micro - ibsgsection

advertisement

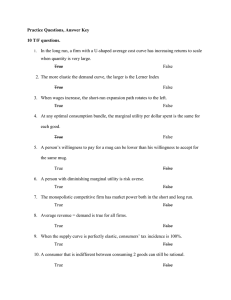

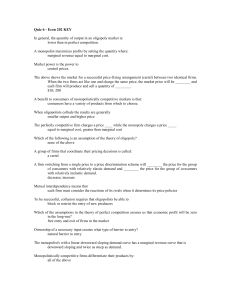

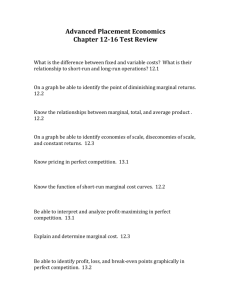

Short-Run Profit Maximization by a Competitive Firm • Marginal revenue equals marginal cost at a point at which the marginal cost curve is rising. CHOOSING OUTPUT IN THE SHORT RUN The Short-Run Profit of a Competitive Firm A Competitive Firm Making a Positive Profit In the short run, the competitive firm maximizes its profit by choosing an output q* at which its marginal cost MC is equal to the price P (or marginal revenue MR) of its product. The profit of the firm is measured by the rectangle ABCD. Any change in output, whether lower at q1 or higher at q2, will lead to lower profit. CHOOSING OUTPUT IN THE SHORT RUN The Short-Run Profit of a Competitive Firm A Competitive Firm Incurring Losses A competitive firm should shut down if price is below AVC. The firm may produce in the short run if price is greater than average variable cost. Shut-Down Rule: The firm should shut down if the price of the product is less than the average variable cost of production at the profit-maximizing output. THE COMPETITIVE FIRM’S SHORT-RUN SUPPLY CURVE The firm’s supply curve is the portion of the marginal cost curve for which marginal cost is greater than average variable cost. The Short-Run Supply Curve for a Competitive Firm In the short run, the firm chooses its output so that marginal cost MC is equal to price as long as the firm covers its average variable cost. The short-run supply curve is given by the crosshatched portion of the marginal cost curve. Producer Surplus in the Short Run ● producer surplus Sum over all units produced by a firm of differences between the market price of a good and the marginal cost of production. Producer Surplus for a Firm Alternatively, it is equal to rectangle ABCD because the sum of all marginal costs up to q* is equal to the variable costs of producing q*. Producer Surplus for a Market Producer Surplus in the Short Run Producer Surplus versus Profit Producer surplus = PS = R − VC Profit = π = R − VC − FC The producer surplus for a market is the area below the market price and above the market supply curve, between 0 and output Q*. CHOOSING OUTPUT IN THE LONG RUN Long-Run Competitive Equilibrium Entry and Exit Long-Run Competitive Equilibrium Initially the long-run equilibrium price of a product is $40 per unit, shown in (b) as the intersection of demand curve D and supply curve S1. In (a) we see that firms earn positive profits because longrun average cost reaches a minimum of $30 (at q2). Positive profit encourages entry of new firms and causes a shift to the right in the supply curve to S2, as shown in (b). The long-run equilibrium occurs at a price of $30, as shown in (a), where each firm earns zero profit and there is no incentive to enter or exit the industry. Long-Run Competitive Equilibrium • A long-run competitive equilibrium occurs when three conditions hold: 1. All firms in the industry are maximizing profit. 2.No firm has an incentive either to enter or exit the industry because all firms are earning zero economic profit. 3.The price of the product is such that the quantity supplied by the industry is equal to the quantity demanded by consumers. THE INDUSTRY’S LONG-RUN SUPPLY CURVE The Effects of a Tax on the firm Effect of an Output Tax on a Competitive Firm’s Output An output tax raises the firm’s marginal cost curve by the amount of the tax. The firm will reduce its output to the point at which the marginal cost plus the tax is equal to the price of the product. The Effects of a Tax on Industry Effect of an Output Tax on Industry Output An output tax placed on all firms in a competitive market shifts the supply curve for the industry upward by the amount of the tax. This shift raises the market price of the product and lowers the total output of the industry. CONSUMER SURPLUS . EVALUATING THE GAINS AND LOSSES FROM GOVERNMENT POLICIES— CONSUMER AND PRODUCER SURPLUS Review of Consumer and Producer Surplus EVALUATING THE GAINS AND LOSSES FROM GOVERNMENT POLICIES— CONSUMER AND PRODUCER SURPLUS ● welfare effects producers Gains and losses to consumers and Change in Consumer and Producer Surplus from. Price Controls Gain in consumer surplus consumers who can buy=A for Loss in consumer surplus who cannot buy=B The gain to consumers is the difference between rectangle A and triangle B. Loss in producer surplus for producers who remain in the market=A Loss in producer surplus since prodn. Has reduced= C The loss to producers is the sum of rectangle A and triangle C. Triangles B and C together measure the deadweight loss from price controls.