Dealing with challenging patients

advertisement

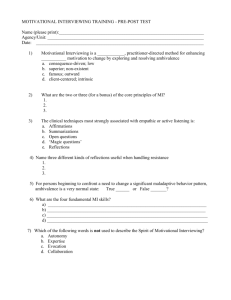

Dealing with challenging patients Communication Skills Demanding and unreasonable patients (or patients with a high IQ) Challenges: • • • • Lack of experience Emotional patients Intimidating patients Lack of background to patients’ demands • Money • Resources • Conflicting messages from other healthcare professionals What to do: • • • • • • • Nothing Document everything Senior support, second opinion Access ‘ICE’ Avoid ‘maybes’ Explain why for and not for Avoid personalising conversation What not to do: • Don’t give in to unreasonable demands • Don’t argue • Don’t lie, or blag it • Don’t offer temporary measures • Don’t put yourself in danger Patients with dementia or psychosis Challenges: • • • • • Lack of experience Lack of insight Aggression – paranoid Multiple medical problems Reliance of history from relatives • Lots of social problems, inc. alcohol and drugs • Medico-legal issues What to do: • • • • Safe environment Chaperone Low stimulus environment Excellent communication skills and patience • Non-judgemental What not to do: • Don’t ignore physical health • Don’t rush the consultation Patients with multiple or complex problems Challenges: • • • • Time limitations Spotting the red flag Satisfying the patient Lack of experience What to do: • • • • • • • • Give wiggle-room Reassure Clinical judgment Prioritise Bring back Safety net Documentation Double appointments What not to do: • Do not ignore / disregard • Do not get frustrated • Do not argue Relatives of patients Challenges: What to do: • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Different agendas Multiple people present Family feuds Emotional state Unrealistic expectations Preparation Ask the patient what they want Try to identify a point to contact Suggest a formal appointment Document conversations Keep them informed Nurse present Keep patient main focus of care Be honest and realistic What not to do: • • • • No transference / countertransference Don’t break patient confidentiality Don’t make unrealistic promises Don’t take sides Patients with personality disorders Challenges: • • • • Communication issues Consent / capacity Unpredictable Staff safety What to do: • Stay very calm • Involve Psychiatry What not to do: • Don’t confront patient Prejudiced patients Challenges: • Might not agree with treatment • May compromise their care • May think they know better What to do: • Educate them • Time to think • Offer alternative care • Remain unbiased What not to do: • React to prejudices • Take it personally Manipulative patients Challenges: What to do: • Make team members aware • They say the right things to get what they • Involve other want healthcare professionals • They have knowledge of • Negotiate the system What not to do: • Don’t confront them • Don’t pander Suicidal patients Challenges: What to do: • • • • • • • • • • • • • Defensive medicine Risk Sustaining empathy Prejudice Establishing trust D/w another medical professional Risk assessment scoring Advice from Crisis team Check previous notes Ask about protective factors Let them talk Good documentation Keep an open mind What not to do: • • • • Don’t give tips Don’t dismiss concerns Don’t be judgmental Care with prescribing DNAR (Do Not Attempt Resuscitation) patients Challenges: • • • • • • • Patient / family refusal Conflicting opinions in the team Patient not fully aware of illness Respect Experience & information Emotional / upsetting Fear of being misunderstood / passive • Balance between Guidelines and Policies and Ethics What to do: • Discuss with seniors, MDU/MPS, seniors, family, patient • Have a go • Ensure private setting / chaperone • Document properly, explain clearly, facilitate audit • Take your time, express empathy What not to do: • Don’t make decision alone • Don’t act in public • Don’t be lax with documentation Aggressive (especially drunk) patients Challenges: • Low inhibitions • Low levels of consciousness • Difficult to treat / refusals What to do: • Protocol What not to do: • Don’t rise to the bait • Don’t miss potential injuries • Don’t judge them Child patients / patients with low IQ What to do: What not to do: • Non-verbal communication • Charts, pictures, toys • Examples, e.g. on teddy • Use mother / carer • Don’t patronise • Don’t speak really slowly • Don’t use complicated language / jargon Patients who speak a different language What to do: What not to do: • Use qualified interpreters • Ask patient to summarise • Non-verbal communication • Don’t use children to translate • Don’t