A Philosophy of Language Instruction in High School Robert Harrell

advertisement

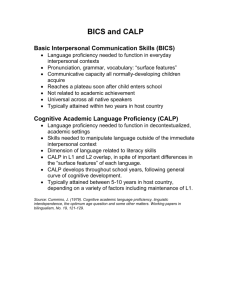

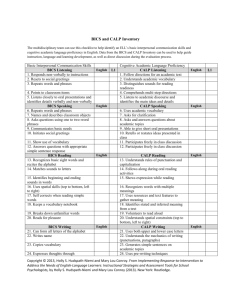

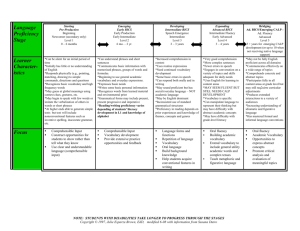

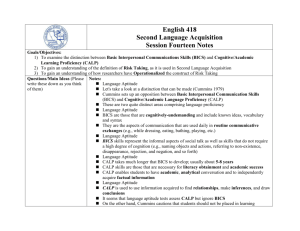

A Philosophy of Language Instruction in High School Robert Harrell In developing and articulating a philosophy of language instruction, or instruction of any kind for that matter, a good place to start is at the end. What is the goal of our instruction? What should students be able to do: recall a set of fact? Apply those facts to a given situation? Analyze a text, whether written, oral, visual, or audiovisual using critical thinking skills? Synthesize the learned material and create something entirely new? Foreign language instruction has – or should have – the latter as its goal: giving students the tools they need to create something entirely new, the expression of their own thoughts, questions, and desires in another language. This is thinking of the highest order because it is not simply the recitation of learned phrases but the manipulation and synthesis of acquired elements into something new and uniquely suited to accomplishing the task of eliciting or expressing information about knowledge, will, hopes, desires, etc. In other words, the goal of Foreign Language instruction is communication. For the high school setting, further refinement of the goal is necessary. What sort of communication do we want to see? In English Language Arts, Science, Math, and History courses, the emphasis is on the acquisition of Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP), that is, not only the vocabulary specific to the discipline but also the standard grammar, syntax, and vocabulary of academic discourse. Should this also be the goal of Foreign Language instruction? Before answering the question, we need to remember that students, for the most part, are learning the academic register of a language they already know. The course of instruction is designed for students who already speak the language of instruction fluently. Modifications and accommodations must take place for those who are not already fluent so that they can take part in the course. In the typical high school curriculum, learners of a foreign language are beginning from a base of zero knowledge. They are conversant with neither the course content nor the language of instruction. (See the ACTFL position statement on 90%+ use of the target language both inside and outside the classroom). This is radically different from all other courses except English Language Development (ELD). If a district had a fully articulated program of foreign language instruction from kindergarten through grade twelve (vid. World Language Standards for California Public Schools), the situation would be similar to that of other disciplines, but most districts do not, and the situation is not. Many administrators and teachers fail to recognize that tens to hundreds of thousands of hours of language acquisition through Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS) precede the introduction of Academic Language in school. As a result, they think erroneously that the same content and standards that apply in other subjects ought to apply in foreign language instruction. This thinking is, however, fallacious because it does not acknowledge the necessity of developing BICS before addressing CALP. Another factor that ought to influence curriculum design (also known as Scope and Sequence), but often does not, is the goal or goals of the learner(s). Other disciplines in high school rightly place an emphasis on CALP in preparation of pursuing study of the subjects at university. Most students have further study as one of their goals. Once again the situation is different for foreign language. Students will most likely use the target language, if they use it at all, for traveling, meeting tourists, speaking to clients or tradesmen, conversing with acquaintances. They will need some specialized vocabulary, depending upon the task at hand, but not academic language. Only a small percentage will continue with language study as an academic pursuit. Some very good reasons, then, to concentrate on helping students acquire Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills are the following: 1. BICS is foundational, and we need to lay a solid foundation before we attempt to build a superstructure, no matter how attractive. Otherwise we are building on sand, and the edifice will collapse when faced with real-life communication. 2. BICS is not only foundational but pervasive. Even when communicating in the rarified atmosphere of academia, the ability to maintain Interpersonal Communication is essential. 3. It is impossible to address all of the contexts and situation in which our students will or may employ the target language. Therefore we must equip them with basic skills that allow them to communicate interpersonally, thereby providing them with the means to acquire the specialized vocabulary, grammar, and syntax of their chosen domain when they need it. 4. Since the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few or the one, our instruction should address primarily the goals and uses of the overwhelming majority (dare I say 96%?) of our students*. This will be essential basic human interpersonal communication: introductions, simple requests and replies, giving and getting personal information, expressing opinions on familiar topics, etc. All of this falls naturally under the rubric of BICS. For these reasons and more, I unashamedly and unabashedly choose to expend my resources and spend my time and energy on Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills rather than Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency. *We do not ignore the needs and interests of the minority but neither do we emphasize them. There is room in instruction to address the needs of the few and the one without sacrificing the needs of the many. Instead of leaving large numbers of students behind each year, we bring the majority along to greater fluency while providing the few with the means and opportunities to go beyond and above. Legacy programs have tended to cater to an “elite” few while sacrificing the many.