Teach First 2. - John Bald/language and literacy

advertisement

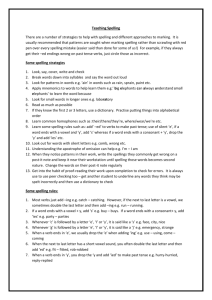

Eliminating Failure in Literacy, Languages and Basic Mathematics Part 2: Reading, Spelling, Writing and Basic Math(s). johnbald.typepad.com 1 English Spelling: Fuzzy Logic and its implications. Fuzzy Logic: A mathematical theory in which members of a set share most, but not all of its characteristics. 2 Old English (pre 1066) (Examples from D Crystal, Spell It Out 2012) cwen þe Æncglisc 3 the French Connection... table manger fruit, biscuit 4 A little German and Dr Johnson • • • Licht Haus verloren light house forlorn Ache. Dr Johnson thought it came from the Greek akhos, and “ignorant of the origins of the word” (OED) changed the spelling from ake in his dictionary. But he’s not responsible for • • • • • • • ought, bought, sought. fought, brought, thought, enough, rough, tough cough, trough bough plough thorough borough through although though dough 5 The Foundation Lesson – outline structure 1. • Wherever you can, have parent sit in. Establish a friendly atmosphere. Sit at right-angles to the child, on his/her right (this makes it easy to direct attention to any point in a text, with pencil). Ask if they find reading easy or difficult, and respond positively to any answer. If they say “don’t know”, say you’ll try to explain it so that they do. • Find out what the child does and doesn’t know. Look at reports, samples of writing, have the child read to you. If you need to, use a reading test – eg Neale Analysis – explaining to the child that you’re doing it to find out what you need to teach them. Other possible tests – British Picture Vocabulary Scale and TROG – Test for the reception of grammar – very useful for pupils with EAL. • Explain why some people find learning to read difficult – we can’t always rely on what the letters tell us. Explain how the letters work in English, as below. • Look at the letters in the child’s name, and explain any anomalies. Move to a simple text or, for young children, Ruth Miskin’s Ditties. 6 The Foundation Lesson – outline structure 2. • If a child can’t read a word, move to another word with the same pattern and teach this thoroughly, using plastic letters. Squiggle them around and have the child re-make the word. Add other words with same pattern. Once child is reading them fluently, add the word that caused the problem. Child will very often now get it right. If so, return to text. If not, repeat. • Work on the text or ditty until the child can read it fluently, then praise. At discretion, move to the next, or to spelling, or leave it there. • Keep notes of all the words you’ve worked on, and use them for memory games/flashbacks to reinforce memory. 7 Explaining fuzzy logic to children... • Do they behave themselves all of the time – or most of the time? • Is mum or dad (or teacher) in a good mood all of the time – or most of it? • The language is 1000 years old. If we were, we’d have wrinkles too. • We use what the letters tell us, but we don’t believe the letters tell us everything. 8 Fuzzy Logic: Implications for Reading. • The connection between letters and sounds is fundamental – most of the time, letters indicate a sound. • Some letters give us information about other letters – made face cycle city • We have 26 letters and over 500,000 words. Letters have to work in groups sometimes. • Because the language is so old, some parts are left over from history. Most of them are French – table, fruit, biscuit. There are patterns in these that help us to learn them. 9 Tackling reading problems – some principles • We explain English spelling as it is, in words children can easily understand. • We ask ourselves two questions: 1. What is it in this child’s thinking that is holding them up? 2. How do we help them adjust their thinking so that they can use what the letters tell them, and so read? • We base our teaching on the answer to 2. • We practise, every day. 10 Extending Reading Teaching in KS2 • Reading and language development go together. The spoken word moves quickly. The written word stands still, so we can study it. • We get to know non-fiction as well as we know fiction, and make reading a central part of learning in all subjects – Gateway School • We explain all new vocabulary, and the links between words. • We teach spoken and written language together when teaching new languages. 11 Slimmed Down Spelling 1 – what we can hear. • Most letters represent sounds. Sometimes letters work in groups, some words have an extra letter, and occasionally letters are awkward. • If we hear a sound when we say a word carefully, we need at least one letter for it. This is the phonic element in spelling, and it works around 70% of the time. 12 Slimmed Down Spelling 2 – what we need to learn. • Sometimes letters work in groups – we use a group when we’ve learned we need it, eg, station • Some words have an extra letter, eg made, chaos. We use an extra letter when we’ve learned we need it. There is usually only one in any word. • Sometimes, because of shortcuts in speech, or changes in the way people speak, the letter we need is not the one we think we need. These letters are awkward, and we only use them when we’ve learned we need them. Examples include the final a in animal, and the a after with in was, water, warm etc. 13 ...and a note on vowels. • A vowel is a sound made with the voice. Without a voice sound, we wouldn’t be able to hear the word. • Roi (king) – royal. Voix (voice) – vouielle - vowel. • We have around 24 voice sounds, and seven voice letters a e i y o u (single) w (double) • English vowel letters are often used in combination, and each can produce more than one sound. Therefore, information from vowels often has to be interpreted in the context of individual words. This is “fuzzy logic”. 14 hints... • Most spelling mistakes involve leaving a letter out – children need to learn to say words slowly and carefully when they are learning to spell them. • If a child is stuck on a word, I don’t teach that one straightaway, but go to another that has the same pattern. I return to the original word once the pattern is secure. • The four elements in Slimmed Down Spelling need to be practised, so that children have a reason for deciding to write each letter – they can either hear it, or have learned it. • If they haven’t learned a word needs an extra letter or has a pattern, they don’t use it – then they can learn that the word needs it. • We almost never learn a word without learning another that is like it. • Practice should be systematic, and gradually home in on the words a child is not sure of. • Blank playing cards make professional-looking flashcards that can be tailored to individual needs. 