document

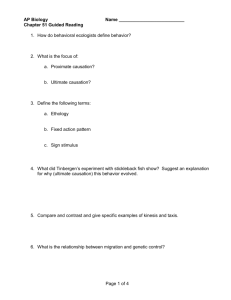

TORTS LECTURE 7

CAUSATION & DAMAGE

PARTICULAR DUTY AREAS

(a) Products Liability

(b) Defective Structures

(c) Nervous Shock

Damage in Negligence

Negligence

Duty of care

Breach

Damage

Damage in Negligence

Negligence

Duty of care

Breach

Damage

Damage in Negligence

• Damage is the gist of the action in Negligence

• The scope of actionable damage:

– property

– personal

– mental

– pure economic loss

• Damage must be actual for compensation; no cause of action accrues until damage

• Limitations period therefore begin from the time of the injurious consequences of a conduct not from when the conduct first occurred

Damage in Negligence

• For P to be successful in an action in

Negligence, D’s breach of duty must cause damage to P or his/her property

CAUSATION

Duty of Care breach causation damage

= Negligence

There must be a causal link between D’s breach of duty and damage to P or P’s property

CAUSATION: THE ELEMENTS

• Causation involves two fundamental questions:

– the factual question whether D’s act in fact caused P’s damage: causation-in-fact

– Whether, and to what extent D should be held responsible for the consequences of his conduct: legal causation

CAUSATION-IN-FACT

• Causation in fact relates to the factor(s) or conditions which were causally relevant in producing the consequences

• Whether a particular condition is sufficient to be causally relevant depends on whether it was a necessary condition for the occurrence of the damage

• The necessary condition: causa sine qua non

CAUSATION

• To be successful in a claim for a remedy, P needs to prove that the loss for which he/she seeks compensation was caused in fact by the D’s wrongful act

• Traditionally, the test whether D’s wrongful act did in fact cause the loss is the ‘but for’ test

THE ‘BUT FOR’ TEST

• But for the D’s conduct, the injury to P would not have happened:

–

Waller v James (Wrongful life)

THE FUNCTION OF THE ‘BUT

FOR’ TEST

• Two functions:

– The primary (negative) function is to assist in eliminating factors which made no difference to the outcome

– The second (positive) function: it helps to identify a condition or a factor which may itself then be subject to a test of legal causation

THE ‘BUT FOR’ TEST IN THE

HIGH COURT

• Fitzgerald v Penn ( 1954) 91 CLR 268

– ‘Causation is all ultimately a matter of common sense….[It] is not susceptible of reduction to a satisfactory formula’(per Dixon,

Fullagar and Kitto JJ)

•

March v E& MH Stramare (1991) 171 CLR 506* The but for test gives rise to a well known difficulty in cases where there are two or more acts or events which would each be sufficient to bring about the plaintiffs injury. The application of the tests gives the results, contrary to common sense, that neither is a cause. The application of the tests proves to be either inadequate or troublesome in various situations in which there are multiple acts or events leading to the plaintiff's injury (per Mason J)

THE ‘BUT FOR’ TEST: IMPLICATIONS

OF A COMMON SENSE APPROACH

• Bennett v Minister of Community Welfare (1992) 176 408

– ‘ if the but for test is applied in a practical common sense way, it enables the tribunal of fact, consciously or unconsciously, to give effect to value judgments concerning responsibility for the damage. If ..the test is applied in that way, it gives the tribunal an unfettered discretion to ignore a condition or relation which was in fact a precondition of the occurrence of the damages’

THE ‘BUT FOR’ TEST IS NOT

EXHAUSTIVE

• Bennett: ‘ causation is essentially a question of fact to be resolved as a matter of common sense.

