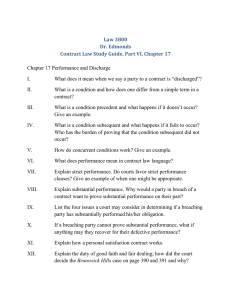

Section 4 Guide to Compeition Law

advertisement

Section 6 Modern Competition Rules - Guide Australia Europe Japan Malaysia New Zealand Philippine United States of America • Understand and meet external and internal customers’ needs. • Work with customers to create solutions. • Always honour our commitments. • Consistently provide the best quality products and services. • Allow decisions to be made as close as possible to our customers. Competition law has been has been part of the business scene for a very long. It was part of the common law when Britain laid claim to New Zealand in 1840; it became part of the statute law with the passing of the Commerce Act (the Act) in 1906. The competition Rules are primarily enforced by the Commerce Commission. There are circumstances where both the Commerce Commission can bring enforcement proceedings and an injured firm (including a natural person) can bring a claim for injunctive relief, damages and corrective advertising. The Commerce Act protects competition - not competitors The Australian High Court, when considering the Australian equivalent of the Commerce Act, made this point clear in the Queensland Wire case when it said: The object is to protect the interest of consumers, the operation of the section being predicated on the assumption that competition is a means to that end. Competition by its very nature is deliberate and ruthless. Competitors jockey for sales, the more effective competitors injuring the less effective by taking sales away. Competitors almost always try to ‘injure’ each other in this way. This competition has never been a tort; these injuries are an inevitable consequence of the competition the rule is designed to foster. Competition law lays down rules by which we compete – the so-called Competition Rules. The competition Rules apply to: 1. Contracts, arrangements and understandings Rule 1 bars those that have a: • • • purpose, effect or likely effect, or potential effect of substantially lessening (including preventing or hindering) competition purpose, effect or likely effect, of price influencing (fixing) or purpose of boycotting. Rule 2 bars the use of a substantial degree of market power with a purpose of damaging a competitor, deterring a competitor from competing, or discouraging a ‘new entrant’ from entering a market. 2. Practices Rules 3 and 4 bar practices that constitute: exclusive dealing, for example: o ties (i.e. vertical distribution arrangements) that have a purpose, effect or likely effect of substantial lessening of competition; o third line forcing; and o re-sale price maintenance. resale price maintenance Who do the rules apply to? • • The competition Rules apply to all persons and corporations who engage in trade or commerce. As such they can apply to individuals, you should assume the competition Rules apply to you. It is a breach of the Act to break a competition Rule. It is also a breach for any person to: aid, abet, counsel, procure or induce, directly or indirectly; be knowingly concerned in, or a party to conspire with others to or effect a breach of the competition Rules. Non-compliance • • • • Failure to comply with the competition Rules can result in a breach of the Act and legal action can be taken by the Commission. If the company or an individual is found guilty of an offence under the Act this will result in the imposition of ‘fines’, awards of damages, grants of injunction and orders to pay costs. A firm cannot pay a ‘fine’ imposed on an employee. Where a breach damages a firm, that firm can bring a private action for damages. Under the Act an employee can be personally liable for a fine imposed by the Commission as a result of a breach of the act. The Act also prohibits a company from paying a fine imposed on an employee. Finally, where a company has been damaged by a breach of the Act, the company has the right to sue for damages it has suffered by the breach. Understanding the Rules First – Understanding the key words and concepts in the competition rules The competition Rules bar those contracts, arrangements, understandings, uses and practices that: • • do, or might, result in a substantial lessening (including preventing and hindering) of competition in a market; or result in price influencing, boycotts, misuse (abuse) of market power, third line forcing or resale price maintenance. Determining when competition has been substantially lessened and which firms have market power requires a basic understanding of economic concepts such as competition, market and substantial. Competition Competition takes place when two or more firms go after the same business at the same time. It occurs in a market. Market Market has three main dimensions: • • • products (goods and/or services) – products popularly considered capable of being substituted for each other, whether or not they are; function – the stage in the production and distribution chain at which competition is occurring (i.e. wholesale or retail); and area – the geographic area in which the seller is prepared to deliver products. The market is the area of overlap of product, function and area considered within a single time frame. Purpose and effect Purpose is what is wanted to be achieved. It: • • • • • • is