dra & dr-ta strategy lessons

advertisement

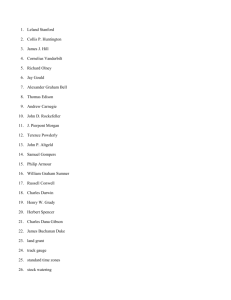

CONTENT LITERACY STRATEGY FORMAT NAME OF STRATEGY: Directed Reading – Thinking Activity ADAPTED FROM: McKenna, M., & Robinson, R. (2009). Teaching through text: Reading and writing in the content areas. p.138-139 CONTENT AREA: Social Studies GRADE LEVEL: 5 TEXTBOOK AND PAGES ADAPTED: Bower, B. , Lobdell, J. (2001) History Alive! America’s Past, Palo Alto, CA: Teacher’s Curriculum Institute, p. 208 OBJECTIVE: I will show that I understand how asking questions can show me the importance of finding out about an event by reading a passage from a history text book answering some questions and asking other questions to understand the importance of what I read. GLE 5.2.1 understands how essential questions define the significance of researching an issue or event. MATERIALS NEEDED: KWL chart, agenda written on large paper. ACADEMIC ENGLISH: goods, products, industries, dramatic, transcontinental, canals, steamboats, factories, offices, quantities, carriages, skyscrapers. Signal words: After, Before, By, The first, Now, More and more. Appositives: Example: During this time, new industries, or businesses, caused such dramatic changes that together they are called a “revolution.” Cause/Effect relationships After the Civil War, the Industrial Revolution changed the way Americans lived and worked. During this time, new industries, or businesses, caused such dramatic changes that together they are called a “revolution.” The first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. Now people and goods could travel across the entire United States in a week. PROCEDURES: 1. Go over agenda: 2. Determine students’ background related to the material to be read: What was the industrial revolution? (Clarify any misconceptions) “Some vocabulary that may be new to some of you is listed here. Take one minute and read the list of words, underlining the words you don’t know. Raise your hand if you have a word you don’t know.” 3. Set purposes for reading. I’ve given you a KWL chart. Can someone explain what that is? It’s a chart with 3 columns- K= what you know, W= what you want to know and L= what you learned. So, first, we’ll talk a little about what you already know, you write it down in the K section of your chart. Then, before and while you read, write in the W section questions you have, what you want to know. Finally, when you finish reading, we’ll talk together, and you record in the L section what you learned. We are going to read a passage about the Industrial Revolution. What do you think they will talk about? In what ways did ways of life change after the Civil War? Did the changes in ways of life last? Do we still use technologies that the old ways changed to? What ways of life are different for us than for our grandparents? (Orient students to each other’s ideas and ask for critique and rationale and record it on the board) - - In what ways did ways of life change after the Civil War? (went from living on farms in the countryside to living in cities, went from working farms to working in city factories, rode horses to driving cars, riding in trains and steam boats, went from making their own necessities to buying premade productos…) Did the changes in ways of life last? Do we still use technologies that the old ways changed to? (Telephones, cars, trains, premade products…) What ways of life are different for us than for our grandparents? (cell phones, cd’s, gps,…) What ways of life are different for us than for our grandparents? ( individual) What would you invent to make our lives better? Why? 4. ( At the end of the passage) Let’s revisit the class predictions- Were you correct? Either way, how do you know? Share examples from the reading. 3. Arrange for students to read silently. I’ve put the passage for reading in the center of the table, along with a KWL chart that goes with the reading. Each of you takes one and begins reading filling in your chart as you go PISL How did asking questions about what you wanted to know, help you learn what you wanted? What did you learn about questions and predicting? What helped you figure out what you wanted to ask? Question Level of Bloom's In what ways did ways of life change after the Civil War? Remembering Did the changes in ways of life last? Do we still use technologies that the old ways changed to? Examples? Applying What ways of life are different for us than for our grandparents? Examples? Analyze What would you invent to make our lives better? Why Creating Purpose for asking/how it is related to objective Did they understand the content of the reading passage/ connect with material in order to begin to understand importance of event Can student use information and connect it to their life? / Understanding importance of event in relation to own life. Can student use information and connect it to their life? / Understanding importance of event in relation to own life. Identifying how questions help connect importance to events. Can student use information and connect it to their life? / Understanding importance of event in relation to own life. Identifying how questions help connect importance to events, and use that knowledge. ASSESSMENT RUBRIC In what ways did ways of life change after the Civil War? Beginning General terms(lived and worked) Approaching 1 specific example of lived and worked changes(from farms to cities, worked on farms to Meeting 2 specific examples of lived and worked changes(from farms to cities, worked on farms to Exceeding More than the two examples and/or extrapolating that candles were the previous method of worked in factories) Did the changes in ways of life last? Do we still use technologies that the old ways changed to? Answer yes Yes, and one example of what change from the Industrial Revolution we still use(phones) What ways of life are different for us than for our grandparents? One example of Two examples how their life is different than their grandparents worked in factories AND made their own things to buying premade products) Yes, and two examples of what change from the Industrial Revolution we still use(phones, cars) Three examples lighting before electric lights. Yes, and three or more examples of what change from the Industrial Revolution we still use(phones, cars, trains) Four examples search index by subject by year biographies books SF Activities shop museum contact Plan for the Pacific Railroad, by Theodore Judah Biography of