speak only to interpreter • Don’t use too many closed questions Patients who have difficulties in expression (e.g. dysphasia, deafness) What to do: What not to do: • Check understanding • Non-verbal communication, e.g. blinking, writing • Collateral history • Don’t rush • Don’t presume the patient is dumb Patients with communication barriers Challenges: • • • • • Misunderstandings Frustration Harder to build rapport Time – takes longer Interpreters (dilution of communication, confidentiality) • Cultural issues FY2 communication: Useful tools from the field of Psychology Dr Julie Highfield Clinical Psychologist Cardiac Rehab and Renal Services- UHCW Areas covered The following are some ideas from the field of clinical psychology which may help you when considering why some interactions with clients can be difficult. It is not intended as an exhaustive list. The kinds of things covered are: Some thoughts on why patients may struggle to adhere to your advice. This includes thinking about how patient represent illness (from Leventhal), and from psychodynamic ideas, and motivation for change (with ideas from motivational interviewing). Some thoughts on the way in which a patient may act and how this shapes our behaviour and then their behaviour in turn- drawing from Transactional analysis, reciprocal roles (CAT), and transference. To help you think about adherence • Self-efficacy: Does the patient believe in her ability to carry out the required action? How can you encourage this? • Locus of control: does the patient believe that his health is his responsibility or down to others? This affects what he would be willing to do for himself, and what he expects of you. • The representation of illness- Leventhal, next slide • Doctor-patient communication (Transactional analysis, cognitive analytical perspective- see later) • Is the experience of psychological distress impacting upon a patient’s ability to self manage? Can you ask for advice from psychology related to you area? Self-regulatory model of illness behaviour (Leventhal) Thoughts about health threat: What is it? Cause? Consequences How long for? Cure/ control Stage 1: The patient interprets their illness Emotional response to health threat: -Anger -Anxiety -Depression Stage 2:coping Style: Approach Avoidance Stage 3: Appraisal Was my coping strategy effective? Leventhal (cont) How the person interprets their illness • Identity “what do I have?” • Cause “why did this happen?” • Timeline “How long will I feel unwell?” • Treatment “What is the treatment?” • Curability “Will I be 100% well again?” • These beliefs shape illness behaviours Patients approach to chronic illness: Ideas from a psychodynamic perspective The symbolic nature of treatment: it makes me feel different (PAST negative experiences of feeling different and being treated badly for this) it controls my life (PAST negative experiences of being controlled by others) it stops me from being able to do what I would like to – (PAST experiences of restriction) it means that I will be viewed as “less” (PAST experiences of rejection and abandonment) it is another punishment (PAST experiences of abuse) Non compliance can also be a way of self-destructing, arising from hopelessness Motivational Interviewing Miller and Rollnick Motivational interviewing is a directive, client-centered counseling style for eliciting behaviour change by helping clients to explore and resolve ambivalence The specific strategies of motivational interviewing are designed to elicit, clarify, and resolve ambivalence NOT persuasion NOT advice giving BUT: 1) Open-ended questions 2) Affirmations 3) Reflective listening 4) Summaries. Principles of MI • Motivation to change is elicited from the patient, and not imposed from without. • It is the patient's task, not the doctors, to articulate and resolve his or her ambivalence. • Direct persuasion is not an effective method for resolving ambivalence. • The style is generally a quiet and eliciting one. • The doctor is directive in helping the patient to examine and resolve ambivalence. • Readiness to change is not a patient trait, but a fluctuating product of interpersonal interaction. • Emphasis on freedom of choice rather than doctor as expert Stages of Change Prochaska and DiClemente (originally 1982) produced a model of behaviour change that is used within Motivational Interviewing. Not linear, but dynamic: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Pre-contemplation: not intending to make changes Contemplation: considering a change Preparation: making small changes Action: engaging in a new behaviour