the actual intention ; must be a substantial purpose ; need not be the only purpose ; need not have been achieved ; is to be distinguished from consequence; and is determined with reference to the time of the action being considered (i.e. with hindsight). Purpose is either: • • directly evident (e.g. admissions in documents); or inferred from acts done, matters written and words said that can’t be justified on the basis of a rational alternative permissible explanation. In the absence of direct evidence of a prohibited purpose, the courts will look far and wide for acts done, matters written and words said that support the inference that there is a prohibited purpose. An absence of a rational commercial basis for those actions leaves it wide open for the Commission (and a court) to infer a prohibited purpose. Effect is the result or consequence of an act or omission. Likely effect is just that, the likely effect of an act or omission. For present purposes, the term likely effect is taken to include actual effect. Substantial is used in different contexts; it’s meaning is taken from the context in which it is used. • • In the context of a substantial lessening of competition - Rules 1 and 3 (i.e. contracts, arrangements, understandings and practices), it is used in a relative sense. It is measured by reference to the actual and potential competitors in the relevant market. It signifies ‘real’, ‘of substance’ or ‘of significance’ In the context of a misuse of substantial degree of market power - Rule 2 (i.e. uses), it signifies ‘large or weighty’ or ‘considerable, solid or big’. Substantial lessening of competition Where there is effective competition, no seller has the power to choose its level of profit by giving less and charging more. Competitors (whether existing competitors or potential new entrants) keep this power in check. A hallmark of effective competition is the flexibility to respond to competitors’ initiatives by making adjustments to any of the tactics used to keep and win business (i.e. price, trading terms, technology, quality, consistency and support). Factors relevant to measuring impacts on competition include: • • barriers to entry. Matters considered when measuring the barriers include: o financial capabilities (i.e. economies of scale and the size of sunk costs if an entrant is unsuccessful); o natural hurdles (i.e. access to raw materials and essential facilities); o legal or institutional constraints (i.e. tariffs, regulatory protection); and o extent of excess capacity of existing competitors. constraints exerted by existing competitors. Matters to be considered include: o intellectual property rights (i.e. patents and licenses) o extent of vertical integration ; o extent of product differentiation (i.e. brand loyalties) and (iv) extent of concentration of competitors in the market. The test is subjective and, at the end of the day, applied by a judge after reviewing all the evidence. Market power Market power is the ability to behave persistently different from a competitor. Most cases dealing with market power refer to the ability to increase price without regard to competitors’ probable response. The exercise of market power is not limited to pricing; it manifests in other areas such as the power to: • • select a product range to resell without reference to the desires of the consumers; or increase terms of trade without regard to competitors’ probable response. Tools used to show that the competition rules have been breached The Commission has wide powers to seek out evidence of breaches of the competition Rules. Those powers include the right to enter premises (home or office) and take records and ask questions. Refusal to produce documents or answer questions can lead to penalties being imposed. Often the available evidence that points to a breach of the competition Rules is incomplete. Those that breach the law sometimes try to conceal the evidence. The courts can be called upon to decide if there has been a breach on the basis of the inferences open to be drawn from the evidence that is available – fill in the blanks! Fines (proposed) Maximum fines for a breach of the competition Rules • • involving cartel behavior by a: o company – the maximum penalty – greater of: $10 million , three times the gain from the contravention or , where gain cannot be readily ascertained, 10 per cent of turnover and forfeiture/disgorge any compensation. o person 7 Years in prison. not involving cartel behavior o by a company – the maximum penalty – greater of: $10 million (ii) three times the gain from the contravention or ( where gain cannot be readily ascertained, 10 per cent of turnover and forfeiture/disgorge any compensation. o person – a maximum of $500,000 Case Law But how much? The messages delivered by judges on the appropriate size of a penalty are very clear! Judge French, in the CSR case stated: The object of penalties: put a price on a contravention that’s sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene”. Justice Merkel, in a number of Victorian petrol retailers’ cases stated: The need: impose penalties that constitute a general deterrence to others disposed to engage in similar conduct”. He went on: If any lesson is to be learned it should be that the best protection