TS720 Cowell Reflective Inquiry Presentation

advertisement

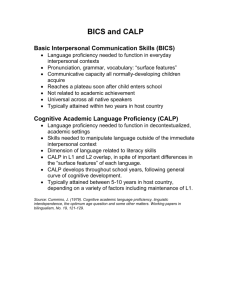

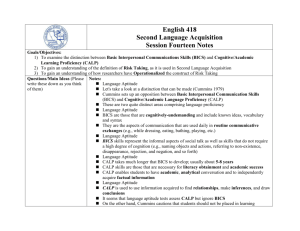

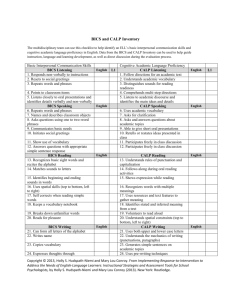

An oral and conceptual framework for L2 academic language development HANNAH COWELL MATESOL CANDIDATE EMPORIA STATE UNIVERSITY Introduction and Abstract 2 Abstract: This presentation provides a critical and sociocultural framework to understand L2 social language proficiency’s role in L2 academic language development. This topic pertains to adult or adolescent English learners of limited literacy and/or academic language competence in their L1. Participants will gain insight into oral language development strategies which will develop academic language and conceptual thought in the L2. Blueprint: Where are we going? 3 Introduction and abstract The achievement gap & a literature gap My research questions My background and personal interest in the topic Distinguish between different types of language Relationship between L1 and L2 cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP) My conceptual framework for understanding and teaching CALP The role oral language plays in academic development through vocabulary, structures, and instructional/corrective techniques Pedagogical implications for language teachers, including linguistic, metacognitive and oral language strategies References Future research and conclusion Contact information A gap in the literature on the achievement gap 4 Achievement gap between English Learners (ELs) and monolingual English-speaking peers in academic areas is well documented ELs often seem to be proficient in English yet the gap in reading, math, and other academic content areas generally worsens over time instead of improving (Cummins, 1982, 1984) General academic proficiency represents access to higher education, gainful employment, etc. (Cummins, 2012) Low L1 literacy students may come from a culture where print literacy is not part of the process of socialization but oral literacy is Bias toward developing academic proficiency through reading and writing, not speaking and listening (Soto-Hinman, 2011) Studies have traditionally focused on positive academic language transfer among students who were literate and/or had some formal schooling in their L1 (Bigelow, Delmas, Hansen, & Tarone, 2006) Framing my research questions In this presentation I will propose a critical, conceptual, and culturally sensitive framework through which to explore these questions: 1. What are the necessary components of English CALP and how can learners with low L1 literacy acquire them? 2. How can L2 oral language development and fluency promote the development of L2 CALP? My background and why I care 6 My background and personal interest 7 Story telling and oral literacy but little value for/access to print Need for academic language in jobs, educational opportunities Widespread use of communicative techniques in EFL classes How could I teach academic language effectively so my students could read and write proficiently in English? Limited research on CALP related to these types of students Reading and writing (which may be initially out of reach for these learners) often emphasized as THE way to develop CALP, particularly in my SLA textbooks and even occasionally my methods book CALP (as defined in its broadest sense) is a social, economic, academic, and employment gateway—it must be accessible to all learners! Cummins’ (1982) different types of language 8 BICS CALP Basic Interpersonal Cognitive Academic Communication Skills Used in social and casual interactions “Playground language” Acquired in 1-2 years Context-embedded Cognitively undemanding Associated with listening and speaking Language Proficiency Used in formal and school settings Underlying proficiency needed for academic success Acquired in 5-7 years Context-reduced Cognitively demanding Associated with reading and writing 9 Cummins’ Framework for BICS/CALP Four quadrants: Quadrant 1: Cognitively undemanding + context-embedded Quadrant 2: Cognitively undemanding + context-reduced Quadrant 3: Cognitively demanding + context-embedded Quadrant 4: Cognitively demanding + context-reduced Taken from Roessingh (2006) 10 The four quadrants of BICS/CALP 1. “Here and now” 2. “My lived experience” 3. “There and then” 4. Metaphoric competence Taken from Roessingh (2006) 11 BICS, CALP, CUP – the acronyms keep Cummin’ Cummins (1984) proposed a “Common Underlying Proficiency” or CUP between L1 & L2 Potential for CALP cross-linguistic transfer CUP addresses relationship between language and thought Also called the “Interdependence Hypothesis” Ideal representation of Common Underlying Proficiency (CUP) between L1 and L2 Taken from Roessingh (2003) Metacognition and CALP 12 Directing attention Metaphorical & symbolic Setting goals Abstract concepts Exploring multiple Complex relationships meanings Making inferences Drawing conclusions Evaluating information Synthesizing information Comparing/contrasting Persuading Relates thought to language Using learning strategies Applying prior knowledge Linguistic transfer strategies Pragmatic, Strategic, Discourse competences A critical and sociocultural framework for understanding CALP 13 CALP = specialized vocab + complex syntactic structures? CALP is more than the sum of its linguistic parts It is academic language + cognitive proficiency (Roessingh, 2003) Don’t forget about Vygosky: Language + verbal thought (Bylund, 2011) Self-regulatory and metacognitive processes Discourse types and literacies vary across cultures (Saville-Troike, 2007) Dynamic, socioculturally and educationally-mediated process Even cognitive abilities are socioculturally mediated! (Example of oral literacy) (Aukerman, 2007) All meaningful language has a context (Aukerman, 2007) Expand ability in identifying, creating & expanding (para)linguistic contexts Re-contextualization of familiar social forms as academic metaphors Oral Language and CALP: Dialogical possibilities 14 CALP is not merely linguistic structure, but vocab and syntax are crucial in academic development (Saville-Troike, 2007) L2 Oral fluency creates automaticity of processing (freeing up mental resources for metacognition) Some learners are more comfortable learning through the oral medium Oral language and “academic talk” can provide scaffolding for CALP development (Soto-Hinman, 2011) Output elicited from ELs tends to be BICS rather than CALPoriented Oral language can support vocabulary, academic structure & syntax when appropriate instructional and corrective techniques are used Oral Language: Vocabulary 15 o Acquiring a word for recognition and automatic retrieval o o o o o requires multiple meaningful encounters (Saville-Troike, 2007) Enough encounters are not likely to be garnered through reading alone To decipher a word from context clues, the reader must understand 95% of the other words in the text ELs have a significant vocabulary gap when compared with monolingual English speaking peers BICS-type speech only requires about 2,000 words, while CALPoriented speech can require 20,000 words or more (Roessingh, 2006) Oral structured practice can provide the extra support ELs need to close this gap Oral Language: Structures 16 o The most troubling language for ELs tends to be figurative o o o o o and idiomatic language (idioms, phrasal verbs, formulaic sequences) (Guduru, 2011) These structures often represent cognitive processes, complex relationships, and abstract concepts Multi-word “syntagmatic” chunks are hard to decipher There is need for explicit instruction and practice in a medium that students feel naturally comfortable with, i.e. oral language Cooperative learning of these forms promotes self-analysis and reflection on meaning and metaphor Students with low L1 literacy may rely more on semantic processing rather than morphosyntactic awareness Oral Language: Classroom Methods 17 Instructional Techniques o Explicit instruction! o Cooperative learning o Engage with texts through oral language o Negotiate meaning through interaction o Recognize students’ unique abilities such as semantic processing, memorization, and strategic competence Corrective Techniques o Direct metalinguistic feedback o Create awareness when using recasting o Focus on errors that DO NOT impede meaning – these are most likely to fossilize o Repeat, repeat, repeat and be patient! CALP Summary & Model 18 Automaticity of processing Socioculturally and educationally-mediated Content-area vocab, passive voice, subordinates, relative clauses, etc. Specialized vocab and complex syntax Idioms, cohesive ties, logical connectors, discourse markers, formulaic sequences Figurative language & metalinguistic messages Summarize, infer, compare, evaluate, conclude, selfregulation