blows up – Buyer (for his medical costs) or Coke? • Caveat venditor: Seller is liable for (some? All? Invisible?) faults – Gives producer an incentive to efficiently reduce faults – Since he will pay for them. But … – That is only a problem if buyer is poorly informed • If buyer knows that one coke bottle in a thousand explodes • That lowers what he is willing to pay for a bottle of Coke • Which gives Coke an incentive to watch their quality control – Reduces buyers' incentive to take care in using the product. Coase. • Caveat emptor: Buyer takes the goods as he finds them – The right answer if the main cause of problems is buyer’s choices, or … – If buyer is well informed so reputation gives seller an adequate incentive Freedom of Contract? • Problem: Joint causation – Caveat emptor plus seller’s reputation works. – How about caveat venditor plus buyer’s reputation? – How about coinsurance? Partial liability, put the incentive where it does the most good – Or more complicated rules, such as • Caveat emptor for some sorts of defects, caveat venditor for others, or • Some version of negligence or strict plus contributory negligence • Suppose we let parties agree on the rule – If the default is caveat emptor, seller can provide a guarantee – If it is caveat venditor, buyer can sign a waiver • Still depends on the buyer’s information, but – Buyer doesn’t have to know if this bottle is defective – Or what fraction of bottles are defective – Only whether the guarantee is worth more to him than its price Tort as insurance? • Tort is sometimes seen as insurance – If you get injured, you get compensated – Makes sense as risk sharing? – Only if tort feasors can better spread risk • But it makes very poor insurance, because – It only covers a small subset of losses, and … – Forcing someone to pay is more expensive • When it is in his interest to have a reputation for not paying • Than when it is in his interest to have a reputation for paying • Why buy insurance if they won’t pay? Value of Information • Information is valuable because it affects decisions – So value depends on how likely it is to change the decision – And how large the benefit of the change is • Suppose a good costs $10 – It has an unknown defect that reduces its value by ten cents • There will be a very few people who value it at more than $10 but less than $10.10 • They will buy it, net social loss per purchase between zero and $.10 – Suppose the defect reduces value by $1.00 • About ten times as many people with values between $10 and $11 • And the net loss for each is between zero and $1 – So, roughly speaking, the social loss goes up a hundred fold when the importance of the defect goes up ten fold • More generally – Not only does the social cost of ignorance of defects increase with the importance of the defect – It increases more than linearly--roughly as the square – So warnings and such are much less important for small defects • Note that size here is – – – – Not the amount lost when the coke bottle explodes, but The effect of the risk on the value to a fully informed customer Roughly the amount of damage times its probability So even a very dangerous defect is “small” if very unlikely The threat of Global Cooling • We have some reason to expect warming over the next century • No special reason to expect cooling, but … • Earth is in an ice age – – – – We, fortunately, are in an interglacial Which typically last for tens of thousands of years This one might start ending in five thousand years Or next Friday • Global warming, at levels currently predicted – Raises temperature ~2°C in a century – Raises sea level a foot or so • The typical glacial – Covers Canada, England, Scandinavia, much of northern U.S. in ice – A mile thick over Chicago. What was Chicago. – Drops sea levels 500 feet or so, putting existing ports far inland. • Considering both probability and magnitude … Eggshell Skull: Vosburg v Putney • Suppose I carelessly hit you with a golf ball – It just happens that you are recovering from an auto accident – And the golf ball reshatters your healing skull – Doing enormous damage (The real case is even odder and somewhat suspicious) • Should damages be calculated – By actual damage done, or by – What the tortfeasor could expect the average damage to be? • Actual damage done results in the right incentive for the tortfeasor – – – – – Because, before teeing off, you average in the (unlikely) eggshell skulls The cyclists wearing protective helmets And everything between And the court can measure actual damage instead of estimating the average While ignoring the other tail--the case where there was no damage, no suit • But--double causation. Consider the victim’s incentives – He (probably) knows he is especially vulnerable, so, unlike the tortfeasor – Can take especially stringent precautions – Such as wearing a biking helmet when walking past a golf course Should Damages Payments be Lump Sum? • You persuade the court that I have tortiously crippled you – An estimated twenty years of lost employment, $50,000/year – Should you get a million now? – Or $50,000 each year you stay crippled? – (ignoring complications of accumulated interest) • What is the argument for the lump sum? • Against? Traffic on the highways ... cannot be conducted without exposing those whose persons or property are near it to some inevitable risk; and that being so, those who go on the highway, or have their property adjacent to it, may well be held to do so subject to their taking upon themselves the risk of injury ... and persons who ... pass near the warehouses where goods are being raised or lowered, certainly do so subject to the inevitable risk of accident. In neither case, therefore, can they recover without proof of want or care or skill occasioning the accident; ... .” Blackburn, J. (Fletcher v. Rylands L.R. 1 Ex. 265 (1866))