against contraventions and penalties arising from anti-competitive conduct is the elementary step of ensuring that directors and employees are educated and properly instructed about anti-competitive conduct. The failure to do so can be a very costly exercise for those involved in such contraventions”. RULE 1 • Always work safely and follow rules and procedures already in place. • Systematically identify, understand and control risk. • Strive to continuously reduce impacts on the environment. • Take pride in creating a better workplace. • Set high standards and lead by example. We can talk to the market but not to our competitors We are allowed to: • tell everyone (i.e. competitors and customers) in the market what we are about to do (i.e. changes to our prices, trading terms, product range or preferred customer base). That gives us first mover advantage and leaves everyone else in the market with a decision as to how to react – their reactions are competition at work. We are NOT allowed to: • • tell our competitors ahead of telling the market what we are about to do; or set about substantially lessening competitive tension by reaching accords with others in the market. Always take advice when a: • • competitor tells you what it is about to do ; or competitor’s response to our marketing initiatives becomes predictable Overview Never: • • communicate with competitors with a o purpose to boycott; or o purpose of, or where the likely effect is price ‘influencing’; or communicate with anyone with a purpose of, or where o the likely effect is, substantially to lessen competition. Rule 1 applies to all contracts, arrangements and understandings but not all will breach the Rule. The Rule is breached: • • by making a contract or arrangement or arriving at an understanding and again by giving effect to it, if; o the parties (who need not be competitors) or any of them had a purpose of substantially lessening competition; or o the likely effect was to substantially lessening competition or if two or more (but not all) are competitors and has: a purpose of price influencing or boycotting or the likely effect, of price influencing. Key to the operation of rule 1 is a contract, arrangement or understanding containing a provision that has a purpose or effect of substantially lessening competition, or establishing a boycott. Purpose is what is intended will be achieved. Effect is what is achieved. Likely effect is what might be achieved. Substantial is used in a relative sense and signifies ‘real’, ‘of substance’ or ‘of significance’. Boycotts can be either exclusionary or secondary; they operate to limit the supply or acquisition of products. In the case of: exclusionary boycotts, the limitation is on one or more of the parties; and secondary boycotts, limitation is on a non-party. Boycotts and price influencing are excluded from Rule 1 if they: are between a parent company and its subsidiaries or between a parent company’s subsidiaries; or constitute the practice of exclusive dealing, in which case it will be dealt with under Rule 3, or the practice of re-sale price maintenance, in which case it will be dealt with under Rule 4. Boycotts (exclusionary) and price influencing breach the Rule irrespective of the effect on competition where two or more parties to the underlying contract, arrangement or understanding are actual or potential competitors. Rule 1 All contracts, arrangements and understandings fall for consideration under Rule 1. Contracts, arrangements and understandings that breach Rule 1 because they contain a cartel provision are treated more seriously than those that don’t. A cartel provision is one that: involves price influencing; restriction on outputs in the production or supply chain; allocation of customers, suppliers or territories; and bid rigging. What are contracts, arrangements and understandings? A contract is a legally binding relationship: • with two or more parties ; with each party having defined rights and obligations; • • recorded in writing, made orally, or simply implied from he conduct of the parties; and that is enforceable through the courts. An arrangement is a morally binding relationship: • • with two or more parties ; with each creating in the other an expectation that it will act in a certain way; and that is not legally binding. An understanding is arrived at when two or more people learn of what one of them intends to do. In the Adelaide Beer case a judge observed that: "... it seems that one could have an understanding between two or more persons restricted to the conduct which one of them will pursue without any element of mutual obligation, insofar as the other party or parties are concerned." Consider: if you learn what another is to do (e.g. in a conversation or by reading its advertisement) you have an understanding. You may not have a contract or an arrangement but, at the very least, you have an understanding – you understand what that other is to do In summary, all communications fall for consideration under Rule 1. Contracts, arrangements and understandings only breach Rule 1 if they have: a purpose of: o substantially lessening competition; o price influencing ; or o boycotting the likely effect, of: o substantially lessening competition; or o price influencing. It