- AUCD Home

advertisement

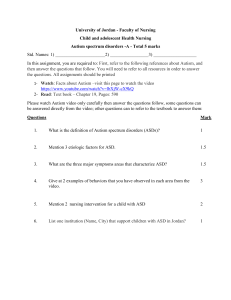

Automated Language Environment Analysis (LENA) in Understanding Language Profiles in Young Children with Down Syndrome, Autism, and Typical Development C. 1 Parikh , P. 1 Anand , J.O. 2,3 Edgin , & A. M. 1,3 Mastergeorge Family Studies and Human Development1; Department of Psychology2, University of Arizona, Sonoran UCEDD3 Methods Previous research suggests that early communication skills develop from experiences of successful interactions that occur in everyday contexts (Marder & Cholmain, 2006). Although there is variability in language proficiency at any given age, the impact of early experiences on language development is substantial (Weisleder & Fernald, 2013). For children who face significant language deficits and delays, such as children diagnosed with Down syndrome (DS) and autism spectrum disorders (ASD), the home environment may play an exceptionally important role in determining language acquisition and developmental trajectories (Haebig, McDuffie, & Weismer, 2013). Although children with DS and ASD display considerable individual variability, they are at an increased risk of impaired functioning in expressive language, poor speech intelligibility, and sociocommunicative skills (Tager-Flusberg et al., 2005; Thiemann-Bourque et al., 2014). Past research has highlighted that since fewer learning opportunities are available for children with DS and ASD, it is important to facilitate and foster the acquisition of language development in infancy. With the diversity of skills observed in these populations, it is imperative to distinguish language profiles that exist within the home (Marder & Cholmain, 2006; Naess et al., 2011). The present study utilized automated language environment analyses (LENA) in a naturalistic setting to explore differences among toddlers with DS, ASD, and typical development (TD): • Parent vocalizations (AWC); • Child vocalizations (CV); • Conversational turns (CT) DS ASD TD N = 42 N=9 N = 25 CA = 24.05 – 64.24m MA = 8 – 36m CA = 24.13 – 50.21m MA = 8 – 36m CA = 26.10 – 58.70m MA = 24 – 36m Males = 28 Females = 14 Males = 8 Females = 1 • Diagnosis of DS and autism was confirmed by karyotype report and/or other medical records. • Non-invasive LENA digital language processor (see figure 1) collected 16 continuous hours of audio recording. • Algorithms by LENA identified the frequency of words spoken by the child. • Conversational turn-taking and parent utterances were also examined. Results • Preliminary correlational analyses between the three variables of AWC, CV, and CT showed significant positive relations (p < .01) across the 3 groups. • A one-way ANOVA with diagnosis (AWC, CV, and CT) as the between-subjects factor suggested a significant main effect of diagnosis on CV: F (2, 73) = 9.34, p < 0.01 and CT: F (2, 72) = 5.36, p < 0.01. • No main effect of diagnosis was found for AWC: F (2, 73) = 1.30, p = 0.28. The University of Arizona Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities Average Audio Input in the Home 14000 Males = 16 Females = 9 • A total of N = 76 toddlers; 52 males and 24 females. Figure 1. A LENA digital language processor and a child-sized vest 16000 12000 Frequency Counts Background • Post-hoc Tukey HSD tests revealed significant differences in CV between DS &TD (p < 0.01) and DS & Autism (p < 0.05). • Post-hoc tests conducted on CT revealed significant differences only between DS &TD (p < 0.01). 10000 Down Syndrome Autism 8000 Typical Development 6000 4000 2000 0 Parent Utterances Child Vocalizations Conversational Turns Conclusions and Implications • Overall, the findings suggest that regardless of diagnosis, CV and CT patterns between the parent and child are important for language development. • Across the 3 groups, parental input dominates the majority of the audio environment. • For CV, individual differences are found across all 3 groups, highlighting the need for population-specific interventions. • The use of the LENA may contribute to improved measures of early expressive language as it exists in a natural context. • Implications for using this information in children’s language environment and parental behaviors may encourage opportunities for increased engagement that facilitate early and positive learning experiences for very young children. Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge the University of Arizona Down Syndrome Research Group, the Frances McClelland Institute, the University of Arizona LEND, and the Sonoran UCEDD for their contributions to this project. The funding for this project came from the following: The LuMind Foundation and Research Down syndrome.