(A-B)+(-A-C)=total change in surplus. ● deadweight loss Net loss of total (consumer plus producer) surplus. Effect of Price Controls When Demand Is Inelastic If demand is sufficiently inelastic, triangle B can be larger than rectangle A. In this case, consumers suffer a net loss from price controls. Efficiency of a Competitive market • Economic efficiency is maximization of aggregate consumer and producer surplus. • Policy interventions in perfect markets leads to dead weight loss but may still be required to avoid negative externalities and demerit goods.(taxi fares, liquor licenses, import quotas, tariff, Monopoly • • • • • • • • • • • One seller No close substitute Firm is a price maker. There are barriers to entry It is possible to earn abnormal profits in the short and long run Barriers to entry(Legal, control over raw material, know-how, economies of scale, small market size, superior efficiency, copyrights, patents) Profit maximisation leads to higher prices and lower output than perfect competition Governments are concerned about monopolies exploiting consumers. Price is greater than MR Monopolies are allocatively inefficient since P>MC Monoploist is also productively inefficient since because it is not producing at the minimum of the acerage cost curve. MONOPOLY • Average Revenue and Marginal Revenue ● marginal revenue Change in revenue resulting from a one-unit increase in output. TABLE 10.1 Price (P) Total, Marginal, and Average Revenue Quantity (Q) Total Revenue (R) Marginal Revenue (MR) Average Revenue (AR) 6 0 0 --- --- 5 1 5 5 5 4 2 8 3 4 3 3 9 1 3 2 4 8 -1 2 1 5 5 -3 1 MONOPOLY • Average Revenue and Marginal Revenue Average and Marginal Revenue Average and marginal revenue are shown for the demand curve P = 6 − Q. The Monopolist’s Output Decision Profit Is Maximized When Marginal Revenue Equals Marginal Cost Q* is the output level at which MR = MC. If the firm produces a smaller output—say, Q1—it sacrifices some profit because the extra revenue that could be earned from producing and selling the units between Q1 and Q* exceeds the cost of producing them. Similarly, expanding output from Q* to Q2 would reduce profit because the additional cost would exceed the additional revenue. Monopoly making losses A Rule of Thumb for Pricing Marginal cost should be equal to P plus P(1/Ed). The markup should be equal to minus the inverse of elasticity of demand. Thus price is a markup over cost. The markup over marginal cost as a percentage of price = (P-MC)/P. In perfect competition: P=MC In monopoly: price exceeds MC by an amount that depends inversely on the elasticity of demand. If demand is very elastic, price will be very close to MC. Supply curve • There is no one to one relationship between price and quantity produced. • Output decision depends not only on MC but also on shape of the demand curve. • shift in demand curve can lead to changes in both price and output • A competitive industry supplies a specific quantity at every price but in monoply, there can be same quantity supplied at different price depending on the elasticity or different quantity supplied at same price. Effect on equilibrium on Shifts in Demand Upward shift in the demand curve may result in more quantity and higher , lower or same price. Effect in demand depend on the extent of the shift and on the price elasticity of demand. If elasticity has increased it is profitable for the monopolist to not only increase the output but also lower the price. Effect on equilibrium on increase in cost • An increase in costs increases price and reduces quantity • Effect of specific tax- increases price and reduces quantity • Effect of lump sum tax- the equilibrium does not change as MC curve is not affected. The total profits of the monopolist reduces. MONOPOLY POWER Measuring Monopoly Power Remember the important distinction between a perfectly competitive firm and a firm with monopoly power: For the competitive firm, price equals marginal cost; for the firm with monopoly power, price exceeds marginal cost. ● Lerner Index of Monopoly Power Measure of monopoly power calculated as excess of price over marginal cost as a fraction of price. Mathematically: This index of monopoly power can also be expressed in terms of the elasticity of demand facing the firm. (10.4) Elasticity of Demand and Price Markup • The markup (P − MC)/P is equal to minus the inverse of the elasticity of demand facing the