predictors of participation in an animal-assisted

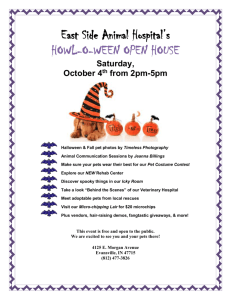

advertisement

PREDICTORS OF PARTICIPATION IN AN ANIMAL-ASSISTED ACTIVITY PROGRAM Stacie Lynn Davison B.A., San Diego State University, 2003 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in PSYCHOLOGY at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2010 PREDICTORS OF PARTICIPATION IN AN ANIMAL-ASSISTED ACTIVITY PROGRAM A Thesis by Stacie Lynn Davison Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Dr. Oriel Strickland __________________________________, Second Reader Dr. Caio Miguel __________________________________, Third Reader Dr. Larry Meyers ____________________________ Date ii Student: Stacie Lynn Davison I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator ___________________ Dr. Lisa M. Bohon Date Department of Psychology iii Abstract of PREDICTORS OF PARTICIPATION IN AN ANIMAL-ASSISTED ACTIVITY PROGRAM by Stacie Lynn Davison The purpose of this study was to assess the significance of demographic variables, depression, and pet attitude as predictors of willingness to participate in animal-assisted activity (AAA) programs. The final sample included 57 residents at assisted-living centers in California, most of whom were Caucasian (91%), with a mean age of 82, and a college education (44%). The Pet Attitude Scale (PAS), Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), and a newly developed scale to measure interest in an AAA program were used in this study. PAS scores and gender were found to predict willingness to participate in an AAA program. These results contribute to the literature surrounding AAA, which has not yet documented predictors of participation among senior citizens. Gaining information about factors that influence participation could be helpful to care providers to address the needs and interests of residents at assisted-living centers. _______________________, Committee Chair Dr. Oriel Strickland _______________________ Date iv DEDICATION In memory of my parakeet, Bubbles: The comfort, joy, and love you brought into my life was the inspiration for this thesis. I love you little bird. To my family: Mom, Dad, Vicki, Neno, Matt, and Lucas, thank you for your unconditional love and support. I could not have done it without you. I love you. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to the staff and residents at Carlton Plaza, Sunrise Assisted Living, Aegis and The Palms for allowing me to conduct my study, especially to those that took me in, unannounced. Thank you to Marilyn Royce at Carlton Plaza for taking time out of your busy schedule to help in planning times to collect data, for introducing me to the residents, and for being the first to approve my data collection. Thank you to my graduate committee Dr. Strickland, Dr. Miguel, and Dr. Meyers. Thanks to Mom and Neil Moore for buying me computers. A special thanks to all of my cheerleaders: Mom, Dad, Vicki, Neno, Matt, Lucas, Kendra, Brad, Nick, Cheryl, Becky, Deborah, Mary K, Remy, Neil, Debbie, Jason, Chris, Heather, Chicca, Nancy, Lesley, Barbara, Terry, Judy, Uncle Joe, Aunt Marie, Uncle Albert, Aunt Jenny, and anyone else that contributed in any way. Your unbelievable generosity, encouragement, and your love and support mean the world to me. I am so lucky to have you in my life. Thank you! vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Dedication ...................................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgments........................................................................................................................ vi List of Tables ............................................................................................................................. viii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................1 Animal-Assisted Activity and Well-being .........................................................................3 Attitude Toward Pets .........................................................................................................7 Gender ..............................................................................................................................9 Depression .......................................................................................................................10 2. METHOD ...............................................................................................................................12 Participants ........................................................................................................................12 Materials............................................................................................................................12 Procedure ..........................................................................................................................13 Agency Settings ................................................................................................................14 3. RESULTS ...............................................................................................................................16 Data Screening .................................................................................................................16 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Study Variables.....................................17 Tests of Hypotheses .........................................................................................................18 4. DISCUSSION .........................................................................................................................21 Strengths and Limitations ................................................................................................22 Directions for Future Research ........................................................................................23 Appendix A. Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale .........................................27 vii Appendix B. Pet Attitude Scale .................................................................................................28 Appendix C. Participation Scale ................................................................................................29 References .....................................................................................................................................30 viii LIST OF TABLES Page 1. Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for Study Variables ……….. 18 2. Table 2 Regression Analysis for Predictors of Participation ………….……………...20 ix 1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION In the United States, advancements in the medical field such as improved medications, exercise, health education, and nutrition have helped to extend the expected human life span (Serpell, Kruger, Katcher, et al., 2006). According to a report by the US Census Bureau (2009), the global population of people aged 65 or older is expected to triple by the year 2050, and for the first time the elderly population will outnumber children under 5 years old. In the United States alone there are close to 40 million senior citizens (people 65 years and older) that comprise 12.8% of the population. As we watch the elderly population grow, our attention should focus not only on living longer, but also on living well. Although what it means to live well varies from person to person, living well into old age may include factors such as independence, having a social support network, physical mobility, low incidents of stress, depression, and being relatively free of chronic ailments. Many elderly Americans live in long-term care facilities. According to a 2002 estimate, there were more than 600,000 elderly Americans living in assisted-living facilities, and that number projected to increase by 15 to 20 percent each year (Cummings, 2002). In 1987, Ronald Reagan signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) in response to concerns over the quality of nursing home conditions and services. The main goal of OBRA was for residents to “attain and maintain her highest practicable physical, mental, and psychosocial well-being” (U.S. Congress, 1987). One of the provisions of the act mandated all nursing homes to provide activities that meet the residents’ interests and that help to reach the goal of providing a higher quality of life. The findings of several empirical