What are wrongful death lawsuits?

advertisement

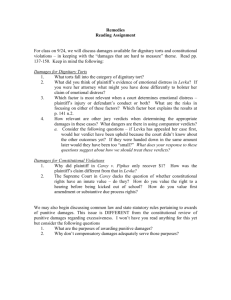

Goals of Punitive Damages • Punishment • Notions of public morality and “just deserts” require that Ds “pay” for their bad actions • Deterrence • Compensatory damages, criminal sanctions and/or government safety standards don’t sufficiently deter the conduct at issue so punitive damages are necessary. • Focus is on D’s behavior not P’s losses Why don’t compensatory damages, criminal fines, safety standards sufficiently deter/punish? • Difficulty of measuring some damages may cause under compensation & under deterrence • Some wrongs are small but nevertheless outrageous (damage awards may not deter) • E.g., Levka – strip search of all female arrestees • Some behavior is extremely profitable (beyond awards of compensatory damages) • Some Ds profit in ways that compensatory damages can’t account for – i.e., pleasure at causing another pain • Criminal fines are usually quite small (even smaller than compensatory awards) • Safety standards are often not enforced by administrative officials & fines are often small Jury Instructions/Judicial Review Regarding Punitive Damages • Courts have recognized legitimacy of punitive damages for centuries. But such damages sit uneasily within the notion of civil compensation. So courts have also attempted to ensure that they are awarded only • as a result of the worst conduct; • not grossly excessive or a result of bias or prejudice toward the defendant. • Possible approaches to controlling punitive damage awards (usually seen in jury instructions and/or judicial standards governing post-verdict judicial review) ▫ Epithet approach ▫ Factors approach ▫ Multipliers (as instituted by SCT in Exxon) Epithets Approach • Jury is given an instruction to award punitive damages if the jurors believe defendant’s behavior was “willful and wanton” or “outrageous” – or some such behavior. • Any award of punitive damages will be subject to judicial review: • Could be a standard as vague as the standard for “remittitur” – are the damages grossly excessive? • Could be subject to review based on factors – see slide 6 • Could be subject to review based on a statutorily prescribed approach • How does Exxon multipliers approach fit in? Jury instruction using a typical “epithet” approach: • Missouri’s standard for awarding punitive damages: • D's conduct must be outrageous because of “evil motive or reckless indifference.” ▫ Intentional tort • Jury instruction (MAI 10.01) – “If you believe D’s conduct was outrageous because of evil motive or reckless indifference to the rights of others” in addition to compensatory damages “you may award plaintiff an additional amount as punitive damages in such sum as you believe will serve to punish defendant and to deter defendant and others from like conduct.” ▫ Recklessness Jury Instruction (MAI 10.02) – “If you believe D’s conduct shows complete indifference to or conscious disregard for the safety of others” in addition to compensatory damages “you may award plaintiff an additional amount as punitive damages in such sum as you believe will serve to punish defendant and to deter defendant and others from like conduct.” • If the jury in Exxon were instructed under an epithets approach, how would Exxon fare? What did Exxon do? Is it, should it be, responsible for Hazelwood? Jury instruction or review using a “factors” approach • Some states have juries consider various factors to determine whether punitive damages should be awarded. Other states have judges use these factors to review jury awards based on an epithets approach. • Such factors can include: ▫ Actual/likely harm from D’s conduct ▫ Reprehensibility of D’s conduct ▫ Profitability of D’s conduct ▫ Financial condition of D ▫ Amount of compensatory damages ▫ Other possible criminal or civil penalties for D’s conduct • Are these factors relevant? Prejudicial? Distracting? • Is this approach better than the “epithet” approach? • Would Exxon fare differently under this approach than under the epithet approach? Exxon – The SCT’s multipliers approach • Unlike the “epithet” or “factors” approach, Exxon SCT used a “multipliers” approach to review the punitive damages award. • So far, this approach ONLY applies in federal courts when they act as common law courts (i.e., maritime cases). It does NOT supplant particular state court approaches unless state courts adopt it. ▫ Why does the SCT use this approach? ▫ Why does SCT use a 1:1 ratio as the appropriate ratio rather than some of the higher ratios seen in legislation (i.e., 3:1, 5:1)? SCT says that a 1:1 ratio is appropriate only for “this particular type of case” – what type of case is that? When would a different ratio be appropriate? ▫ Should courts be in the position of imposing ratios as opposed to legislatures? Ways for courts to limit awards (at common law) o Judicial Review Using Factors – judges use factors to review verdicts for excessiveness o Remittitur – review to see if damages are grossly excessive o Higher standard of proof – majority of states require “clear & convincing proof” of D’s mental state before imposing punitive damages o Missouri – Rodriguez v. Suzuki Motor Corp (1996) o Higher threshold for respondeat superior liability – Half the states require managerial employees to be implicated in decisions while half allow punitives with ordinary respondeat superior liability o Missouri appears to be an ordinary respondeat superior state o Restricting awards in multiple victim cases – Should all victims in mass tort cases get punitive damages or only the first to sue? Courts generally reject the latter approach preferring to take possible other awards into account when setting the amount of punitives Legislative approaches to limiting punitive damages o Caps on damage awards o o Bifurcated trial o o Mo. Rev. Stat. §510.263 – post trial motion allows D to prove up punitive damages paid arising out of the same conduct. If successful, D gets credit on any punitive damages awarded in this trial Defendant only severally liable o o Mo. Rev. Stat. §510.263 – parties can request bifurcated trial. No evidence of D’s wealth admissible at liability stage. Credit for punitive damages previously paid o o Mo. Rev. Stat. §510.265 – limit awards to $500,000 or 5x net compensatory damage award, whichever is greater Mo. Rev. Stat. §537.067 – D less than 51% at fault is only severally liable for percentage of punitive damages for which D at fault Pay portion of punitive damages to the state o Mo. Rev. Stat. §537.675 – State has lien on 50% of all final judgments awarding punitive damages, which it deposits in tort victims fund Constitutional challenges to punitive damages o In addition to common law review of punitive damages, SCT has entertained constitutional challenges to punitive damage awards o Typical constitutional challenges o Excessive Fines – 8th Amendment o Browning v. Kelco Disposal (1989) – SCT rejected the argument because 8th Amdt requires fines payable to the state and punitives are payable to individual defendants o Procedural Due Process – 14th Amendment o Pac. Mutual Life v. Haslip (1991), Honda Motor Co. v Oberg (1994) – Constitution requires adequate procedural safeguards when awarding punitive damages o Substantive Due Process – 14th Amendment o TXO Production Corp. v. Alliance Resources Corp. (1993), BMW v. Gore (1996), State Farm v. Campbell (2003) – Constitution provides a substantive right against excessive punitive damage awards Why does it matter whether court reviews excessiveness of punitive damages from common law or constitutional perspective? Common Law Review D moves to set aside verdict due to excessiveness based on common law. Reviewing court uses “abuse of discretion” standard to review judge’s ruling on this motion If remittitur granted – P given option of new trial when damages remitted. Constitutional Review D makes motion to set aside verdict due to excessiveness based on constitution. Reviewing court uses “de novo” standard to review jury verdict If remittitur granted – P (theoretically) must take remitted damages (unless further appeals are available). But sometimes courts offer new trials. o Possibility of SCOTUS review of state court tort judgments; federal courts can apply own standards in diversity cases (since the case involves a constitutional issue)