firm. • If the firm’s demand is elastic the markup is small and the firm has little monopoly power (eg: grocery stores vs. supermarket chains) • The opposite is true if demand is relatively inelastic (eg. Designer jeans) SOURCES OF MONOPOLY POWER The Elasticity of Market Demand If there is only one firm—a pure monopolist—its demand curve is the market demand curve. Because the demand for oil is fairly inelastic (at least in the short run), OPEC could raise oil prices far above marginal production cost during the 1970s and early 1980s. Because the demands for such commodities as coffee, cocoa, tin, and copper are much more elastic, attempts by producers to cartelize these markets and raise prices have largely failed. In each case, the elasticity of market demand limits the potential monopoly power of individual producers. SOURCES OF MONOPOLY POWER The Number of Firms When only a few firms account for most of the sales in a market, we say that the market is highly concentrated. ● barrier to entry Condition that impedes entry by new competitors. SOURCES OF MONOPOLY POWER The Interaction Among Firms Firms might compete aggressively, undercutting one another’s prices to capture more market share. This could drive prices down to nearly competitive levels. Firms might even collude (in violation of the antitrust laws), agreeing to limit output and raise prices. Because raising prices in concert rather than individually is more likely to be profitable, collusion can generate substantial monopoly power. Other measures of monopoly power • Cross elasticity of demand – The value is zero in case for pure monopoly and infinity for perfect markets. – Lower this value, greater will be the degree of monopoly power. THE SOCIAL COSTS OF MONOPOLY POWER Deadweight Loss from Monopoly Power The shaded rectangle and triangles show changes in consumer and producer surplus when moving from competitive price and quantity, Pc and Qc, to a monopolist’s price and quantity, Pm and Qm. Because of the higher price, consumers lose A + B and producer gains A − C. The deadweight loss is B + C. The dead weight loss is the social cost of monoply/. Comparison bt. Perfect competition and monopoly • Monopolist can either determine his output or price not both whereas in perfect competition he can decide only output. • In long run, output will be lower and price higher at profit maximisation. This is because firm makes normal profits at minimum cost in long run under perfect comp. and monopoly firms make abnormal profits. • At eq. elasticity can be any value in perfect comp but in monopoly it is less greater than 1. • In monopoly there is no certainty that firm will incur min. cost at long run. • Supply firm is not uniquely determined in monopoly. • In perfect comp. there are no abnormal profits in the long run. PRICING ●If a firm can charge only one price for all its customers, that price will be P* and the quantity produced will be Q*. Ideally, the firm would like to charge a higher price to consumers willing to pay more than P*, thereby capturing some of the consumer surplus under region A of the demand curve. The firm would also like to sell to consumers willing to pay prices lower than P*, but only if doing so does not entail lowering the price to other consumers. In that way, the firm could also capture some of the surplus under region B of the demand curve. CAPTURING CONSUMER SURPLUS Capturing Consumer Surplus ●Customers in region A can pay more and in B (capturing consumer surplus) , since P>MC, prices could be reduced. Firms can have different prices according to where customers are along the demand curve. If it charges some customers higher than P* (say P1) and some lower than P*(say P2) and some P* it can capture customer surplus. PRICE DISCRIMINATION ● first-degree price discrimination Practice of charging each customer its maximum price. Additional Profit from Perfect First-Degree Price Discrimination When only a single price, P*, is charged, the firm’s variable profit is the area between the marginal revenue and marginal cost curves. Variable profit is yellow area. Consumer surplus is the black triangle. Because the firm charges each consumer her reservation price, it is profitable to expand output to Q** (AR=MC). Variable profit is yellow plus blue area. With perfect price discrimination, this profit expands to the area between the demand curve and the marginal cost curve. Now it produces Q** where AR=MC ● variable profit (profit ignoring fixed cost) Sum of profits on each incremental unit produced by a firm; i.e., profit