Theodore Judah The Big Four Driving the Last Spike The greatest historical event in transportation on the continent occurred at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869, as the Union Pacific tracks joined those of the Central Pacific Railroad. Leland Stanford, Collis P. Huntington, Charles Crocker and Mark Hopkins were the “Big Four” that conceived this enterprise and brought it to a successful ending after years of daily struggle that would have exhausted the patience and spirit of ordinary men. Huntington looked after the financing of the company. Crocker, with his tremendous energy, forced the construction of rails over the snow-crested Sierra and across the burning deserts of Nevada and Utah. Stanford kept his energies on the main points leading to success, and Hopkins saw that none of the money was wasted. That pioneer railroad line of the middle ’60s formed the basis of the gigantic Southern Pacific system. The connection of the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific bridged the 2000 miles to the Missouri River, and the four to six months time taken by the overland pioneers was reduced to six days. At once the Pacific States were transformed, and Western life gradually caught up with the life and aspirations of the East. A transcontinental railroad had been dreamed of as early as 1836. From time to time it was suggested by visionaries and discussed by the orators and newspapers of the ’40s and ’50s. In 1853 Congress expended $150,000 in hunting a feasible route. Surveys were made from time to time. The California Legislature took a hand in the issue in 1855-6, fearing that Congress might relax its energies, and urged a speedy construction of a railroad, but the jealousy of politicians delayed the initiative. Meanwhile short line railroads were developing in the Middle West. Some of these united, and systems began to develop. Leland Stanford is generally given credit for the initiative in starting the enterprise. In passing the store of Collis P. Huntington in Sacramento, one day, he noticed one of the huge freight wagons being loaded for the arduous haul over the Sierra into Nevada. Traffic was developing rapidly, and he realized that a better carrier and faster service was demanded. He and Huntington talked the matter over. Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker were drawn into the discussion; they all agreed that the time had come for a railroad connection with the East. Theodore Judah, for whom Judah Street is named, had surveyed a route over the Sierra and had interested Stanford in its practicability. He was sent for, and backed with money to go over several surveyed routes known and select the best one. Meanwhile, the corporation organized with Leland Stanford as president, C.P. Huntington as vice-president, and Mark Hopkins as treasurer. Charles Crocker was a leading direction, and the spirit of dominant energy in pressing construction through and over all obstruction. This is Central Pacific locomotive No. 1, the first engine to be placed in construction service on the western end of the transcontinental railroad. The maiden trip was made at Sacramento, November 11, 1863, after having arrived from the East on a clipper ship via Cape Horn. This locomotive was named in honor of Leland Stanford, then California’s governor, and one of the “Big Four” builders of the Central Pacific. San Francisco News Letter September 1925 Return to top of page CONTENT LITERACY STRATEGY FORMAT NAME OF STRATEGY: Directed Reading Activity ADAPTED FROM: McKenna, M., & Robinson, R. (2009). Teaching through text: Reading and writing in the content areas. p.59-98 CONTENT AREA: Social Studies GRADE LEVEL: 5 TEXTBOOK AND PAGES ADAPTED: Bower, B. , Lobdell, J. (2001) History Alive! America’s Past, Palo Alto, CA: Teacher’s Curriculum Institute, p. 208 OBJECTIVE: I will show that I understand how asking questions can show me the importance of finding out about an event by reading a passage from a history text book answering some questions and asking other questions to understand the importance of what I read. GLE 5.2.1 understands how essential questions define the significance of researching an issue or event. MATERIALS NEEDED: Sheet with questions for directed reading, agenda written on large paper. ACADEMIC ENGLISH: goods, products, industries, dramatic, transcontinental, canals, steamboats, factories, offices, quantities, carriages, skyscrapers. Signal words: After, Before, By, The first, Now, More and more. Appositives: Example: During this time, new industries, or businesses, caused such dramatic changes that together they are called a “revolution.” Cause/Effect relationships After the Civil War, the Industrial Revolution changed the way Americans lived and worked. During this time, new industries, or businesses, caused such dramatic changes that together they are called a “revolution.” The first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. Now people and goods could travel across the entire United States in a week. PROCEDURES: 5. Go over agenda: 6. Develop readiness for activity: “We have just finished studying the Civil War, and in that time period, most Americans lived very similar to the way their grandparents lived, in the countryside. After the Civil War, lives changed dramatically, and that change is what we are going to read about today. Some vocabulary that may be new to some of you is listed here. Take one minute and read the list of words, underlining the words you don’t know. Raise your hand if you have a word you don’t know. 7. Set purposes for reading. While you’re reading this passage, think about and answer the following questions and be prepared to share examples: And come up with one question of your own that asks why about something in the reading that is not answered there. - - In what ways did ways of life change after the Civil War? (went from living on farms in the countryside to living in cities, went from working farms to working in city factories, rode horses to driving cars, riding in trains and steam boats, went from making their own necessities to buying premade productos…) Did the changes in ways of life last? Do we still use technologies that the old ways changed to? (Telephones, cars, trains, premade products…) What ways of life are different for us than for our grandparents? (cell phones, cd’s, gps,…) What would you invent to make our lives better? Why? ( individual) 3. Arrange for students to read silently. I’ve put