studies provide clear justification for OBRA’s mandate to provide activities of interest to nursing home residents (Voelkl, Fries, & Galecki, 1995). Results from various studies have shown that activities can improve physical function by 2 increasing flexibility and ambulation, as well as psychological factors such as improved affect, mental status, morale, and self-esteem (Wolfe, 1983; McGuire, 1984; Iso-Ahola, 1989). A common and important goal of activities at long-term care facilities is to provide residents with social interactions, which can decrease loneliness, maintain or stimulate mental functioning, and increase awareness and connection with the external environment (Bernstein, Friedmann, & Malaspina, 2000). According to Lawton (1983), activity preferences in older adults develop from previous experience, familiarity with the activity, assessment of the present situation, and estimated outcomes of participation in the activity. Mannell (1980) defines satisfaction in participating in an activity as a transient psychological state characterized by decreased awareness of surroundings and the passage of time, and accompanied by positive affect. The satisfaction derived from participating in activity is directly linked to the affect or from the personal meaning associated with performing an activity (Lawton, 1983). Lawton’s Activity Model shows that meaning, expectations, and familiarity determine activity preference and the positive affect derived from satisfaction leads to well-being (Lawton, 1983). Many long-term care facilities utilize animal-assisted activities (AAA) as a way to improve the quality of life for their residents. The Delta Society defines AAA as recreational interactions between people and animals that may provide, “motivational, educational, recreational, and/or therapeutic benefits to enhance the quality of life” (Standards of Practice, 1996). Elderly care centers frequently offer both animal-assisted activity and animal-assisted therapy programs. AAA differs from animal-assisted therapy in that animal-assisted therapy is goal directed, provided by specially trained professionals, and progress is measured (Standards of Practice, 1996). In animal-assisted therapy, the animal is used to facilitate learning and to improve conditions. For example, someone with mobility difficulties might take a therapy dog for 3 a walk to help improve ambulation or one could learn sequencing by learning the steps in brushing a dog. AAA allows for spontaneous visits, a wide array of settings, and a focus on the recreation and emotion associated with the animals. People with a variety of skill levels, from professionals to volunteers, may deliver AAA because it is not goal-directed and they are not required to take notes on an individual’s progress in the program (Serpell et al., 2006). Although AAA covers a wide range of human-animal interactions, in this study AAA specifically entails volunteers bringing a trained dog for either one-on-one or group visits. The participants control each visit’s length and activities. For instance, some may choose to view the animal from a distance, while others may prefer to pet or brush the animal. The Selective Theory of Aging states that as individuals move into old age, they take stock of their life and decide which activities they find satisfying and can successfully maintain. The activities that they are no longer able to maintain are abandoned (Maynard, 1974, 1986).While it is common for residents to be fond of pets, many are unable or unwilling to care for a pet on their own. Through AAA, elderly people can experience the enjoyment and benefits of interacting with an animal without the responsibility of owning a pet. AAA was selected for the current study instead of AAT, because it covers a wide range of human-animal interactions, it can be provided by most anyone, it is frequently available in assisted-living centers, and people of all physical and mental capabilities may participate. Animal-Assisted Activity and Well-Being Kahana, Liang, and Felton (1980), found that nursing home residents prefer environments that are socially active and stimulating. The quality and quantity of an individual’s social network affects the ability to handle stress, as well as, level of life satisfaction. Studies have shown that the mere presence of an animal can facilitate person-to-person interactions (Wells, 2007). One 4 study mentioned an increase in social interactions among residents in the AAA treatment group where they noted that the residents talked to each other about the dog (LeRoux & Kemp, 2009). In a study by Bernstein, Friedmann, and Malaspina (2000), the researchers used naturalistic observation to compare aspects of social interaction during both animal and nonanimal activities at long-term care facilities. The categories for observation were type of activity (animal activity and non-animal activity), type of social interaction (brief conversation, long conversation, and touch), and cognitive status of the resident (alert, semi-alert, non-alert). The researchers observed similar patterns of social behavior for all cognitive status levels. Although the residents in the non-animal activity group engaged in more brief conversations, the residents in the AAA alert group engaged in more long conversations during the animal activity. The animals seemed to serve as facilitators for human socialization by giving the residents something novel with which to talk and interact. Having an animal present not only added to the quality of the social interaction, but also increased the resident initiation of social interactions even with the least alert residents. Additionally, the results of the study showed that while neither the animal nor the nonanimal activities were effective at increasing touching behaviors among residents, the animal activity provided significant amounts of touch if petting the animals was included. Touching the animals provided participants of all alertness levels significant amounts of tactile stimulation and physical contact. Touching cats has been rated as important as touching another human and has been shown to have beneficial health effects (Zasloff & Kidd, 1994). Allostatic load is the cumulative effects of the body’s repeated adaptations to stressors and has been associated with overall physical and cognitive decline in the elderly (Seeman, Singer, Rowe, Horwitz, & McEwen, 1997). Long-term and repeated stress has been linked to high blood pressure, diabetes, and heart disease (Baun. Johnson, & McCabe, 2006). Reducing 5 one’s allostatic load is essential in preventing and minimizing illness, as well as, maintaining physical and cognitive function (Baun et al., 2006). Research has demonstrated that physiological arousal indicators lower in response to human-animal interactions (Baun et al., 2006). According to Serpell (2006), human-animal interactions provide stimulation for all five senses; this stimulation leads to greater well-being by changing neurochemicals in the brain. Some of these chemicals, such as dopamine and epinephrine, can produce positive moods and relaxation, which allows for a decrease in blood pressure. Interacting or merely being in the same room as a dog can reduce the human heart rate and blood pressure by lowering the human body’s autonomic responses to stressful situations (Wells, 2007). The results of a study by Barker, Knisely, McCain, Shcubert, & Pandurangi, (2010), showed a trend of relaxation associated with interacting with an unfamiliar dog (AAA group). Whereas dog owners tended to report less perceived stress, the AAA group showed greater reductions in physiological measures. Heart rate, diastolic blood pressure, and cortisol levels all lowered below baseline for sixty minutes after the dog interaction for the AAA group. The conclusions that can be drawn from this particular study are limited due to the small sample size (dog owners; n = 5, and AAA group; n = 5) and due to lack of a control group. However, the effects appear to be substantial because the measurements of all variables (except for amylase and systolic blood pressure) dropped and stayed below baseline after the interaction, suggesting a buffering effect. In an experiment by Francis (1991), puppies were brought into an adult home for elderly patients with chronic psychiatric conditions to see if the animal visitors would increase health self-concept, life satisfaction, psychological