TPP good - Open Evidence Project

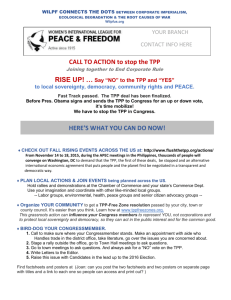

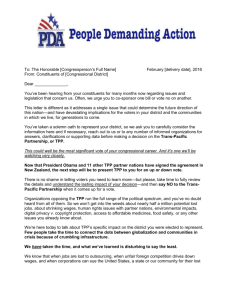

advertisement