Eco120Int_Lecture1

advertisement

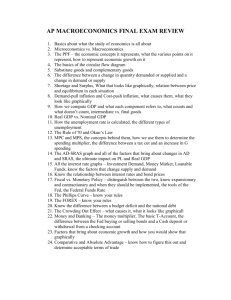

ECO 120 Macroeconomics Week 1 Introduction to Macroeconomics Lecturer Dr. Rod Duncan Topics • • • • • Basic information about the subject A definition of macroeconomics Macroeconomic modelling as storytelling The big questions of macroeconomics Some important macroeconomics variables Some details • Lecturer: Roderick Duncan Email: rduncan@csu.edu.au (preferred) Phone: (02) 6338-4982 Office: C2 - G20 • Class webpage: http://athene.riv.csu.edu.au/~rduncan/Teaching/ Eco120/Eco120.htm Webpage • Webpage – The webpage will hold all the materials for the class, except for some readings available at the Library Reserve. • Lecture Notes (available on Friday before the class) and Tutorial Materials • Hand-outs (available when used) • Review notes (from last semester’s DE subject) • Links for reading/research • Any important notices Lectures and tutorials • Lecture – Lecture notes available on the class webpage • Tutorials – Tutorial papers due for the last 12 tutorials – Tutorial papers available on webpage and through tutors – Only highest 10 marks from tutorial papers count towards final grade Tutorial sign-ups • Tutorial sign-up: – Tutorial sign-up sheets will be handed out during the first class and also available outside C2-232. – Each tutorial is limited to 20 slots. Please fill out your first 5 preferences (from most preferred to least). – The tutorial sheets will be put up outside C2232 on Monday in the second week. Textbook • Textbook – The recommended textbook is Jackson and McIver Macroeconomics. – Earlier editions of Jackson and McIver are fine, just be sure that the topic selection is the same. – Alternative textbooks: There are dozens of first year macro books. Find a second-hand copy or a library copy of another textbook. Just be sure that coverage of the topics is the same. Learning philosophy • Subject learning philosophy and expectations of students – First year is a transition year between high schooltype work and university-type work. – The design of this class is one of continuous assessment- small chunks of work due at regular intervals. – Tutorial papers are collected each week and count for 20% of the final grade. – One mid-term during the semester that counts for 15% of final grade. Learning philosophy • “I hear, I forget; I see, I understand; I do, I remember.” • The only way to learn economics is to do economic problems. • When you get to the final exam, you have to be very good with solving the types of problems that are on the exam- you need to practice, practice, practice. • There is a sample exam in the outline and two sample mid-terms on the website. Assessment • Four assessment items: 1. Tutorial papers- due each week- 10 top grades used- 20% of final grade 2. Mid-term- in second hour of August 29 lecture- 15% of final grade 3. Report- due in tutorial in the 11th week- the week of October 31- 15% of final grade 4. Final exam- during finals week- 50% of final grade and must pass to pass subject. Grade Distribution in Eco120- Spring 05 60 50 Number of students 40 30 20 10 0 HD DI CR PS FL/FW Help with economics • HELP! If you find yourself lost and/or confused, what to do? – Read the Subject Outline. – Check the website. – Email Rod at rduncan@csu.edu.au – Talk to Student Services at http://www.csu.edu.au/division/studserv/ (after all, that’s what they are there for) What is macroeconomics? • Microeconomics- the study of individual decision-making – “Should I go to college or find a job?” – “Should I rob this bank?” – “Why are there so many brands of margarine?” • Macroeconomics- the study of the behaviour of large-scale economic variables – “What determines output in an economy?” – “What happens when the interest rate rises?” Teaching goals • What is it that students should gain from a macroeconomics class? 1. Definitions of important economics terms – Economics is a language. To speak it, you must have a vocabulary. 2. Ability to use macroeconomics to talk about the real world (story-telling) – Explanation: use macroeconomics to explain the past. – Prediction: use macroeconomics to predict the future. Economics as story-telling • In a story, we have X happens, then Y happens, then Z happens. • In an economic story or model, we have X happens which causes Y to happen which causes Z to happen. • There is still a sequence and a flow of events, but the causation is stricter in economic story-telling. Gorgeous, the shih tzu puppy Two uses of a story/model • Puppies get bored easily and, unless watched, will tear things up. • We have two variables: Parental supervision and puppy destruction. A model simply represents the relation ship between 2 or more variables. (Not a very good) Model: Parental supervision↑ → Destruction↓ • Explanation: “My socks are all over the living room because I was not watching the puppy.” • Prediction: “If I watch Gorgeous, she won’t get hold of any socks.” Elements of a good story • All stories have three parts 1. Beginning- description of how things are initially- the initial equilibrium. 2. Middle- we have a shock to the system, and we have some process to get us to a new equilibrium. 