In resolving that question, the ‘but for’ test , applied as a negative criterion of causation, has an important role to play but it is not a comprehensive and exhaustive test of causation; value judgments and policy considerations necessarily intrude (per Mason CJ , Deane and

Toohey JJ)

MULTIPLE CAUSES

• Where the injury or damage of which the plaintiff complains is caused by D’s act combined with some other act or event, D is liable for the whole of the loss where it is indivisible; where it is divisible, D is liable for the proportion that is attributable to him/her

MULTIPLE CAUSES: TYPES

• Concurrent sufficient causes

– where two or more independent events cause the damage/loss to D

( eg, two separate fires destroy P’s property)

• Successive sufficient causes

Baker v Willoughby

Jobling v Associated Dairies Ltd

(dormant spondylotic myelopathy activated)

Malec v Hutton

( possible future spinal condition )

– D2 is entitled to take P (the victim) as he finds him/her

– Where D2 exacerbates a pre-existing loss/injury (such as hasten the death of P) D2 is liable only for the part of the damage that is attributable to him

THE ELEMENTS OF

CAUSATION

Causation

Factual

(Causation in fact)

Legal

THE ELEMENTS OF

CAUSATION

Causation

Factual

(Causation in fact)

Legal

LEGAL CAUSATION

• Factual causation in itself is not necessarily sufficient as a basis for D’s liability

• To be liable, D’s conduct must be the proximate cause of P’s injury

• P’s harm must not be too remote from D’s conduct

REMOTENESS

• The law cannot take account of everything that follows a wrongful act; it regards some matters as outside the scope of its selection.

In the varied wave of affairs, the law must abstract some consequences as relevant, not perhaps on grounds of pure logic but simply for practical reasons Per Lord Wright

Liebosch Dredger v SS Edison [1933] AC

449

Case Law on Remoteness

• Earlier position in Common Law

–

Re Polemis :- the ‘directness element’

• The current position:

– The Wagon Mound (No. 1)

– The Wagon Mound (No. 2)

CAUSATION - CLA Test

•

5D General principles

• (1) A determination that negligence caused particular harm comprises the following elements: (a) that the negligence was a necessary condition of the occurrence of the harm ( "factual causation"), and (b) that it is appropriate for the scope of the negligent person’s liability to extend to the harm so caused ( "scope of liability").

Section 5D “Necessary

Condition”

Woolworths Limited v Strong & Anor

[2010] NSWCA 282 (2 November 2010)

One level of the Centro Taree Shopping Centre contained 2 large retail shops separated by a common area, part of which operated as a food court. One of the large retail shops was Big W.

On 24 September 2004 at around 12:30pm Ms Strong was at the shopping centre with her friends.

Big W had an exclusive right under its lease to conduct

“sidewalk sales” within an area that was roughly square and extended 11 metres into the common area towards the food court from the frontage of the leased premises.

Woolworths Limited v Strong & Anor

[2010] NSWCA 282 (2 November 2010)

On the day in question there were two large plant stands with 3 or 4 racks on each stand in the common area outside Big W. There were pot plants on those racks. The stands themselves were about shoulder height. They were placed so as to create a corridor directly outside the

Big W store, and leading directly to that store. The stands had been in that location from around 8am that day.

Ms Strong had undergone an amputation above the right knee decades before the accident. By using crutches, she had been able to achieve a high degree of mobility. On the day in question, she and her friends were going towards Big W. They passed between the two plant stands.

The corridor created by the plant stands was wide enough for the three women to walk alongside each other.

Woolworths Limited v Strong & Anor

[2010] NSWCA 282 (2 November 2010)

Ms Strong was actively involved in keeping pot plants. She said, “I went to look at the plant stand on my right and just after I’d gone in that’s when I had my fall.”

The tip of her right crutch slipped from under her, and she fell heavily.

The trial judge accepted that there was a chip on the floor, that some grease had come from it, and that Ms Strong slipped when the end of her crutch came in contact with either the chip or the grease.

It is clear enough that the type of

“chip” involved was a french fry, rather than a potato crisp or a small detached piece of flooring. The spot where Ms Strong fell was approximately 4 metres from the entrance to the Big W.

The trial judge found that the place where Ms Strong slipped was within the area where Big W conducted “sidewalk sales” and it was within the “occupancy, care and control” of Big W.

Woolworths Limited v Strong & Anor

[2010] NSWCA 282 (2 November 2010)

• Campbell J (Handley AJA & Harrison J agreeing):

Before a court makes a finding “that negligence caused particular harm”, section 5D(1)(a) Civil Liability Act identifies, as one of the two elements that must usually be proved, “that the negligence was a necessary condition of the occurrence of the harm.” “Negligence” there has its defined meaning, arising from section 5 Civil Liability

Act , of “failure to exercise reasonable care and skill” .