ignoring fixed costs. Variable profit is increased. All consumer surplus has been captured. PRICE DISCRIMINATION First-Degree Price Discrimination Perfect Price Discrimination The additional profit from producing and selling an incremental unit is now the difference between demand and marginal cost. Imperfect Price Discrimination First-Degree Price Discrimination in Practice Firms usually don’t know the reservation price of every consumer, but sometimes reservation prices can be roughly identified. Here, six different prices are charged. The firm earns higher profits, but some consumers may also benefit. With a single price P*4, there are fewer consumers. The consumers who now pay P5 or P6 enjoy a surplus. PRICE DISCRIMINATION Second-Degree Price Discrimination Second-Degree Price Discrimination ● second-degree price discrimination Practice of charging different prices per unit for different quantities of the same good or service. ● block pricing Practice of charging different prices for different quantities or “blocks” of a good. Eg: electric power, natural gas, water etc. Different prices are charged for different quantities, or “blocks,” of the same good. Here, there are three blocks, with corresponding prices P1, P2, and P3. There are also economies of scale, and average and marginal costs are declining. Seconddegree price discrimination can then make consumers better off by expanding output and lowering cost. Third-Degree Price Discrimination ● third-degree price discrimination Practice of dividing consumers into two or more groups with separate demand curves and charging different prices to each group. Eg: airlines, railways, liquor, canned food, student discounts. Creating Consumer Groups If third-degree price discrimination is feasible, how should the firm decide what price to charge each group of consumers? • We know that however much is produced, total output should be divided between the groups of customers so that marginal revenues for each group are equal. • We know that total output must be such that the marginal revenue for each group of consumers is equal to the marginal cost of production. Third-Degree Price Discrimination Determining Relative Prices (11.2) Third-Degree Price Discrimination Consumers are divided into two groups, with separate demand curves for each group. The optimal prices and quantities are such that the marginal revenue from each group is the same and equal to marginal cost. Here group 1, with demand curve D1, is charged P1, and group 2, with the more elastic demand curve D2, is charged the lower price P2. Marginal cost depends on the total quantity produced QT. Note that Q1 and Q2 are chosen so that MR1 = MR2 = MC. PRICE DISCRIMINATION Third-Degree Price Discrimination Determining Relative Prices No Sales to Smaller Market Even if third-degree price discrimination is feasible, it may not pay to sell to both groups of consumers if marginal cost is rising. Here the first group of consumers, with demand D1, are not willing to pay much for the product. It is unprofitable to sell to them because the price would have to be too low to compensate for the resulting increase in marginal cost. Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly ● monopolistic competition Market in which firms can enter freely, each producing its own brand or version of a differentiated product. ● oligopoly Market in which only a few firms compete with one another, and entry by new firms is impeded. ● cartel Market in which some or all firms explicitly collude, coordinating prices and output levels to maximize joint profits. MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION • Features A monopolistically competitive market has two key characteristics: 1. Firms compete by selling differentiated products that are highly substitutable for one another but not perfect substitutes. In other words, the cross-price elasticities of demand are large but not infinite. There is free entry and exit: it is relatively easy for new firms to enter the market with their own brands and for existing firms to leave if their products become unprofitable. 2. Limited monopoly power 3. Eg: toothpaste, shaving cream, shampoo, soap, bicycles, reatail trade 4. Product differentiation creates brand loyalty and gives rise to downward sloping demand curve 5. Product differentiation provides the rationale of selling expenses. 