well-being, social competence, social interest, personal neatness, psychosocial function, and mental function, and reduce depression. In this 6 study, seven of the nine factors studied showed statistically significant improvement. The only two areas that did not improve were personal neatness and health self-concept. At the beginning of the study, when the researcher asked the residents if they wanted to participate, only a small number enrolled. On a hunch, the researchers brought crates containing puppies and let them loose in the nursing home; consequently, the number of participants instantly tripled. Even residents with mobility difficulties and those who were formerly withdrawn came out of their rooms to greet the puppies. The residents were overjoyed by the puppies and eagerly awaited future visits. The focus of Francis’ study, and something that many other AAA studies mention, is the participants’ emotional response to animals. The joy, comfort, and excitement of interacting with an animal are responses that can easily be observed, but not easily measured. Animals’ greeting rituals, naturally affectionate disposition, loyalty, and widely perceived ability to love unconditionally may all serve to promote feelings of self-worth and self-esteem (Wells, 2007). Helping to shift resident’s focus from ailments and day-to-day struggles to that of pleasure is an important goal. As one AAA researcher noted, “smiles could not be counted separately, as the participants smiled throughout the entire visit” (Colby & Sherman, 2002). It is the sheer joy and smiles that residents, staff, and volunteers experience that during AAA visits that are perhaps the most important benefits. After all, the main objective these activities are to promote well-being and quality of life. The literature review thus far has introduced AAA and its relationship to various physical and mental health outcomes. A recently published article (Collins et al., 2006) reviewing the relationship between psychosocial well-being and community participation of service dog partners called for the need for future research to investigate factors influencing participation. Addressing this call, and the potential practical, physical, and psychological benefits of AAA, this 7 study was designed to assess the significance of various predictors of interest in participation in animal-assisted activity programs at long-term care facilities for the elderly. Gaining information on factors that influence willingness to participate will be helpful to care providers to address the needs and interests of the residents. If residents indicate that they are interested in AAA, then perhaps this study could serve as a catalyst for connecting animal visitation groups with interested parties. There has been a growing interest in the benefits of activities involving human-animal interactions; however, no studies have investigated voluntary participation in an animal-assisted activity program. Researchers have been interested in the possible benefits that these humananimal interactions provide, as well as what mechanisms may be driving these interactions. This study will add to the current literature by exploring the driving forces behind individual’s willingness to interact with animals through an animal-assisted activity program. This is important for the field of AAA because practitioners need to be able to identify characteristics of potential participants and/or aspects of their background that would lead them to want to participate. The current study will contribute to the literature by examining demographic variables such as ethnicity, gender, pet ownership, education, and age, in addition to the main variables of CES-D scores, PAS scores and their relationship to scores on the AAA participation scale. In the following section, each of the variables will be considered in drawing predictions about their relationship to participation. Attitude Toward Pets Templer et al. (1981) developed the Pet Attitude Scale (PAS), which is an 18-item Likerttype scale that measures three factors regarding pets: love and interaction, pets in the home, and joy of pet ownership. Some research has explored the relationship between the PAS and various 8 outcomes, although none have explored its relationship to participation in an AAA program. Jenkins (1986) used the PAS to determine positive regard toward dogs that participants petted to lower their blood pressure. Hama, Yogo, and Matsuyama (1996) found that people who scored higher on the PAS had greater reduction in the mean arterial pressure and systolic pressure when petting dogs. The PAS was found to correlate positively with childhood animal bonding (Brown, 2000). Finally, kennel workers were found to have significantly higher scores on the PAS than social work students (Templer, et al., 1981). One of the key theoretical approaches to understanding the impact of pets on people is Bowlby’s Attachment Theory, which is based on the emotional bond formed between a human infant and its caregiver. The primary infant behavior associated with attachment theory is the seeking of proximity to an attachment figure, usually the primary care giver, in stressful situations. This attachment serves the biological function of protection and security and the capacity to form bonds can be generalized to others. Ainsworth (1989) proposes that dogs and cats can also provide an emotional bond of attachment that promotes a sense of well-being and security. The idea that mere exposure can facilitate attachment can explain why people who are exposed to pets earlier in life are more interested in them as they get older (Sable, 1995). Animals have also been recognized as having motivating effects on humans. For example, they often motivate humans to go on a walk (Serpell, 1991) and they have been recorded as motivating individuals with mobility difficulties to walk (Francis, 1991). Animals may act as a catalyst in human participation for individuals with positive attitudes toward pets by making the activity enjoyable and worthwhile, more so than if that activity did not involve an animal. Although there have been no other studies that have directly examined pet attitude and participation, attachment theory would suggest that people who hold more positive attitudes 9 towards pets would be more interested in participating in an animal-assisted activity program. Hypothesis 1.It is hypothesized that there will be a positive relationship between scores on the Pet Attitude Scale (PAS) and interest in participation in an AAA program. Gender Some research has assessed gender differences in pet ownership and attitude toward pets. Risley, Holley, and Wolf (2006) investigated the human-animal bond and ethnic diversity. They found that the majority of their female participants (60%) owned companion animals. In a study by Prato-Previde, Fallini, and Valescchi (2006) there was shown to be a difference in the way that males and females interacted with their pets, such that females tended to respond to the presence of a pet more readily than males. In addition, Marks, Koepke, and Bradley (1994) found that females had slightly more positive scores on the Pet Attitude Scale than males. Al-Fayez, Awadalla, Templer, and Arikawa (2003), found Kuwaiti PAS scores for both male and females correlated more highly with the score of their fathers than with the scores of their mothers. This finding was different from those found with Americans where the PAS score of adolescents correlated more highly with their mothers. This contrast appears to be consistent with the father’s dominant role in Arab families. In one study, researchers tested oxytocin levels before and after owners interacted with their pet dog(s) after arriving home from work (Miller et al., 2009). Oxytocin (OT) is a hormone that promotes feelings of relaxation and facilitates bonding, attachment and socialization. In the study, there were 10 men and 10 women and each gender group was assigned to either a reading condition or a dog interaction condition. The results showed that women’s oxytocin levels rose significantly after interacting with their dog. The oxytocin levels decreased in all other groups and conditions. Oxytocin is believed to be responsible for eliciting the calm, relaxed feeling that the female participants felt after they had interacted with their pet dog as well as maternal and 10 pro-social behaviors. Due to findings that