The statutory test for causation thus usually requires a decision about whether failure to exercise reasonable care and skill was a necessary condition of the occurrence of the harm. … The test for causation under section 5D(1)(a) has some measure of continuity with the previous common law, because if A is a necessary condition for the occurrence of B, one can always say that B would not happen but for

A.

Woolworths Limited v Strong & Anor

[2010] NSWCA 282 (2 November 2010)

• Campbell J (Handley AJA & Harrison J agreeing)

When causation was decided according to the common law, it was held that a defendant having materially increased the risk of an injury of a particular type occurring is not the same as the defendant having materially contributed to (and thus, according to the common law, caused) a particular injury of that type that has occurred: Bendix

Mintex Pty Ltd v Barnes (1997) 42 NSWLR 307 at 316 per Mason P.

…It is only if the “necessary condition” test in section 5D(1)(a) is satisfied that there can be causation within the meaning of section

5D(1). That is because section 5D(1)(b) poses a further test (ie, that it is appropriate for the scope of the negligent person’s liability to extend to the harm so caused ), that is to be applied even if the “ necessary condition ” test is satisfied. In other words, section 5D(1)(b) operates as a means by which causation might not be found, even if the “ necessary condition ” test of section 5D(1)(a) were to be satisfied.

Woolworths Limited v Strong & Anor

[2010] NSWCA 282 (2 November 2010)

• Campbell J (Handley AJA & Harrison J agreeing)

The reasons of the [trial] judge … do not engage in a process of deciding what it was that [Big W] failed to do that the taking of reasonable care required it to do, and then whether that failure to take reasonable care was a necessary condition of the occurrence of the particular harm that

[Ms Strong] sustained.

Thus, the [trial] judge has not decided the case in the way the statute requires. ... That the chip was able to be seen after the accident says nothing about whether the presence of one or more Woolworths employees in the area …was adequate for the taking of reasonable care. To say “it should have been removed” is to express a conclusion, but not one arrived at by the type of reasoning the statute requires. ...

This Court must examine the question of causation of damage for itself.

Woolworths Limited v Strong & Anor

[2010] NSWCA 282 (2 November 2010)

• Campbell J (Handley AJA & Harrison J agreeing)

In circumstances where [Big W] had no relevant cleaning system at all, it is easy to conclude that it breached its duty of care to [Ms Strong].

However, it is not possible to decide whether the breach of duty was a necessary condition of the particular harm without giving consideration to what the minimum content of the obligation to take reasonable care to prevent patrons from slipping would have been. …

The present is not, however, a case in which proof of breach of duty in itself makes likely that, had the duty been performed, the damage would not have been caused. That is because there is no evidence that would justify a conclusion that taking reasonable care, in the present case, required the continuous presence of someone always on the lookout for potential slippery substances. Periodical inspections and cleanings were all that reasonable care required.

Woolworths Limited v Strong & Anor

[2010] NSWCA 282 (2 November 2010)

…In my view, there is no basis for concluding, in the present case, that the chip had been on the ground for long enough for it to be detected and removed by the operation of a reasonable cleaning system. There was no evidence of there being anything about the physical appearance of the chip, such as it being dirty, that might provide the ground for an inference that it had been there for some time. … There was no basis for concluding that the chip could have been dropped at any time of the day, or at least for concluding that it was more likely than not that it was not dropped comparatively soon before the First Respondent slipped. There was no basis for inferring whether the “grease stain” was something that had spontaneously oozed from the chip as it lay on the ground, or had fallen with it (in either case existing and being visible before the fall), rather than that it had been squeezed out of the chip as the crutch compressed and moved it. …

Woolworths Limited v Strong & Anor

[2010] NSWCA 282 (2 November 2010)

There was no evidence concerning the temperature of the chip from any other witness. The fact that the cleaning contractor engaged a second cleaner, with special duties that included (but were not confined to) attending to the food court area from 11:00am to 2:00pm provides some basis for believing that there was an increased risk of things being dropped in that area during the time period. The site of the accident was very close to the food court. The time the accident occurred, at 12:30pm, fits comfortably within the range of time at which people ordinarily eat lunch. …However, that fact does not assist in concluding how long it was likely to have been there.