6. Product changes, advertising and salesmanship are the main means of product differentiation. A Monopolistically Competitive Firm in the Short Run Because the firm is the only producer of its brand, it faces a downward-sloping demand curve. Price exceeds marginal cost and the firm has monopoly power. In the short run, described in part (a), price also exceeds average cost, and the firm earns profits shown by the yellowshaded rectangle. Equilibrium in the short and Long Run In the long run, these profits attract new firms with competing brands. The firm’s market share falls, and its demand curve shifts downward. In long-run equilibrium, described in part (b), price equals average cost, so the firm earns zero profit even though it has monopoly power. More output can be produced at lowest cost , therefore excess capacity exists. If no. of firms are reduced and output of each is increased, cost will reduce. Monopolistic Competition and Economic Efficiency Comparison of Monopolistically Competitive Equilibrium and Perfectly competitive Equilibrium Under perfect competition, price equals marginal cost. The demand curve facing the firm is horizontal, so the zeroprofit point occurs at the point of minimum average cost. Monopolistic Competition and Economic Efficiency Under monopolistic competition, price exceeds marginal cost. Thus there is a deadweight loss, as shown by the yellowshaded area. The demand curve is downward-sloping, so the zero profit point is to the left of the point of minimum average cost. In evaluating monopolistic competition, these inefficiencies must be balanced against the gains to consumers from product diversity. Impact of advertising and other costs of prodn and selling • Advertising and selling costs increase AC. • Advertising is an alternative to reduction in prices. • In the long run, profits will disappear since new entrants will copy advertising campaigns. • Consumers do not benefit since prices do not fall due to higher selling costs. • As a result of advertising, each monopolistically competitive firm produces more than it would otherwise which reduces excess capacity but consumers do not benefit since prices are not lowered. • Continuous product development also leads to more cost and more profits but more profits can disappear in the long run due to copying. OLIGOPOLY Only a few firms account for most or all of total production. A rule of thumb is that an oligopoly exists when the top five firms in the market account for more than 60% of total market sales. In oligopolistic markets, the products may or may not be differentiated. Product branding: Each firm in the market is selling a branded product. Entry barriers: Entry barriers maintain supernormal profits for the dominant firms. It is possible for many smaller firms to operate on the periphery of an oligopolistic market, but none of them is large enough to have any significant effect on prices and output Inter-dependent decision-making: Inter-dependence means that firms must take into account the likely reactions of their rivals to any change in price, output or forms of non-price competition. Non-price competition: Non-price competition is a consistent feature of the competitive strategies of oligopolistic firms. (advertising, after-sales service, free gifts) •Examples of oligopolistic industries include automobiles, steel, aluminum, petrochemicals, electrical equipment, and computers. NON-PRICE COMPETITION • Practiced by oligopoly and monopolistic competition. Various forms: Competitive advertising – to reinforce product differentiation and harden brand loyalty. Promotional offers – eg. Household detergent, toothpaste, shampoo (buy 2 get 1 free), (25% extra at no extra cost). Extended guarantees/after sales service – esp. for consumer durables, by offering free spare parts, labour guarantee. Better credit facility Attractive gift wrappings KINKED DEMAND CURVE • ASSUMPTIONS • There are many firms • Each produces a product which is a close substitute. • Product qualities are constant, advertising expenditures are 0. • Rivals lower the price if he lowers the price but do not raise it if he raises it. £ Stable price under conditions of a kinked demand curve MC2 MC1 P1 a D = AR b O Q Q1 MR KINKED DEMAND CURVE THEORY • If the firm lowers its price below OP1, its rivals will follow. If the other firms do follow A’s price changes, then there is going to be less substitution taking place and the demand for A’s product is going to be relatively INELASTIC (steep slope). Its demand will expand along the relatively inelastic section of the demand curve below OP1 and total revenue will fall. If the firm raises its price above OP1, none of its competitors will follow. If the other firms do not