is a further breach of the Rule to give effect to a contract, arrangement or understanding that breached the Rule when made or arrived at. All of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding are in breach – not just the ringleader. Excluded from the ambit of Rule 1 are communications between a parent company and any or all of its subsidiaries and between those subsidiaries. No other communication is excluded. Purpose and effect. Rule 1 is triggered by purpose or effect. Purpose is what is intended be achieved. Keeping in mind that it can be either expressed or inferred, consider the actions of a competitor about to increase its prices. If it communicates the detail of the planned price increase to you (and you are not a customer for the goods the subject of the communication) it is almost certain that a court will infer the purpose is to influence your firm’s prices, Rule 1 will be breached. What purpose can be inferred in each of the following scenarios? Your competitor: (a) telephones you and tells you and no one else of the planned price increase (b) uses only one billboard – the one located opposite your office – to advertise a planned price increase and (c) advertises a planned price increase in a full-page advertisement in a mass circulation newspaper. In the case of the telephone call and the billboard, you, not the market, are the focus of the communication. It is almost certain that the purpose is to influence your firm’s prices. In the case of the newspaper, the communication is to the market. The apparent purpose is to inform the market with nothing else to suggest that the purpose was to influence price - you are allowed to talk in an open market Determining if competition has been substantially lessened in a relevant market Substantial in Rule 1 is used in a relative sense. It is measured on the basis of the actual and potential impact the contract, arrangement or understanding has on competition in relevant markets. Here the cases talk in terms of ‘real’, ‘of substance’ or ‘of significance’ - see section on key words and concepts. Relevant markets are those in which any party to the contract, arrangement or understanding deals, is likely to deal or, but for the contract, arrangement or understanding, would be likely to deal. The market is defined by reference to: products that are in practical terms interchangeable; the geographic area targeted by suppliers. Keep in mind that the movement of commerce to the internet will drive change to the market; and the functional level (i.e. wholesale or retail) Provisions in a contract, arrangement or understanding that are price influencing or boycotting will be deemed to substantially lessen competition Price influencing involving competitors is prohibited Price influencing occurs where a contract, arrangement or understanding has; several parties of which at least two are competitors; and a purpose or likely effect of influencing the price for, or a discount, allowance, rebate or credit in relation to products which any of those parties acquires or supplies. Price influencing is generally deemed to lessen competition substantially. The rule is deemed not to be breached where the price influencing involves: products supplied by joint venturers; or joint buying and advertising schemes. In these cases, the rule will be breached only if there is, or is likely to be, a substantial lessening of competition. Boycotting is prohibited Boycotts can be exclusionary or secondary. Exclusionary boycotts occur where a contract, arrangement or understanding has: two or more parties (1 and 2 in the diagram) that are competitors; and a purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting any of the parties (or their related corporations) from dealing with particular: o persons or class of persons ; o persons in particular circumstances; or o persons on particular conditions Firms are considered to be competitors if they would, but for the contract, arrangement or understanding, be likely to compete. Boycotts that are based on a cartel provision of a contract, arrangement or understanding that have as parties tat least two competitors are dealt with harshly. A cartel provision is one that do or are likely to result in: price influencing (i.e. fixing, controlling or maintaining) in respect of either the supply or acquisition of goods and/or services; restrictions on outputs in the production or supply chain; allocation of customers, suppliers or territories; or bid rigging where some of the parties agree: o not to bid; o submit less competitive bids; o withdraw from the bidding process; o proceed with their bids but in a manner that favours other bidders; and o on a material component of the bid in advance. Examples of exclusionary boycotts are: (a) a supplier’s customers agreeing not to deal with the supplier if it supplies a specified new customer (b) manufacturers of a product agreeing that each will sell its product only on a supply-and-install basis (c) a supplier sharing with a competitor credit information about a customer with the intention that the competitor will not open an account for the customer until the customer has paid his account with the supplier and (d) distributors as a group agreeing with the manufacturer on their marketing