the passage for reading in the center of the table, along with a question sheet that goes with the reading. Each of you takes one and begins reading, answering your question sheet as you go. Remember to also come up with a new question of your own. 8. Discuss what has been read. How did you use the questions to help you understand what you read? How did the questions help you understand the importance of finding out about what I read? 9. Extend student understanding of the material. PISL Tell how asking essential questions shows you the importance of finding out about the industrial revolution. Use examples from the reading to support your answer. Have you used this question asking strategy before to find out about a different event? Question Level of Bloom's In what ways did ways of life change after the Civil War? Remembering Purpose for asking/how it is related to objective Did they understand the content of the reading passage/ connect with material in order to begin Did the changes in ways of life last? Do we still use technologies that the old ways changed to? Examples? Applying What ways of life are different for us than for our grandparents? Examples? Analyze What would you invent to make our lives better? Why Creating to understand importance of event Can student use information and connect it to their life?/ Understanding importance of event in relation to own life. Can student use information and connect it to their life?/ Understanding importance of event in relation to own life. Identifying how questions help connect importance to events. Can student use information and connect it to their life? / Understanding importance of event in relation to own life. Identifying how questions help connect importance to events, and use that knowledge. ASSESSMENT RUBRIC In what ways did ways of life change after the Civil War? Beginning General terms(lived and worked) Approaching 1 specific example of lived and worked changes(from farms to cities, worked on farms to worked in factories) Meeting 2 specific examples of lived and worked changes(from farms to cities, worked on farms to worked in factories AND made their own things to buying premade products) Exceeding More than the two examples and/or extrapolating that candles were the previous method of lighting before electric lights. Did the changes in ways of life last? Do we still use technologies that the old ways changed to? Answer yes Yes, and one example of what change from the Industrial Revolution we still use(phones) What ways of life are different for us than for our grandparents? One example of Two examples how their life is different than their grandparents Yes, and two examples of what change from the Industrial Revolution we still use(phones, cars) Three examples Yes, and three or more examples of what change from the Industrial Revolution we still use(phones, cars, trains) Four examples search index by subject by year biographies books SF Activities shop museum contact Plan for the Pacific Railroad, by Theodore Judah Biography of Theodore Judah The Big Four Driving the Last Spike The greatest historical event in transportation on the continent occurred at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869, as the Union Pacific tracks joined those of the Central Pacific Railroad. Leland Stanford, Collis P. Huntington, Charles Crocker and Mark Hopkins were the “Big Four” that conceived this enterprise and brought it to a successful ending after years of daily struggle that would have exhausted the patience and spirit of ordinary men. Huntington looked after the financing of the company. Crocker, with his tremendous energy, forced the construction of rails over the snow-crested Sierra and across the burning deserts of Nevada and Utah. Stanford kept his energies on the main points leading to success, and Hopkins saw that none of the money was wasted. That pioneer railroad line of the middle ’60s formed the basis of the gigantic Southern Pacific system. The connection of the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific bridged the 2000 miles to the Missouri River, and the four to six months time taken by the overland pioneers was reduced to six days. At once the Pacific States were transformed, and Western life gradually caught up with the life and aspirations of the East. A transcontinental railroad had been dreamed of as early as 1836. From time to time it was suggested by visionaries and discussed by the orators and newspapers of the ’40s and ’50s. In 1853 Congress expended $150,000 in hunting a feasible route. Surveys were made from time to time. The California Legislature took a hand in the issue in 1855-6, fearing that Congress might relax its energies, and urged a speedy construction of a railroad, but the jealousy of politicians delayed the initiative. Meanwhile short line railroads were developing in the Middle West. Some of these united, and systems began to develop. Leland Stanford is generally given credit for the initiative in starting the enterprise. In passing the store of Collis P. Huntington in Sacramento, one day, he noticed one of the huge freight wagons being loaded for the arduous haul over the Sierra into Nevada. Traffic was developing rapidly, and he realized that a better carrier and faster service was demanded. He and Huntington talked the matter over. Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker were drawn into the discussion; they all agreed that the time had come for a railroad connection with the East. Theodore Judah, for whom Judah Street is named, had surveyed a route over the Sierra and had interested Stanford in its practicability. He was sent for, and backed with money to go over several surveyed routes known and select the best one. Meanwhile, the corporation organized with Leland Stanford as president, C.P. Huntington as vice-president, and Mark Hopkins as treasurer. Charles Crocker was a leading direction, and the spirit of dominant energy in pressing construction through and over all obstruction. This is Central Pacific locomotive No. 1, the first engine to be placed in construction service on the western end of the transcontinental railroad. The maiden trip was made at Sacramento, November 11, 1863, after having arrived from the East on a clipper ship via Cape Horn. This locomotive was named in honor of Leland Stanford, then California’s governor, and one of the “Big Four” builders of the Central Pacific. San Francisco News Letter September 1925 Return to top of page