follow then the demand for A’s product will be relatively ELASTIC (flat slope). Its demand for prices above OP1 will contract along the relatively elastic section of the demand curve and total revenue will fall. • As a result of action and non-reaction to price changes, an oligopolist is faced with a kinked demand curve at OP1. • Price rigidity is due to the kinked demand curve and the resulting discontinuity in the MR curve. • There is limited real-world evidence for the kinked demand curve model. The theory can be criticised for not explaining why firms start out at the equilibrium price and quantity. That said it is one possible model of how firms in an oligopoly might behave if they have to consider the likely responses of their rivals. Kinked Demand Curve • When firms believe that their product is a close substitute for their competitor’s product, they do not have much incentive to change price: • A price decrease will be matched, so they have nothing to gain by lowering price. • A price increase will not be matched, so they have a lot to lose by raising price. 54 Changing cost conditions Even though MC may be rising or falling, MC=MR in the portion of discontinuity will leave price and output unchanged at OP1 and OQ1. Changes in costs has no effect on profit maximising price and out put because the firm is still producing where MC=MR. ADVANTAGES OF OLIGOPOLY • When firms collude – monopoly –supernormal profit – extra profit – extra capital – to fund R&D – benefit to consumer. • Product differentiation – non-price competition– greater variety to consumers. • Price stability/rigidity – helps in planning, reduce uncertainty. DISADVANTAGES OF OLIGOPOLY • Collusive oligopoly if they agree upon output – no variety and improvement in quality – bad for consumers. o Acting like a monopoly Restrict output and charge a higher price Producer sovereignty Consumer sovereignty not respected Greater inequality in income (supernormal profits) Collusive Oligopoly • To avoid uncertainty, oligopolistst may enter into collusive agreements. • A cartel arrangement occurs when the firms in an industry cooperate and act together as if they were a monopoly. • Cartel arrangements may be tacit or formal • Conditions that influence the formation of cartels – – – – – – Small number of firms in the industry Geographical proximity of the firms Homogeneous products Stage of the business cycle Difficult entry Uniform cost conditions Cartels aimed at joint profit maximisation • The central agency will calculate the market demand curve and the corresponding MR curve. • The market MC is obtained from horizontal summation of individual MC curves. • The joint profit is maximized where MC=MR. • Allocation of output between A and B is determined by equating common MR with MC1 and MC2. • Equilibrium condition: MR= MC1=MC2 • • • • • Profits for each firm are shown in blue. We assume that each firm earns profits only from its own sales. Firms may earn different levels of profit. Combined profits are maximized. Incentive for firms to cheat on agreement. Cartels are unstable. Cartels aimed at market-sharing by non-price competition • Firms agree to share the market and agree on a common price which is set by bargaining such that all members make some profits. The members can vary the style of the product and can compete on a non-price basis. • This form of cartel is more unstable as low cost firms will to break away and charge a lower price. This may lead to price war and instability. Sharing of the market by agreement on quotas • There is an agreement on the quantity that each member may sell at the agreed price. • Shares on the basis of cost differential is decided by bargaining. • Conditions for Cartel Success • Agreement on price and production levels • Potential for monopoly power. Price leadership • Price leadership is another form of collusion in oligopoly. • Types of price leadership – Price leadership by a low-cost firm – By a dominant firm – Barometric price leadership Dominant Price Leadership – One firm is recognized as the industry leader. – Dominant firm sets price with the realization that the smaller firms will follow and charge the same price. – Determining the optimal price is illustrated in the following graphs. Price Leadership • DT is the demand curve facing the entire industry. • MCR is the summation of the marginal cost curves of all of the follower firms. You can think of MCR as a supply curve for these firms. • In choosing its price, the dominant firm has to consider the amount supplied by the follower