3. End- description of how things are at the new final equilibrium- the story stops. • “Equilibrium”- a system at rest. Timeframes in economics • In economics we also talk in terms of three timeframes: – “short run”- the period just after a shock has occurred where a temporary equilibrium holds. – “medium run”- the period during which some process is pushing the economy to a new long run equilibrium. – “long run”- the economy is now in a permanent equilibrium and stays there until a new shock occurs. • You have to have a solid understanding of the equilibrium and the dynamic process of a model. What are the big questions? • What drives people to study macroeconomics? They want solutions to problems such as: – Can we avoid fluctuations in the economy? – How can we make the economy grow faster? – Can we lower the unemployment rate? – Why do we have inflation? – How can we manage interest rates? – Is the foreign trade deficit a problem? Economic output • Gross domestic product- The total market value of all final goods and services produced in a period (usually the year). – “Market value”- so we use the prices in markets to value things – “Final”- we only value goods in their final form (so we don’t count sales of milk to cheesemakers) – “Goods and services”- both count as output Nominal versus real GDP • We use prices to value output in calculating GDP, but prices change all the time. And over time, the average level of prices generally has risen (inflation). – Nominal GDP: value of output at current prices – Real GDP: value of output at some fixed set of prices Measuring GDP • Are we 40 times (655/16) better off than our grandparents? – Australian GDP in 1960- $15.6 billion – Australian GDP in 2000- $655.6 billion • What are we forgetting to adjust for? Measuring GDP • Population- Australia’s population was 10 million in 1960 and 19 million in 2000. – GDP per person in 1960 = $15.6 bn / 10m = $1,560 – GDP per person in 2000 = $655.6 bn / 19m = $34,500 • Prices- $1,000 in 1960 bought a better lifestyle than $1,000 in 2000. Nominal versus real GDP • So how to correct for rising prices over time? – Measure average prices over time (GDP deflator, Consumer Price Index, Producer Price Index, etc) – Deflate nominal GDP by the average level of prices to find real GDP Real GDP = Nominal GDP / GDP Deflator Some Australian economic history Australian GDP 1950-1995 600 000 500 000 Million A$ 400 000 GDP 300 000 GDP Change Real GDP 200 000 100 000 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Measuring GDP • Real GDP -If we instead use 1996-1997 prices to calculate GDP then Australia GDP in 1960 was $138 billion while Australian GDP in 2000 was $631 billion. • Real GDP per person – 1960: $138bn/10m = $13,800 – 2000: $631bn/19m = $33,200 • So we are 2.5 times better off than our grandparents. Business cycle • The economy goes through fluctuations over time. This movement over time is called the “business cycle”. – Recession: The time over which the economy is shrinking or growing slower than trend – Recovery: The time over which the economy is growing more quickly than trend – Peak: A temporary maximum in economic activity – Trough: A temporary minimum in economic activity. Australian business cycle Aust Business Cycle 10 8 6 4 % Ch RGDP 2 0 1950 -2 -4 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Two sides of macroeconomics • Short-term fluctuations- business cycle – Concerned only with short-term changes in GDP due to shocks to the economy – Covered by various models like the Aggregate Demand-Aggregate Supply model – Questions: What impact will a rise in interest rates have on the economy? • Long-term changes- economic growth – Concerned with long-term evolution of GDP over time – Covered by various models such as the Solow growth model – Questions: Why are Australians paid 10 times what Indonesians are paid? Unemployment • To be officially counted as “unemployed”, you must: – Not currently have a job; and – Be actively looking for a job • “Labour force”- the number of people employed plus those unemployed • “Unemployment rate” – (Number of unemployed)/(Labour force) Unemployment • Working age population = Labour force + Not in labour force • Labour force = Employed + Unemployed Unemployment Unemployment over the Business Cycle 12 10 Percent (%) 8 6 Unemployment 4 Change in GDP 2 0 1965 1968 1971 1974 1977 1980 1983 1986 1989 1992 1995 -2 -4 Inflation • Inflation is the rate of growth of the average price level over time. • But how do we arrive at an “average price level”? – The Consumer Price Index surveys consumers and derives an average level of prices based on the importance of goods for consumers, ie. a change in the price of housing matters a lot, but a change in the price of Tim Tams does not. Consumer Price Index • Then the CPI expresses average prices each year relative to a reference year, which is a CPI of 100. CPIt = (Average prices in year t)/(Average prices in reference year) x 100 • Inflation can then be measured as the growth in CPI from the year before: – Inflationt = (CPIt – CPIt-1) / CPIt-1 2.0 0.0 -2.0 Sep-04 Sep-02 Sep-00 Sep-98 Sep-96 Sep-94 Sep-92 Sep-90 Sep-88 Sep-86 Sep-84 Sep-82 Sep-80 Sep-78 Sep-76 Sep-74 Sep-72 Sep-70 Inflation Consumer Price Inflation 20.0 18.0 16.0 14.0 12.0 10.0 8.0 6.0 4.0 Inflation Interest rates • The Reserve Bank of Australia manages Australian interest rates. • The management of interest rates is one aspect of what is called “monetary policy”. • All interest rates (whether home loan rates, business interest rates, RBA cash rates) all move together, so we commonly just refer to “interest rates fell”. Interest Rates 18.00 16.00 14.00 12.00 10.00 Bank Interest Rates 8.00 6.00 4.00 2.00 Jan-03 Jan-00 Jan-97 Jan-94 Jan-91 Jan-88 Jan-85 Jan-82 Jan-79 Jan-76 Jan-73 Jan-70 0.00 Balance of payments •Current account of a country’s international transaction refers to the record of receipts from the sale of goods and services to foreigners (exports), the payments for goods and services bought from foreigners (imports), and also property income (such as interest and profits) and current transfers (such as gifts) received from and paid to foreigners. •Capital account is a summary of country’s asset transactions with the rest of the world, such as sales of Australian property to foreigners and Australian purchases of foreign properties. Current Account Deficits (19491996) 4000 5 2000 0 19 49 19 51 19 53 19 55 19 57 19 59 19 61 19 63 19 65 19 67 19 69 19 71 19 73 19 75 19 77 19 79 19 81 19 83 19 85 19 87 19 89 19 91 19 93 19 95 -2000 0 -4000 -6000 -5 -10000 % of GDP Millions A$ -8000 -12000 -14000 -16000 % of GDP -10 -18000 -20000 -22000 -15 -24000 -26000 -28000 -30000 In A$ -20