territories. A secondary boycott occurs when the parties (1 and 2 in the diagram) act in concert to: (a) hinder or prevent another (3 in the diagram) from selling products to, or acquiring products from, another (the target – 4 in the diagram) if a purpose or likely effect is to: (i) cause substantial harm to the target or (ii) substantially lessen or hinder competition in a market in which the target sells or acquires products or (b) prevent or substantially hinder the target from engaging The prohibition against a secondary boycott does not apply where: (a) the parties includes an employee of the target or (b) one of the parties is an employee of a third person or (c) the dominant purpose was to preserve or further its business; or (d) the dominant purpose is substantially related to: (i) remuneration, conditions of employment, hours of work or working conditions of the parties or (ii) environmental protection or consumer protection but is not done by way of industrial action. A union and its members are presumed to act pursuant to a contract, arrangement or understanding. The onus is on the union to rebut that presumption. If it fails to discharge the onus, the union will be liable for loss or damages suffered as a result of any boycotts implemented by its members. All agreements with unions are prohibited where the purpose is to prevent or hinder trade between a party to the agreement and another entity. Boycotts and price influencing do not breach Rule 1 where the underlying contract, arrangement or understanding: (a) is between a parent and any or all of its subsidiaries or between some or all of its subsidiaries (b) constitutes exclusive dealing (Rule 3) (c) constitutes re-sale price maintenance (Rule 4) (d) provides for the acquisition of assets or shares in a company or (e) is conditional on a grant of authorisation by the Commission Rule 2: Intentional misuse of substantial degree of market power • Do what we say we will. • Listen, understand and engage new ideas. • Harness the talents of those we work with, to achieve the best outcomes. • Passionately promote and protect our company reputation. • Treat people with respect, and challenge those who don’t. We can grow our business We are allowed to: • win business by being better than our competitors. Winning business is competition at work. We are not allowed to: • target for demolition or injury the business of another. Always take advice when: • a marketing initiative is only possible because of our size or the influence we can bring to bear on suppliers, resellers, competitors or customers. Overview Never use market or pricing powers with the purpose of: eliminating or damaging a competitor; preventing the entry of any firm into any market; or deterring or preventing any firm from engaging in competitive conduct in any market. Rule 2 is concerned with firms that have a: o substantial degree of market power; or o substantial market share that offer to sell product below relevant cost for a sustained period. A breach occurs where that power is used or a below relevant cost offer is made for a sustained period with a prohibited purpose. That is, a purpose to: bar a new entrant; eliminate or damage a competitor; or deter competition (in any market). Steps for rule breaches There are three steps to establish a breach of the rule: Step 1 – show the firm has either a substantial degree of market power or market share. In the context of rule 2, substantial signifies ‘large or weighty’ or ‘considerable, solid or big’; Step 2 – show the firm had a prohibited purpose; and Step 3 – show that the firm either used its substantial degree of market power or, if it had substantial market share, offered product for sale below relevant cost for a sustained period with the intention of achieving the prohibited purpose. Rule 2 is concerned with firms that have a: substantial degree of market power; or substantial market share that offer to sell product below cost for a sustained period. The rule is not concerned with the fact that a firm has substantial market power or market share or how that power or share was gained. A breach occurs where that either the power is used or product is offered for sale below relevant cost for a sustained period with a prohibited purpose. That is, a purpose to: bar a new entrant; eliminate or damage a competitor; or deter competition (in any market). Rule 2 does not operate to: protect a new entrant or small player from robust competition; nor require a firm with a substantial degree of market power or market share to cede business to a new entrant or another competitor. For there to be a breach of rule 2, three steps need to be taken: Step 1 – show the firm has either a substantial degree of market power or substantial market share. A firm has substantial market power where its business is not constrained by competitors, suppliers or customers. It will be substantial when the firm is able to behave without regard to (actual and potential) reactions of competitors, suppliers and customers. Measuring market power is not a precise science. As a guide, a firm will be taken to have a substantial degree of market power when it has the power to impose its will on its competitors, suppliers or customers (e.g. unilateralism manifesting by the