firms. Price Leadership • For any price chosen by the dominant firm, some of the market demand will be satisfied by the follower firms. The “residual” is left for the dominant firm. • The demand curve facing the dominant firm is found by subtracting MCR from DT. This “residual demand curve” is labeled DD. Price Leadership • To determine price, the dominant firm equates its marginal cost with the marginal revenue from its residual demand curve. • The dominant firm sells A units and the rest of the demand (QT – A) is supplied by the follower firms. Follower Supply Follower Supply Barometric Price Leadership – One firm in an industry will initiate a price change in response to economic conditions. – The other firms may or may not follow this leader. – Leader may change. Game theory • A mathematical technique for analyzing the decisions of interdependent oligopolistic firms in uncertain situations. • A “game” is simply a competitive situation where two or more firms or individuals pursue their interests and no person can dictate the final outcome or “payoff”. • Players choose their strategy without certain knowledge of the other players strategies, but may eventually learn which way the opposition is leaning. 69 Elements of a Game • Basic elements – The players – The strategies – The payoffs • Payoff matrix – The fundamental tool of game theory. – This is simply a way of organizing the potential outcomes of a given game in a table that describes the payoffs in a game for each possible combination of strategies 70 Strategies • Dominant strategy – A strategy that yields a higher payoff no matter what the other players in a game choose. The dominant strategy is each player’s unique best strategy regardless of the other players’ action • Dominated strategy – Any other strategy available to a player who has a dominant strategy • Nash Equilibrium – Any combination of strategies in which each player’s strategy is his best choice, given the other players’ strategies – IOW: Nash equilibrium is achieved when all players are playing their best strategy given what the other players are doing. 71 Prisoner’s dilemma Prisoner A Confess Prisoner B Deny Confess (3 years, 3 years) (1 year, 10 years) Deny 10 years, 1 year) (2 years, 2 years) A simple game and payoff matrix • Duopoly situation – each of the two firms A and B must decide whether to mount an expensive advertising campaign. • If each firm decides not to advertise, each will earn a profit of $50,000. • If one firm advertises and the other does not, the firm that does will increase its profits by 50% to $75,000, and drive the competition into a loss. • If both firms advertise, they will earn $10,000 each because the advertising expense forced by competition wipes out large profits 73 Example continued… • If firms could agree to collude, the optimal strategy would obviously be to not advertise – maximize joint profits = $100,000 – Let’s assume they cannot collude, and therefore do not know what the competition is doing. • A “Dominant Strategy” is the one that is best no matter what the opposition does. 74 Dominant strategy and nash equilibirum • Payoff matrix for advertising game Firm B Firm A advertise Don’t advertise Advertise 10,5 15, 0 Don’t advertise 6,8 10,2 Firm B Firm A advertise Don’t advertise Advertise 10,5 15, 0 Don’t advertise 6,8 20,2 Nash equilibrium • It is a set of strategies such that each player is doing the best it can given the actions of its opponents. The strategies are stable as players do not have any incentive to deviate. • Dominant strategy equilibrium is a special case of Nash equilibrium. Firm B Firm A Crispy Sweet Crispy -5,-5 10,10 Sweet 10,10 -5,-5 • If firm 1 indicates through a price release that that it is about to introduce sweet cereal, the nash equilibrium will be the left hand corner of the matrix and will be a stable one. Pricing Strategies • Penetration Pricing-Price set to ‘penetrate the market’,‘Low’ price to secure high volumes, typical in mass market products – chocolate bars, food stuffs, household goods, etc., useful in launching new products. • Market Skimming-High price, Low volumes, Suitable for products that have short life cycles or which will face competition at some point in the future (e.g. after a patent runs out) • Examples include: Playstation, jewellery, digital technology, new DVDs, etc. • Value Pricing-Price set in accordance with customer perceptions about the value of the product/service. • Loss Leader-Goods/services deliberately sold below cost to encourage sales elsewhere, e.g. ‘Free’ mobile phone