females are more likely to own a pet, have a chemical response to their pets that elicits feelings of bonding and attachment, and have slightly higher scores on the PAS, the researcher formulated the following hypothesis. Hypothesis 2. It is hypothesized that there will be a main effect of gender on participation, with females being more interested in participating in an AAA program than males. Depression The companionship and nurturing instinct that animals bring out in humans may have a positive effect on depression and loneliness (Miller et. al., 2009). Depression is one of the most common emotional and psychological disorders, affecting approximately 20% of elderly people living in long-term care facilities (Zullo, n.d.). Depression can intensify the effects of co-existing physical illnesses such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, and diabetes (National Instititue of Mental Health, n.d.). Sounter and Miller (2007) conducted a meta-analysis to see if AAA could effectively treat depression. In order for a study to be included in the meta-analysis it had to include random assignment, a comparison or control group, use of AAA or AAT, a self-report measure of depression, and report sufficient information to calculate effect sizes. Five studies met all of the requirements for the meta-analysis (four dissertations and one conference paper). Four of the five studies used in the analysis showed a significant reduction in depression from pre-test to post-test for participants in the AAA group. The review supported the hypothesis that AAA effectively alleviates depression. The release of endorphins in the brain elicited by human-animal interactions is one explanation for the reduction in depression following the participation in AAA (Allen, 2001). Thus, research has demonstrated that depression is lower among residents after participation in AAA; however, an important question is whether depressed participants would be 11 less likely to choose to participate in a voluntary program. Depression is common among nursing home residents, as they often face difficult life transitions such as losing a loved one, experiencing diminished physical and mental abilities, and displacement from their home. Cummings (2002), interviewed residents at assisted-living centers on variables including depression, life satisfaction, functional status, perceived health, perceived social support, and participation in activities. She found that the variables that were linked to higher rates of depression were increased functional impairment, poor health, female gender, and perceived lack of social support. However, when residents reported high levels of social support, gender, functional impairment, and other health measures were no longer significantly linked to depression. Therefore, providing activities for residents, and encouraging relationship building among residents and between staff members were suggested ways to improve social support and decrease depression. Voekel et al. (1995) studied factors predicting nursing home residents’ participation in activities provided by their living facility. They hypothesized that personal competence variables including activities of daily living, health, cognition, and competence would influence elderly activity involvement. Depression was a personal competence variable that was shown to be associated with reduced participation. It seems that people who are depressed frequently lack the energy to participate and have difficulty experiencing pleasure, which drives participation. Residents who were not depressed spent more time in activities than residents that were depressed. Due to research findings and logic that depression is generally linked to lower levels of participation: Hypothesis 3.It is hypothesized that there will be a negative relationship between depression scores on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) and interest in participation in an AAA program. 12 Chapter 2 METHOD Participants The participants in this study were residents at senior living centers in Sacramento and Ventura, CA. Fifty-seven participants (41 female, 16 male) completed a packet of surveys. The participants ranged in age from 64 to 96 years of age and had a mean age of 82. There were 52 Caucasian (91%), 3 Latino/Latina (5%), 1 African American (2%), and 1 Native American (2%) participants. The majority of participants had a college education, with 44% having an Associate’s degree or higher. Twenty-four participants owned a pet (42%) and 33 did not (58%). The majority of participants (90%) reported that they were not allergic to animals. Materials Demographic information. Demographic data was collected using a demographic sheet that contained questions on gender, age, education, ethnicity, pet ownership, and animal allergies. The living facility of the participant was also documented. Depression scale. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977) is used to measure how frequently depressive symptoms are experienced in a week time span. The CES-D contains 20 questions rating negative and positive affect such as “I felt depressed,” and “I was happy.” The items are measured on a 4 point scale ranging from 0 = not at all to 3 = almost all the time. Positive items are reverse coded. A score of 16 or higher typically indicates that an individual is at high risk for depression. Please refer to Appendix A for a copy of the full scale. The CES-D has well-established normative reliability and validity data with inter-item reliability ranging from .80 to .90 and test-retest reliability ranging from .40 to .70, as well as 13 correlations with the Beck Depression Inventory >.80. The CES-D has strong psychometric sensitivity for identifying symptomatic individuals, has been tested on people of a wide range of ethnicities, and has been translated into several different languages. For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha score of internal consistency reliability was .78. Pet attitude scale. The Pet Attitude Scale (PAS) (Templer et al., 1981) measures three factors regarding pets: love and interaction, pets in the home, and joy of pet ownership. The PAS is an 18-item, paper and pencil, Likert-type scale. The items are measured on a 7-point scale ranging from 1= strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Some examples from the PAS are, “I love pets”, “I hate pets”, and “Pets are fun, but it’s not worth the effort of owning one.” The PAS has a reported Cronbach’s alpha of .91 and a reliability of .92 (Al-Fayez et al., 2003). The value of Cronbach’s alpha for the current study was .87. Please refer to Appendix B for a copy of the PAS scale. Participation in AAA. There are no existing measures in the literature for interest in participating in an animal-assisted activity program. A measure was developed by the author of the thesis in which the participants were asked to rate on a scale from one to seven (strongly disagree to strongly agree) interest in various aspects of participating in an animal-assisted activity program if one were made available at their care facility. These items demonstrated strong internal consistency reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of .88. The items on this measure can be found in Appendix C. Procedure The researcher first obtained ethical approval from the psychology department’s Human Subjects Committee. Next, the survey packets were distributed with the consent form on the front of the packet and the participants were asked to read and sign the consent form. After the participant signed and returned the survey packet, the researcher removed the consent forms from 14 the survey packet to ensure confidentiality. Following that, the researcher returned the packet of materials to the participants. The survey packet contained a demographic sheet, and three surveys: the CES-D Depression Scale, the Pet Attitude Scale, and the AAA Participation Scale. If the consenting participant was unable to read or write on his or her own, the researcher asked the questions on the survey and wrote down the participant’s responses. After participants completed filling out the inventories, the researcher collected the packets and placed them in an envelope separate from the consent forms to ensure participant confidentiality. The researcher then orally debriefed the participants, answered any questions, and handed out the debriefing page for participants to