Volume XXXIX - Royal Asiatic Society

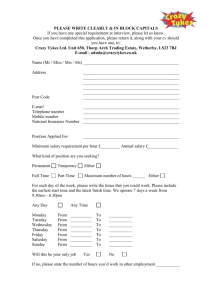

advertisement