Maintenance: sustaining the change over time Thus different approaches by HCPs to patients needed according to stage. The stages of change model is useful when considering poor health behaviours (e.g. smoking, drinking alcohol). A person is unlikely to take your advice and “give up” until they are ready to do so Transtheoretical Model of Change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983) Stages of change (2) • At different stages, the individual weighs up the costs and benefits in different ways. • Eg: smoking 1. Precontemplation: “I am happy to be a smoker” “Stopping smoking will make me anxious” 2. Contemplation: “I’ve been unwell, perhaps I should give up smoking” 3. Preparation: “I will cut down on smoking” 4. Action: “I have stopped smoking” 5. Maintenance: “I have stopped smoking for several months, and I feel healthier” MI style questions that may be of use • What concerns you about …. ? • What is good about the way things are at the moment? Not so good? • What would be the worst case scenario if you didn’t make any changes? • If you were going to set a goal, what would it be? • Acknowledge challenges, emphasise personal choice, build confidence based on past success Cognitive problems • Memory – Present information first – Provide specific, not general recommendations – Restrict the information to what the patient can process at the time – Organize the information e.g. by importance, time (what to do first, second), or type (benefits of treatment, side effects) – Use of oral & written information – Repeat important information: if necessary in a follow-up meeting or by providing an audio tape Considering patient interactions • Their effect upon us and how we affect them! 1. Transactional analysis 2. Reciprocal Roles (CAT) 3. Transference Transactional Analysis • Arises from Eric Berne • Interactions between people (transactions) • Within transactions, individuals adopt one of three ego states: 1. PARENT (either critical or nurturing) 2. ADULT 3. CHILD (either free child or adapted) On a ward, health care profs can find themselves becoming parental. This can mean our patients end up acting in a child ego-state. Adaptive interactions are adult-to-adult TA: ward example Patient: “There really is nothing to worry about!” parent adult child “Could you explain the procedure again? (I’m frightened)” Professional: parent adult child The patient asks an adult question, but is dismissed. The patient may then act “childishly” as a result TA: ward example (part 2) Patient: Professional: parent adult child parent “Could you explain the procedure again? (I’m frightened)” “Certainly…” adult child The patient asks an adult question, and is treated like an adult. The interaction continues in an adult-adult manor” Drama Triangle- part of Transactional Analysis If we go above and beyond the call of duty with patients, we may fall into rescuer role. Drama Triangle It is useful to be mindful of when you are rescuing. • Risks of rescuing: – End up becoming the victim through constant focus upon others, or the rescued may point the finger of blame – Risk ignoring the choices and self-efficacy of others by making decisions for them – When rescuers are burnt out they become persecutors- “getting my way” Transference and Countertransference • This will have been covered in previous teaching, but a reminder….. • In every patient interaction, health care professionals may be perceived as symbolic care givers • They may respond to us as if we are former/ current people in their lives (e.g. their mother, father, brother etc). • We may in turn respond to this. • It is helpful to be aware of how this may occur, and to not be drawn in to reacting in a non-professional manner. • The following slide on reciprocal roles will help you consider this. • For example, a person may expect that we will do everything for them, and we may be drawn in by their helplessness. Or a patient may expect that we will let them down, and will be dismissive of our treatment, which may lead us to dismiss them in return. Reciprocal Roles (CAT) patient: Team: non compliant sabotage treatment demanding “rubbish” treatment Frustrated Irritated Rejecting Cynical Critical of each other High self efficacy Internal locus of control Empowered Able to make choices Helpless Needy Stringently compliant Informing Non persecutory Clear boundaries and contract with patients Helpful but not controlling Containing Heroic Over-involved Break boundaries Help too much Foster dependence The way in which we respond affects the patient, and the patient’s response affects us. (from Ryle)