keep. The researcher thanked each participant for his or her participation. Agency Settings The researcher collected data at six assisted-living centers in Sacramento, CA and Ventura, CA: Carlton Plaza Senior Living Center (n = 15), Sunrise Assisted Living, Munroe Center (n = 4), Sunrise Assisted Living, Carmichael Center (n = 3), Aegis Living (n = 4), and The Palms at Bonaventure (n= 35). Carlton Plaza Senior Living is family owned and has been supporting seniors for more than 20 years. Their mission is to empower residents through their continuum of care services. As the residents’ health needs change, so does the level of support. Carlton Plaza offers a wide array of services to support residents’ every day needs and to nurture all aspects of the residents’ lifestyles. Carlton Plaza is located in Northern California and offers six living facilities throughout the Bay Area and Sacramento (www.carltonseniorliving.com). Sunrise Assisted Living was founded in 1981 with a mission to champion quality of life for all seniors. Sunrise provides personalized independent and assisted living, care for individuals with memory loss, as well as nursing and rehabilitative services. Sunrise Senior Living currently offers 415 locations in the U.S, Canada, Germany, and the U.K. (www.sunriseseniorliving.com). 15 The Palms at Bonaventure in Ventura, CA offers health and personal care provided by licensed nurses. Some of the amenities that are offered include beautifully designed common areas, chef-prepared meals, a library, a whirlpool, and a movie room with complimentary refreshments. The Palms makes activity involvement an integral part of life by providing a variety of activities to choose from daily. A memory care unit is available with a caring staff, and a safe living environment that combines the comfort of home with a physical design that was created to enhance the quality of life for residents with memory impairments (www.seniorlivinginstyle.com). Aegis of Carmichael is located in a residential neighborhood and is characterized by its ‘small town’ feel. The staff members at Aegis are committed to providing a friendly environment and specialize in caring for residents with Alzheimer’s disease. On top of friendly, individualized care the residents are offered weekly happy hour and entertainment as well as frequent trips to places like the Crocker Art Museum and River Cats baseball games (www.seniorsforliving.com). All of the facilities currently keep at least one resident pet dog the common area with which the residents are free to interact. Some of the larger homes allow residents to keep their own pets in their rooms. 16 Chapter 3 RESULTS Data Screening All variables were first screened for the presence of outliers, defined as being three standard deviations outside the mean. In addition, the shape of the distribution was examined to check that all variables were approximately normally distributed by examining the Q-Q plots and Shapiro-Wilk’s test for normality. Most variables were approximately normally distributed, with two exceptions in terms of outliers. The CES-D had an interesting distribution, with a low score of 0 (no depressive symptoms) and a high score of 44 (out of a possible 60, indicating maximum depression symptoms). The average variation around the mean of 12.2 was 10.39, meaning that scores above 43 fell outside the 3-standard deviation cut-off. There was one score of 44, and two additional scores next to this measure. It was decided not to include these scores in the analysis due to their extreme values (suggesting high levels of depression) because these three participants might drive results that would be un-representative of the other participants. In the interest of confidentiality, these participants were not individually identified, but a plan was made to communicate to their agency settings that we had identified significant depression among some of the residents at their location. There was one outlier for age. As mentioned above, the average age was 81.7 (SD = 7.44), with the youngest participant being aged 57 and the oldest being 96 years old. Although we had no reason to suspect that this lower outlier would affect the results, in the interest of consistency in decision-making, we did not include this participant in subsequent analysis. The removal of outliers from the data set resulted in losing four respondents’ data, for a total new sample size of 57 participants. It should be noted that the analyses were re-run including all participants and none of the findings from the second analyses were different. For 17 clarity of presentation, results will be presented using the attenuated data set. To ensure that the dependent variable did not vary as a function of the facility from which participants were studied, an analysis was conducted to compare these facilities. The results of a one-way ANOVA indicated that the participation scores did not significantly differ between participants based on living facility, F (4, 56) = .26, p > .05. Thus, this variable does not need to be used as a control in subsequent analyses. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Study Variables Means and standard deviations for all continuous variables are presented in Table 1. The average level of education represented in the sample was “some college” (M = 6.67, SD = 1.75). The mean score for PAS was 5.40 (SD = 1.06) indicating an overall moderately positive attitude toward pets. The average score on the CES-D was 10.07 (SD = 7.20). The average participation score revealed an overall neutral attitude toward participating in an AAA program if one were available, with the mean score being almost exactly the midpoint of the scale (M = 3.89, SD = 1.86). Pearson product moment correlations are also presented in Table 1. Only two of the continuous variables were significantly related. Scores on the Pet Attitude Scale were negatively related to age r(57) = -.27, p < .05. Scores on the Pet Attitude Scale were significantly positively related to interest in participation in an AAA program r(57) = .47, p < .01. This correlation addresses one of the hypotheses and will be re-visited below. 18 Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for Study Variables Variable M SD 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 81.7 6.62 12.2 5.39 3.99 7.44 1.72 10.4 1.06 1.84 Age Education Depression Pet Attitude Participation 1 --.07 .06 -.27* -.05 _____ 2 3 4 5 --.02 -.04 -.07 (.78) .03 .17 (.87) .47** (.88) Note. Coefficient alphas are presented in parenthetical boldface along the diagonal. N= 57 for all analyses. *p < .05. **p < .01 Tests of Hypotheses The following section presents the tests of each of the demographic comparisons as well as the relationship between the PAS, CES-D, and AAA participation. The original analytic plan was to build a regression model that would maximize prediction of participation scores by entering significant demographic variables first, and then observing the contributions of the psychological variables of depression and pet attitudes. Because these variables have never been studied empirically, it was decided to build the model by first assessing the bivariate relationships among study variables. The final analysis will include a regression equation including all the significant variables to show the overall R squared. Gender and Participation. To assess the relationship between gender and participation, a one-way ANOVA was conducted. Results showed that the differences between the two groups were statistically significant F (1, 56) = 4.47, p < .05). A comparison of mean scores shows that men reported more interest in AAA programs (M = 4.66, SD = 1.67) than did women (M = 3.56, SD = 1.86). It should be noted that the direction of the gender effect is opposite from that 19 predicted by the literature, and this will be addressed in the discussion section. The results of the Levene’s Test were not significant (p = .15) therefore equal variances between male and female participation are assumed. Depression and Participation. The relationship between CES-D scores and participation were assessed via a Pearson Product Moment Correlation: This analysis showed no significant relationship, (r = .17, p > .05). Pet Attitude Scores and Participation. As mentioned above, the results of a Pearson Product Moment Correlation revealed a significant correlation between PAS scores and participation (r = .47, p < .01). Thus, this analysis revealed that PAS scores accounted for 21.6% of the variation in participation scores, leaving 78% of the variation in participation scores unexplained by pet attitude. Overall Regression in Predicting Participation Scores. The results thus far suggest that only gender and Pet Attitude Scores emerged as significant predictors of willingness to participate in an AAA program. A regression model was then run using both of these variables to assess the overall prediction of participation. Variables were included in the equation using the Stepwise method, entering gender first and then observing the independent prediction of the PAS. Results can be observed in Table 2. Considering both variables in the equation, 27% of the variance of participation scores can be predicted with gender and Pet Attitude Scales. 