when taking on contract package • Psychological Pricing-Used to play on consumer perceptions, eg: 99/, 999/-,9.99% • Going Rate (Price Leadership)-In case of price leader, rivals have difficulty in competing on price – too high and they lose market share, too low and the price leader would match price and force smaller rival out of market. Eg: banks, petrol, supermarkets, electrical goods • Tender Pricing • Price Discrimination • Destroyer/Predatory Pricing • Full Cost Pricing- to cover both fixed and variable costs • Absorption Cost Pricing- Price set to ‘absorb’ some of the fixed costs of production • Marginal Cost Pricing-Particularly relevant in transport where fixed costs may be relatively high • Target Pricing • Cost-Plus Pricing- AC plus a mark up Practice sums • Quantity demanded of a product decreases from 4000 units to 3000 units wheb price of the product increases from Rs.40 to Rs.45. If income effect is estimated to be 900, substitution effect of the price change is…? • MU of good X is 300 utils and its price is Rs.12.If price of good Y is Rs.30,the MU of good Y at equilibrium is…? • A consumer is willing to buy 100 units of a product at a price of Rs.10. If the current market price of the product is Rs.9, consumer surplus is? • Assume that utility can be measured in Rs. From the utility schedule given below, find how many cokes the consumer would consume at the price of Rs.9 per coke. Coke Total utility (Rs.) 1 30 2 45 3 54 4 59 5 59 • Vinod has a monthly income of Rs.340. Being an addict to fruit juices, he spends all his income on Apple, Mango, and orange juices. The prevailing prices of apple, mango and orange juices are Rs. 20 per bottle,Rs.40 per bottle and Rs.50 per bottle, respectively,. The TU schedule of Vinod is given below: Vinod has a monthly income of Rs.340. Being an addict to fruit juices, he spends all his income on Apple, Mango, and orange juices. The prevailing prices of apple, mango and orange juices are Rs. 20 per bottle,Rs.40 per bottle and Rs.50 per bottle, respectively,. The TU schedule of Vinod is given below: Bottles consumed TU of apple TU of juice Mango juice TU of orange juice 1 140 170 320 2 260 330 580 3 340 420 820 4 410 500 1020 5 460 570 1180 6 500 630 1300 7 520 670 1360 Capital TP AP MP 1 10 4 4 4 2 10 10 5 6 3 10 21 7 11 4 10 40 10 19 5 10 55 11 15 6 10 60 10 5 7 10 63 9 3 8 10 64 8 1 9 10 63 7 -1 Identify the three stages of production. • Marginal product schedule of a firm at various levels of inputs is given below: No. of units • • • 1 2 3 4 5 6 Labour 144 96 60 48 36 24 Capital 120 84 60 30 20 10 The wage rate is Rs.12 and cost of capital is Rs.6. If budget of the firm is Rs.60, what is the optimum labor and capital to be employed by the firm? The following schedule shows the total,average and marginal productivity of labour. The wage per unit of labor is constant at Rs.600. L 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 TPl 200 600 1400 2000 2400 2600 2700 APl 200 300 466 500 480 434 385 MPl 200 400 800 600 400 200 100 If the firm produces 2400 units of output what is the average variable cost of production. • During the last period, the sum of profit and FC for a firm totaled Rs. 100,000. Units sold were 10,000. If VC per unit is Rs.4, SP is Rs. 14, what is the profit change if the firm sells 11,000 units of output? • Hint: chg in profit= chg in quantityx (P-AVC) • A firm in a perfectly competitive industry has the following total cost schedule:\ Output Q Total cost (Rs) 10 110 15 150 20 180 25 225 30 300 35 385 40 480 • The going market price of Q is Rs 17. What is the optimal level of output that this firm should produce> what are the profits at this optimal level of output? Is Rs 17 also the equilibrium price in the long run. • • • The following table shows the demand curve facing a monopolist who produces at a constant marginal cost of a Rs 10. What are the firm’s profit-maximising output and price? What is its profit? What would the equilibrium price and quantity be in a competitive industry? Price Quantity 18 0 16 4 14 8 12 12 10 16 8 20 6 24 4 28 2 32 0 36 • If MR=30,Ed=1.5,what will be the price? • Following is the dales data for motorbikes in Firm Sales India. A 12000 B 21021 C 43102 D 24226 E 921 F 402 Total 101672 • what is the value of Herfindahl index? • Expansion in a production facility is a strategy considered by firms in an oligopolistic market. The situation faced by two firms is as follows: Firm 2 Firm 1 Expand Do not expand Expand 8,8 20,0 Do not expand 0,20 10,10 • Does either firm have a dominant strategy?