refusal to supply, imposition of terms of trade or price increases). More than one firm can have a substantial share of the same market. The courts are yet to decide how big a substantial market share is. It is likely that in the case of a well-resourced firm a substantial share could very possibly be as low, possible as low as 20%. Step 2 – show the firm had a prohibited purpose – that is to: bar a new entrant; eliminate or damage a competitor; or deter competition (in any market). Purpose is what is wanted to be achieved. Earlier, the point was made that, in the absence of direct evidence of a prohibited purpose, the courts will look far and wide for acts done, matters written and words said that support the inference that there is a prohibited purpose. An absence of a rational commercial basis for those actions, leaves it wide open for the Commission (and a court) to infer a prohibited purpose. Consider the position of a duopolist faced with price competition from a new entrant. Would it, by meeting that competition with aggressive pricing of its own, be: pursuing a commercially sound, competitive strategy to maximize profits/minimise losses; or implementing a strategy to damage the new entrant or drive it out of the market? The first is permissible. The second is a breach of rule 2. The challenge is to decide which scenario was applicable. The challenge is met with a search for actions that point to one of the scenarios. Step 3 – show that the firm either used its substantial degree of market power or, if it had a substantial market shares, offered product for sale below relevant cost for a sustained period with the intention of achieving the prohibited purpose. A firm with a substantial degree of market power will, absent evidence to the contrary, generally be regarded as not using that power for a prohibited purpose if: it would be rational for it to act in the same way even if it did not have the power (counterfactual test); or its capability to act in such a way pre-existed its gaining the power. The courts can infer that a firm: has a substantial degree of market power where it, by way of example, adopts below cost pricing with the knowledge that it will later be able to recoup its loss (the greed factor); or is using its substantial degree of market power for the a prohibited purpose where its actions could not be replicated by a firm that did not have a substantial degree of market power Rule 3: Exclusive Dealing – ties & third line forcing • Make decisions and complete tasks to drive profitable business outcomes. • Challenge ourselves to create ways to improve the value of the business. • Focus on the most effective results for our efforts and investment. • Effectively identify and manage business risks. • Recognise that knowledge adds value, and sharing it adds more. We can have a network of suppliers and resellers We are allowed to enter into distribution arrangements with our suppliers and our resellers. We are not allowed to: require a reseller to buy products that can’t be supplied by us from a particular supplier; or limit, where the result is a possible substantial lessening of competition, the right of: o a supplier to supply products to certain other customers or in specified market areas; or o a reseller to: acquire products from our competitors; or resell products we supplied to certain customers or in specified market areas. Always take advice when: limiting the freedom of a supplier or reseller to decide with which firms it does business Overview • Never supply on terms that: oblige a buyer to deal with a particular supplier (third line forcing) or have the purpose, effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition (tie). Exclusive dealing involves one firm trading with another on the condition that it accepts limitations on its freedom to choose with whom, or in what products, it deals. The practice of exclusive dealing can involve either: a vertical restraint (tie), which operates in the supply chain (i.e. supplier to reseller). A tie breaches Rule 3 if it has the purpose or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in a market. Where there are other similar ties operating in the same market the effect is the combined effect of them all and • third line forcing, where a firm supplies products on the condition that the purchaser buys other products from another stipulated supplier or suppliers. For third line forcing to occur, there must be at least two contracts: a ‘primary’ one which arranges supply to a purchaser and a ‘secondary’ one which in some way restricts the purchaser’s trade (including reselling and other purchasing). Third line forcing breaches Rule 3 irrespective of the effect on competition. Exclusive dealing (tie) The practice of exclusive dealing (tie) involves a: (a) supplier limiting its customer’s freedom to: acquire products from competitors of the supplier (or its related corporation) or re-supply the supplier’s products to particular customers; or in particular places, or supply products to particular persons; or in particular places and landlord granting a lease of land or buildings which includes similar restrictions on the tenant to those categories in the first two points. A tie breaches Rule 3 only if it has a purpose