strategies Metacognition, abstract thought, and metaphorical relationships Linguistic CALP: Pedagogical Implications 19 Explicit instruction of specialized, content-area vocab and complex syntactical structures Use collocations by grouping words together; create semantic maps and group vocabulary meaningfully Create dual-language projects/presentations (Cummins, 2012) Allow for translation/clarification in the L1 Model and structure output of formulaic language such as cohesive ties, logical connectors, discourse markers Give explicit corrective feedback especially regarding errors that do not impede meaning Use non-verbal cues to signal correction through recasting (Saville-Troike, 2007) Metacognitive CALP: Pedagogical Implications 20 Teach substantiating thoughts from a text Assign roles of summarizing, questioning, predicting, analyzing, and connecting within group work (Guduru, 2011) Show students how to paraphrase and guess from contextual clues; this can lead to self-reflection Teach language, learning, and transference strategies explicitly Make use of thematic units which activate prior knowledge Encourage peer response and peer editing groups (after extensive and structured modeling) Model questioning and peer response techniques to elicit more elaborate responses Oral Language: Pedagogical Implications 21 Scaffold students’ oral production through repetition, paraphrasing, expansion, elaboration, sentence completion, substitution frames, vertical construction, and comprehension checks (Saville-Troike, 2007) Shadow an EL to assess their use and comprehension of “academic talk” (Soto-Hinman, 2011) Model and demonstrate genuine questioning Cooperative techniques such as “think-pair-share” Use techniques that promote fluency & automatic processing such as rehearsal, repetition, consciousnessraising, and use of formulaic sequences and discourse markers References 22 Aukerman, M. (2007). A culpable CALP: Rethinking the conversational/academic language proficiency distinction in early literacy instruction. The Reading Teacher, 60(7), 626-635. doi: 10.1598/RT.60.7.3 Bigelow, M., Delmas, R., Hansen, K., & Tarone, E. (2006). Literacy and the processing of oral recasts in SLA. TESOL Quarterly, 40(4), 665-689. Stable url: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40264303 Bylund, J. (2011). Thought and second language: A Vygotskian framework for understanding BICS and CALP. Communiqué, 39(5), 4-6. Cummins, J. (1982). Bilingualism and minority language children. Toronto, ON: OISE Press. Cummins, J. (1984). Bilingualism and special education: Issues in assessment and pedagogy. London: Multilingual Matters. Cummins, J. (2012). The intersection of cognitive and sociocultural factors in the development of reading comprehension among immigrant students. Reading and Writing, 25(8), 1973-1990. doi: 10.1007/s11145-010-9290-7 Guduru, R. K. (2011). Enhancing ESL learners’ idiom competence: Bridging the gap between BICS and CALP. International Journal of Social Sciences and Education, 1(4), 540-556. Lightbrown, P. M. & Spada, N. (2011). How languages are learned. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Roessingh, H. (2006). BICS-CALP: An introduction for some, a review for others. TESL Canada Journal, 2, 91-96. Saville-Troike, M. (2007). Introducing second language acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Soto-Hinman, I. (2011). Increasing academic oral language development using English language learner shadowing in classrooms. Multicultural Education, 18(2), 20-23. Future Research & Conclusion 23 Lastly, further research is needed, particularly in the area of L1-L2 CALP transfer in L1 illiterate or low L1 literacy learners (Bigelow, Delmas, Hansen, & Tarone, 2006). This population is often understudied yet needs access to CALP just as much as more literate students. Remember the importance of explicit instruction in the area of CALP whether using the oral or print medium. Good teaching does not happen by accident and students cannot run unless we teach them to crawl first. 24 Please feel free to contact me! hcowell@g.emporia.edu 785-383-5177 Hannah Cowell Emporia State University TESOL Program, Box 4023 Department of IDT TESOL 1200 Commercial St Emporia, KS 66801 To view a voice-embedded form of this presentation, please visit http://www.youtube.com/watch?v= 5Cyc83bTGDw&feature=youtu.be