15 We never copy... • Jerking our eyes back and forth between the original and our own version disrupts the formation of neural connections, and makes learning slower. • Instead, we study the word, then look away and trace it on our sleeve, or write it independently on scrap paper. Once it’s right, we insert it in our writing independently, and try to make a point of using new words we’ve learned. 16 The role and training of the assistant • The government provides generic training for assistants. This needs to be made more specific at school level. • Assistants need training in the subjects in which they support the children. Where possible, assistants should work with departments, particularly MFL • All departments whose work involves literacy should contribute to the training of the assistant on their specific requirements • Assistants should be encouraged to make literacy a major part of their CPD. • Wherever possible, training for assistants should be school-based, and applied to the children the assistant works with. • Classroom Assistant’s Edufax (free, johnbald.typepad.com) has detailed guidance on training assistants. Teaching grammar - a principle, from Jerome Bruner. If one respects the ways of thought of the growing child, if one is courteous enough to translate material into his logical forms and challenging enough to tempt him to advance, then it is possible to introduce him at an early age to the ideas and styles that in later life make an educated man. (Bruner, The Process of Education 1960: 52) 21st Century Grammar • Starts from the learner’s perspective • Is based on usage, including idiom as well as rules and patterns • Enables people to communicate by putting what they want to say into the words and forms of the new language • Uses plain and short words wherever possible • Puts first things first • Understands its limitations Key Terms (traditional or linguistic vocabulary in brackets.) Note: these may be used as a transition to the terminology of national tests. • Sentence. Begins with capital, ends with full stop. • Verb. Most verbs do things or say how we are feeling. To be, To have, the most common verbs, don’t. The French call these verbs of state. The Chinese call them linking verbs. A verb may be a group of words. Verbs are so important, that they have a name. (infinitive). In English, their name begins with “to”. • Subject - not the topic of a sentence, but whoever or whatever does what the verb does (or is, or has). This takes some practice, because of the normal sense of “topic”. • Link word (conjunction, connective). • Starter word (subordinator). • Tense - old French word tens, time. In my approach, tense and time are synonymous, and we teach tense to indicate time in the new language. This is not the same as the current view of linguistics specialists. However, as the NC lists only present and past tense, not a major problem as we can talk about future time. • Noun name or type • Companion word – keep nouns company in most European languages – (aka, article, determiner) • Adjective, adverb. Tell us more about a noun or verb. • Punctuation. Helps us to organise what we say to make it clear and easy to read. Priorities – though each idea may well take time to establish. Letters and Capital Letters. Full stop after a simple sentence - making a decision rather than guessing. Compound sentences – and, but. Other extensions – adjectives, adverbs. Further link words. Menu system – every meal is not a banquet. Adding new clauses to the “main course”. An analogy from a parent on sentence construction – eating out. • Main course. Subject + verb. • Starter + main (include starter word or phrase – usually time) • Main + dessert (include a link word or strong punctuation - ; :) • Starter, main + dessert. • Longer sentences – aperitif, coffee, cheese, liqueurs...Christmas dinner? Time Zones • Linguistics: tense is indicated by a change verb form - I go, I went. They use “aspect” to describe other ways of marking time – eg He leaves tomorrow. • All other European languages use their word for time to describe tense. • To develop an understanding of tense, we need to develop a sense of time. Read aloud – discuss – have pupils say whether things sound right and why. • Tense is then a matter of conscious control. Principles of Teaching Handwriting • Explain that we can never write as quickly as we can think. • Decide on a consistent way of forming letters, and stick to it. Beware Marion Richardson f. • Include exit strokes – if you don’t, children press hard at the end of the downstroke, making it harder to move to joining. • Watch the child write – do they start each letter in the right place? • Have a range of guidelines to use as appropriate. • Avoid biros – their ink is oil-based. French lined paper – “grands carreaux” Same pupil after one year. Ros Wilson and Alan Peat: Putting Children in Control. Building and Using Neural Networks in Basic Mathematics: Four key questions. • What does the child already know? • What does he or she need to know next? • How do we explain it? • How do we have the child practise it? Some Principles Do not introduce too many new concepts at once. With slower learners, one at a time. Combine concepts only once they are secure. Addition bonds singly rather than in groups, building from the bottom up. Do not introduce subtraction bonds until single figure additions are fully in place. Move from addition and subtraction to multiplication via tables. Teach 2x table carefully, and use as a template for the others, in numerical sequence. Resources. Numicon builds a sense of numbers greater than one as units. Playing cards can be used to speed up instant recall of combinations that have been learned. Blank playing cards (Amazon, £15 per 1000). Multiple uses, including Pelmanism. Maths internet sites, including Khan Academy References Grammatical Terms and Language Learning; A Personal View. J. Bald, Scottish Languages Review 20, 1,6, November 2009. Fernald, GM. Remedial Techniques in Basic School Subjects. McGrawHill, 1943 (via Bookfinder.com. Original version has case studies). Hancock, J. How to Improve Your Memory for Study. Pearson