20 Table 2 Regression Analysis for Predictors of Participation ______________________________________________________________________________ Step and Predictor variable B SEB β R2 Δ R2 ______________________________________________________________________________ 1. Gender -.97 .47 -.24 .08 .08* 2. Pet Attitude Scores .78 .20 .45 .27 .19* ______________________________________________________________________________ *p < .05 21 Chapter 4 DISCUSSION In the current study, self-report measures of demographic variables, depression, and attitude toward pets were examined as possible predictors of willingness to participate in an AAA program. PAS scores and gender were found to be significant predictors of willingness to participate in an AAA program. These findings will be discussed as they relate to the relevant literature base. The hypothesis that individuals with higher scores on the Pet Attitude Scale (PAS) will be more likely to participate in an AAA program than those with lower scores on the PAS, was supported. This finding is consistent with the results of earlier studies explaining that people who are exposed to pets earlier in life are more interested in them as they get older (Sable, 1995) and that preferences and previous experiences determine participation. In the second hypothesis, it was predicted that females would be more interested in participating in an AAA program than males. This hypothesis was not supported; in fact, men were more interested in participation than women were. The findings of the current study are contrary to that of Voelkl (1995), where male residents were found to spend less time in activity programs than female residents. An F-test was run to determine whether the gender outcome was actually due to age. The F-test was not significant F(1,59) = .72, p > .05), therefore the gender outcome was not actually due to differences in age between males and females. In Herzog’s (2007) review of gender differences in human-animal interaction, it was noted that gender differences result from the interaction of many factors on many different levels, and can change over time. The third hypothesis that those who scored higher on the Center for Epidemiological 22 Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (more depressed) will be less likely to participate in an AAA program than those with lower scores (less depressed),was not supported. In a study by Matschinger et al., (2006), 986 individuals over 75 years of age were given the CES-D scale. Results of the study showed that care should be taken when administering the CES-D to an elderly population. Questions on the CES-D are worded both positively and negatively in an effort to avoid the respondent’s tendency to answer positively to each question regardless of its content. The results of the study showed that oppositely worded items do not necessarily solve the problem of respondent’s answering favorably to all items, and that they instead may distort the dimensional structure and reliability of the scale. On the contrary, an analysis of the CES-D, conducted by Lewinsohn et al., 1997, revealed that neither age, gender, cognitive impairment, functional impairment, physical disease, nor social desirability had a significant negative effect on the psychometric properties or screening efficacy of the instrument. Strengths and Limitations There were several limitations of this study, including the sample size, the self-report nature of the scales, the ordering of the scales, the convenience sample of the participants, the self-report of the data, and the length of survey given the age range of the participants. The small sample size limits both the statistical power as well as the generalizeability of the study. A convenience sample was used, not random sampling, and as a result the participants tended to be more active mentally, physically, and socially. All of the scales in the survey packet were arranged in the same order. This methodological error may have introduced practice effects, ordering effects, and/or hypothesis guessing. If this study were to be replicated, the ordering of the scales should be randomized. In addition, there was a considerable amount of resistance to the surveys from both the directors and residents, which is the reason for the small sample size. The directors were 23 concerned about maintaining resident privacy even after reassurance from the researcher that participant confidentiality was a top priority. The residents commonly felt either that the survey packet was too difficult to complete or were generally uncomfortable with the personal nature of the depression questions. One of the strengths of this study is that the specific topic of participation in an AAA program has not been studied before and it has important implications for the growing elderly population. Understanding the factors that drive participation is important because it is a way to help ensure that residents’ interests are being met. When residents participate in desirable activities, it is a way to promote life satisfaction and well-being. A second strength of this study was the development of a participation scale specific to AAA with high internal consistency reliability. This scale can be used by long-term care facilities and by other researchers to assess the level of interest in an AAA program. OBRA mandates all long-term care facilities to provide activities of interest to residents and the AAA participation scale may be useful to care providers in assessments of resident activity interests. Due to the findings that gender and PAS scores significantly predicted participation in an AAA program, this information could also potentially be used as to screen new residents or to periodically screen all current residents to determine if an AAA program would be a good fit at that location. Directions for Future Research Souter and Miller (2007) discussed the need for additional exploration of the relationship between AAA and depression. Future research should be conducted to identify the specific subfactors of depression that can be alleviated by a visit by an animal within an AAA context. Researchers might investigate whether it is factors such as the tactile stimulation, the social facilitation, or the non-judgmental nature of the visiting animals, which leads to decreased 24 feelings of depression following participation in an AAA program. With this information, the factors found to alleviate depression could be emphasized during AAA visits. Few studies have examined factors that influence people’s attitudes toward pets. The results of this study indicated that pet ownership positively influenced pet attitude. Future studies should explore the relationship between other factors such as gender, ethnicity, and loneliness on attitudes toward pets. Herzog (2007) reviewed gender differences in human-animal interactions and called for future studies that investigate the sources of gender differences in human-animal interactions and specifically mentioned that reports should include the effect sizes for these differences. Barker, et al. (2010) investigated the stress buffering response patterns from interacting with a therapy dog. He suggested that larger-scale studies are needed to replicate and test the differences in levels of stress reduction between dog owners and those interacting with an unfamiliar dog. Additionally, according to Barker et al. (2010), the strong inverse relationship found between pet attitude and perceived stress suggests that dog owners with positive attitudes toward pets may experience stress reduction from interacting with