or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in a market. In Rule 3 purpose and likely effect are connected to a practice and can be determined at the time any of the first or succeeding acts that together constitute the practice take place. Exclusive dealing (third line forcing – Australia only) Third line forcing is absolutely prohibited; its effect on competition is irrelevant. The four elements of third line forcing are: three parties: two suppliers and a mutual customer; two products ; a condition linking their supply, namely a special price, or the right to get the product or service, from the first supplier; and specification by the first supplier of a particular supplier from whom the second product or service must be obtained. Some examples of third line forcing: a supplier refuses to sell a builder its products on a supply only basis, but requires the builder has them installed by a fixer nominated by the supplier. the supplier’s subsidiary sells land to a developer on the condition that the developer buys from the supplier all his building products needs for the development of the land. Rule 4: Re-sale price maintenance • Work with colleagues to meet our objectives, don’t work in isolation. • Seek to develop ‘win-win’ relationships and avoid ‘win-lose’ relationships. • Work closely with our partners to leverage their knowledge of the construction industry and cement expertise. • Share knowledge with colleagues so that we learn at the fastest possible pace. • Our shareholders have made a major commitment to us, and we need to match this commitment . We can help our resellers We are allowed to give • advice to our resellers We are not allowed to: • leave a reseller with an impression that there: - is a minimum reselling price or - may be adverse consequences if it offers to sell below a particular price Overview Never encourage a reseller to: • • • sell ; offer to sell; or advertise above a particular price. The practice of re-sale price maintenance is a breach of Rule 4. Resale price maintenance relates to goods and/or services in Australia. Re-sale price maintenance occurs where a supplier motivates a reseller to charge above a minimum price when offering to resell the product. Often re-sale price maintenance is enforced through a refusal to supply, but it may also take the form of refusing to grant advertising allowances or discounts. Suppliers should never discourage resellers from advertising, displaying for sale or selling below a specified price. The price will be specified where it is: • • • stated ; determined by reference to the price of another (such as a competitor) for the same or similar goods; or determined, by reference to a formula provided by the supplier or used by another (such as a competitor) in respect of the same or similar goods. • Re-sale price maintenance includes: • • • refusal to supply unless the buyer agrees to resell the goods at a price more than at a specified price refusal to supply because the buyer has sold, or is likely, to sell below a specified price and making a statement as to pricing that is likely to be understood as a minimum price for re-sale. The practice of re-sale price maintenance is a breach of Rule 4. Re-sale price maintenance occurs when a firm: • • • • makes it known to a reseller that it will not supply product unless the reseller agrees not to sell or re-supply below a specified price; induces or attempts to induce, a reseller not to sell or re-supply product below a specified price enters or offers to enter an agreement for the supply of product to a reseller a term of which bars the reseller selling or re-supplying product below a specified price withholds the supply of product to a reseller because the reseller: • has sold or re-supplied the product below a specified price • will not agree not to sell or re-supply the product below a specified price • withholds supply of product for the reason that a second person who has obtained, or wishes to obtain, product from the first person: • has sold or resupplied product below a specified price will not agree not to sell or resupply product below a specified price or using in relation to any product supplied a statement of price which is likely to be understood as the minimum price for that product. A price can be specified by reference to a formula or by reference to another firm’s price. Rule 4 makes no inquiry as to the affect on competition – because it is assumed that preventing price competition in the re-sale market will adversely affect competition. Rule 4 does not: • • apply to commission sales (because there is no reselling and the agent is paid on commission) prevent the setting of maximum re-sale prices. A recommended price is permissible only if it is a non-binding genuine recommendation. The recommended or maximum price must be genuine – the Court may look behind the rhetoric to ensure that the price is not a de facto minimum or reference price. Recommended prices are allowed where the statement of the price: applied to packaging is preceded by the words “recommended price”; or given in any other advice is accompanied by a statement to the following effect: The price set out or referred to herein is a recommended price only and there is no obligation to comply with the recommendation.