an unfamiliar dog, such as occurs in AAA. These findings emphasize the need to control for pet attitudes in human-animal interaction research. Le Roux and Kemp (2009) suggested that factors such as social interaction and loneliness should be explored in relation to an AAA program. Several studies have found pet ownership to be effective in reducing feelings of loneliness. To address loneliness as it relates to AAA programs, future studies should explore the factors that influence the ability of dogs to facilitate social interactions, such as type of animal, gender, and attitude toward pets, particularly in an AAA setting (Wells, 2004). Finally, future research should be conducted at assisted- living facilities where active AAA programs are already in place and assess the demographic factors, depression, loneliness, 25 and PAS scores in relation to actual, documented participation in the AAA program, instead of stated desire to participate. Additionally data on attitudes toward unfamiliar dogs or animals should be collected instead of pet attitude since unfamiliar animals are used in AAA programs. If this study were to be replicated in the future, I would recommend using shortened versions of the PAS and CES-D because of the fatigue factor and resistance to filling out the survey packet related to the length of the original scales. 26 APPENDICES 27 APPENDIX A Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Instructions: Circle the number for each statement that best describes how often you felt or behaved this way DURING THE PAST WEEK. 0 1 2 3 Rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day) Some or a little of the time (1-2 days) Occasionally or a moderate amount of the time (3-4 days) Most or all of the time (5-7 days) 1. I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me. 2. I did not feel like eating; my appetite was poor. 3. I felt that I could not shake off the blues. 4. I felt I was just as good as other people. 5. I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing. 6. I felt depressed. 7. I felt that everything I did was an effort. 8. I felt hopeful about the future. 9. I thought my life had been a failure. 10. I felt fearful. 11. My sleep was restless. 12. I was happy. 13. I talked less than usual. 14. I felt lonely. 15. People were unfriendly. 16. I enjoyed life. 17. I had crying spells. 18. I felt sad 19. I felt like people dislike me. 20. I could not get “going.” 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 28 APPENDIX B Pet Attitude Scale Read each statement and then circle the number, using the response choices listed below, that corresponds with how you generally feel towards pets. 1= 2= 3= 4= 5= 6= 7= Strongly disagree Disagree Somewhat disagree Neutral Somewhat agree Agree Strongly Agree 1. I really like seeing pets enjoy their food. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 2. My pet means more to me than any of my friends. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 3. I would like a pet in my home. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4. Having pets is a waste of money. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 5. Housepets add happiness to my life (or would if I had one). 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 6. I feel that pets should always be kept outside. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 7. I spend time every day playing with my pet (or would if I had one). 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8. I have occasionally communicated with a pet and understood what it was trying to express. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 9. The world would be a better place if people would stop spending so much time caring for their pets and started caring more for other human beings instead. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 10. I like to feed animals out of my hand. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 11. I love pets. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 12. Animals belong in the wild or zoos, but not in the home. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 13. If you keep pets in the house you can expect a lot of damage to furniture. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 14. I like housepets. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 15. Pets are fun but it’s not worth the trouble of owning one. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 16. I frequently talk to my pet. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 17. I hate animals. 18. You should treat your housepets with as much respect as you would a human member of your family. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 29 APPENDIX C Participation Scale In this study, the animal-assisted activity involves volunteers brining in a trained dog for either a one-on-one visit or a group visit. Please address the following questions in terms of your participation in an animalassisted activity program. 1= Strongly disagree 2= Disagree 3= Somewhat disagree 4= Neutral 1. I am interested in participating in an animal-assisted activity program. 2. I am interested in receiving more information about animal-assisted activities. 3. I would enroll in an animal-assisted activity program. 4. I would like to visit with animals through an animalassisted activity program. 6= Agree 5= Somewhat agree 7= Strongly Agree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 30 REFERENCES Áegis of Carmichael Home Page. Retrieved March 26, 2010 from www.seniorsforliving.com. Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1989). Attachment beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44, 709-716. Al-Fayez, G., Awadalla, A., Templer, D.I., & Arikawa,H. (2003). Companion animal attitude and its family pattern in Kuwait. Society & Animals, 11 (1), 17-28. Allen, K., Shykoff, B. E., & Izzo, J. L. (2001). Pet ownership, but not ACE inhibitor therapy, blunts home blood pressure responses to mental stress. Hypertension, 38, 815-820. Allen, K. (2003). Are pets a healthy pleasure? The influence of pets on blood pressure. American Psychological Society, 12, 145-156. American Veterinary Medical Association. (2009). US pet ownership and demographic sourcebook (2007 edition). Retrieved October 18, 2009, from www.avma.org/reference/marketstats/sourcebook.asp Anderson, W. P., Reid, C. N., & Jennings, G. L. (1992). Pet ownership and risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Medical Journal of Australia, 157, 293-301. Antonucci, T. C., & Jackson, J. S. (1987). Social support, interpersonal efficacy, and health: A life course perspective. In L. L. Carstensen & B. A. Edelstein (Eds.), Handbook of clinical gerontology. Pergamon general psychology series. 146, 291-311. New York : Pergamon Press. Arden Hills Care Home Home Page. (2009). Retrieved November 14, 2009 from www.ardenhillscarehome.com. Barker,S. B., Knisely, J.S., McCain, N.L., Shubert, C.M., & Pandurangi, A.K. (2010). Exploratory study of stress-buffering response patterns from interaction with a therapy dog. Anthrozoös, 23,(1), 79-91. 31 Baun, M., Johnson, R., & McCabe, B. (2006). Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice (2nd ed.)( Fine, A.H. Ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Beck, L., & Mandresh, E. (2008). Romantic partners and four-legged friends: An extension of attachment theory to relationships with pets. Anthrozoös, 21(1), 43-56. Bernstein, P.L., Friedmann, E., & Malaspina, A. (2000). Animal-assisted therapy enhances resident social interaction and initiation in long-term care facilities. Anthrozoös, 13, 213223. Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. New York: Basic Books. Bowlby, J. (1979/1994). The Making and Breaking of Affectional Bonds. London: Tavistock Publications Limited. Brown, J. M. (2000). Childhood attachment to a companion animal and social development of incarcerated male juvenile delinquents (Doctoral dissertation, California School of Professional Psychology- Fresno, 2000). Dissertation Abstracts International, 60, 5809. Carlton Plaza Senior Living Communities Home Page. (2009). Retrieved October, 18, 2009, from www.carltonseniorliving.com. Colby, P.M., & Sherman, A. (2002). Attachment styles impact on pet visitation effectiveness. Anthrozoös, 15(2), 150-165. Collins, D. M., Fitzgerald, S. G., Sachs-Ericsson, N., Scherer, M., Cooper, R. A., & Boninger, M.L. (2006). Psychological well-being and community participation of service dog partners. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 1 (1-2), 41-48. Cowles, K. U. (1985). The death of a pet: Human responses in the breaking of a bond. In M. B. Sussman (Ed.), Pets and Family (pp. 135-148). New York: Hawthorne Press. 32 Cummings, S. M. (2002). Predictors of psychological well-being among assisted-living residents. Health and Social Work, 27(4), 293-302. Cusack, O. (1988). Pets and mental health. New York: Hawthorn Press. Delta Society. Animal-assisted activities/therapy 101. (n.d). Retrieved on October 18, 2009 from www.deltasociety.org/Page.aspx?pid=317 Dembicki, D., & Anderson, J. (1996). Pet ownership may be a factor in improved health of the elderly.Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly, 15(3), 15-31. Edwards, T. (2009). Census bureau reports world’s older population is projected to triple by 2050. Retrieved February 22, 2010, from www.census.gov/Press-release/www/releases/ archives/international_population/013882.html. Francis, G. M. (1991). “Here come the puppies”: The power of the human-animal bond. Holistic Nursing Practice, 5(2), 38-41. Friedmann, E., Katcher, A., Lynch, J., & Thomas, S. (1980). Animal companions and a one-year survival of patients after discharge from a coronary care unit. Public Health Reports, 95(4), 307-312. Friedmann, E. (1990). The value of pets for health and recovery. In Proceedings for the Waltham Symposium 20: Pets, Benefits, and Practice, 8-17, I. H. Burger (Ed.). BVA Publications. Garrity, T.F., Stallones, L., Marx, M.B., & Johnson, T.P. (1989). Pet ownership and attachment as supportive factors in the health of the elderly. Anthrozoös, 3, 35-44. Gilbey, A., McNicholas, J., & Collis, G.M. (2007). A longitudinal test of the belief that companion animal ownership can help reduce loneliness. Anthrozoös, 20(4), 345-353. Hama, H., Yogo, M., & Matsuyama, Y. (1996). Effects of stroking horses on both humans’ and horses’ heart rate responses. Japanese Psychological Research, 38, 66-73. 33 Herzog, H.A. (2007). Gender differences in human-animal interactions: A review. Anthrozoös, 20(1), 7-21. Jenkins, J.L. (1986). Psychological effects of petting a companion animal. Psychological Reports, 58, 21-22. Kahana, E., Liang, J., & Felton, B. (1980). Alternative models of person-environment fit: Prediction of morale in three homes for the aged. Journal of Gerontology, 35, 584-595. Kawamura, M., Niiyama, M., & Niiyama, H. (2007). Long-term evaluation of animal-assisted therapy for institutionalized elderly people: a preliminary result. Psychogeriatrics, 7, 813. Lawton, M.P. (1983). Time, Space, and Activity. In G.D. Rowles & R.J. Oh (Eds.) Aging and milieu: Environmental perspectives on growing old. 41-26. New York: Academic Press. Le Roux, M.C., & Kemp,R. (2009). Effect of a companion dog on depression and anxiety levels of elderly residents in a long-term care facility. Psychogeriatrics, 9, 23-26. Mannell, R. C. (1980). Social psychological techniques and strategies for studying leisure experiences. In S. E. Iso-Ahola (Ed.), Social psychological perspectives on leisure and recreation. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas. Marks, S. G., Koepke, J. E., & Bradley, C.L. (1994). Pet attachment and generativity among young adults. The Journal of Psychology, 128(6), 641-650. Maynard, M. (1974). Three theoretical aging frames of references: Implications for a rehabilitation counselor’s model. The Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 5(4), 207-214. Maynard, M. (1986). An experimental learning approach: Utilizing historical interview and occupational inventory. Physical and Occupational Therapy Geriatrics, 5 (2), 51-59. 34 McGuire, B. (1983). Constraints on leisure involvement in the later years. Activities, Adaptation, and Aging, 3, 17-24. Melson, G. F. (1990). Studying children’s attachment to their pets: A conceptual and methodological review. Anthrozoös, 4(2), 91-99. Miller, S. C., Kennedy, C., DeVoe, D., Hickey, M., Nelson, T., & Kogan, L. (2009). An examination of changes in oxytocin levels in men and women before and after interaction with a bonded dog. Anthrozoös, 22(1), 31-43. Motomura, N., Yagi, T., & Ohyama, H. (2004). Animal assisted therapy for people with dementia. Psychogeriatrics, 4, 40-42. Muschel, I. (1984). Pet therapy with terminal cancer patients. Social Casework, 65, 451-458. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Home Page. (n.d,). Retrieved February 24, 2010 from www. nimh.nih.gov/index.shtml. Pachana, N. A., Ford, J. H., Andrew, B., & Dobson, A. J. (2005). Relations between companion animals and self-reported health in older women: Cause, effect, or artifact? International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 12 (2), 103-110. Planchon, L. A., & Templer, D. I. (1996). Correlates of grief after death of a pet. Anthrozoös, 9, 107-113. Planchon, L. A., Templer,D. I., Stokes, S., & Keller, J. (2002). Bereavement experience following the death of a companion cat or dog. Society and Animals, 10, 94-105. Prato-Previde, E., Fallani, G., & Valsecchi, P. (2006). Gender differences in owners interacting with pet dogs: An observational study. Ethology, 112(1), 64-73. Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A new self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 3, 385-401. 35 Risley-Curtiss C., Holley, L. C., & Wolf, S. (2006). The animal-human bond and ethnic diversity. Social Work, 51(3), 257-267. Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20-40. Rynearson, E. K., (1978). Humans and pets and attachment. British Journal of Psychiatry, 133, 550-555. Sable, P. (1995). Pets, attachment, and well-being across the life cycle. Social Work, 40(3), 334341. Sachs-Ericsson, N., Hansen, N., & Fitzgerald, S. (2002). Benefits of assistance dogs: A review. Rehabilitation Psychology, 47(3), 251-277. Seeman, T., Singer, B., Rowe, J., Horwitz, R., and McEwen, B. S. (1997). The price of adaption: Allostatic load and its health consequences. Arch. Intern. Med. 157, 2259-2268. Serpell,J. A., Kruger, K. A., Katcher, A. H., Beck, A. M., McNicholas, J., Collis, G., et al. (2006). Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice (2nd ed.)(Fine, A. H. Ed.) San Diego, California: Academic Press. Siegel, J. M. (1990). Stressful life events and use of physician services among the elderly: The moderating role of pet ownership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 1081-1086. Souter, A., & Miller, M. (2007). Do animal-assisted activities effectively treat depression? A meta analysis. Anthrozoös, 20(2), 167-180. Sunrise Senior Living Home Page. (2009). Retrieved November, 14, 2009 from www.sunriseseniorliving.com. Templer, D., Salter, C., Dickey, S., Baldwin, R., & Veleber, D. (1981). The construction of a pet attitude scale. The Psychological Record, 31, 343-348. 36 The Palms at Bonaventure Home Page. Retrieved March 26, 2010 from www.seniorlivinginstyle.com. Triebaenbacher, S. L. (1998). The relationship between attachment to companion animals and self-esteem: A developmental perspective. In C. C. Wilson & D. Turner (Eds.), Companion animals in human health (pp. 135-148). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. United States Congress, Special Committee on Aging. (1990). Federal implementation of OBRA 1987 nursing home reform provisions : hearing before the Special Committee on Aging, United States Senate, One Hundred First Congress, first session, Washington, DC, May 18, 1989 U.S. G.P.O. : For sale by the Supt. of Docs., Congressional Sales Office, U.S. G.P.O., Washington. Walker, J., Porter, R., & Flanders, J. (2004). Increasing practitioners’ knowledge of participation among elderly adults in senior center activities. Educational Gerontology, 30, 353-360. Weiss, K.S. (1974). The provisions of social relationships. In Z. Rubin (Ed.), Doing unto others, 17-26. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Wells, Y., & Rodi, H. (2000). Effects of pet ownership on the health and well-being of older people. Australasian Journal of Applied Gerontology. 61, 143-148. Wells,D.L. (2004). The facilitation of social interactions by domestic dogs. Anthrozoös, 17, 340352. Wells, D.L. (2007). Domestic dogs and human health: An overview. British Journal of Health Psychology, 12, 145-156. Wolfe, J. R. (1983). The use of music in a group sensory training program for regressed geriatric patients. Activities, Adaptation, and Aging, 4(1), 49-62. 37