There was no evidence on the basis of which a judge could conclude that the taking of reasonable care to prevent physical injury to people within the sidewalk sales area involved any higher degree of diligence or vigilance than was applied immediately outside the perimeter of the sidewalk sales area. …

Woolworths Limited v Strong & Anor

[2010] NSWCA 282 (2 November 2010)

• Campbell J (Handley AJA & Harrison J agreeing)

In the present case, if one were to ask whether the First

Respondent would not have been injured if the Appellant had in place a reasonable system for detecting and removing potentially slippery substances, one can answer

“maybe” . In my view the evidence does not enable the answer “more likely than not” to be given. In the circumstances, the First Respondent did not establish causation of damage.

INTERVENING ACT

• An intervening act breaks the chain of causation and may relieve D of liability. To be sufficient to break the chain, it must either be a:

– human action that is properly to be regarded as voluntary or a causally independent event the conjunction of which with the wrongful act in or omission is by ordinary standards so extremely unlikely as to be turned a coincidence ( Smith J

Haber v Walker [1963] VR 339

INTERVENING ACT

• A foreseeable ‘intervening act’ does not break the chain of causation

–

Chapman v Hearse

• Negligent medical treatment subsequent to negligent injury would not necessarily remove liability for D1 unless the subsequent injury was ‘inexcusably bad’, so obviously unnecessary or improper that it fell outside the bounds of reputable medical practice

– (Mahony v J Kruschich Demolitions)

THE LAW OF TORTS

PARTICULAR DUTY AREAS

(a) Products Liability

(b) Defective Structures

(c) Nervous Shock

PRODUCT LIABILITY

• Common law:

- Donohue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562

- Grant v Australian Knitting Mills [1936]

AC 85

PRODUCT LIABILITY

• Relevant Statutes:

Sale of Goods Act 1923 (NSW)

Pt 4 Performance of the Contract (ss.30 to 40)

Pt 5 Rights of the Unpaid Seller Against the Goods

(ss.41 to 50)

Pt 6 Actions for Breach of the Contract (ss.51 to 56)

PRODUCT LIABILITY

• Relevant Statutes:

- Fair Trading Act (NSW)

Pt 4 Consumer Protection (ss.38 to 40)

Pt 5 Fair Trading (ss.41 to 60, including s.42

Misleading or deceptive conduct and s.44 False representations)

PRODUCT LIABILITY

• Relevant Statutes:

- Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)

Pt V Div 1 Consumer Protection (ss.51AF to

65A, including s.52 Misleading and deceptive conduct)

Pt V Div 2A Actions against manufacturers and importers of goods (ss.74A to 74L)

Pt VA Liability of manufacturers and importers for defective goods

DEFECTIVE STRUCTURES

• Professional negligence:

s.5O Civil Liability Act 2002 “Peer professional opinion” (ie. The UK

“Bolam” test)

S.5P Civil Liability Act 2002 “Duty to warn” remains

• Builders:

Bryan v Maloney (1995) ATR 81- 320

• Architects:

Voli v Inglewood Shire Council (1963) 110 CLR 74

DEFECTIVE STRUCTURES

• Councils & Statutory Authorities:

- Pt 5 Civil Liability Act 2002 s.42 determining duty of care and breach of duty in relation to functions, allocation of resources, range of activities and reliance on general procedures/applicable standards; s.43 act or omission not a breach unless unreasonable; s.44; s.45 Restoration of the nonfeasance protection for highway authorities

- Common law:

Heyman v Sutherland Shire Council (1985) 157 CLR 424

Shaddock v Parramatta CC [No.1] (1981) 150 CLR 424

Parramatta CC v Lutz (1988) 12 NSWLR 293

Brodie v Singleton Shire Council Council; Ghantous v Hawkesbury City

Council (2001) 206 CLR 512

NERVOUS SHOCK

• What is nervous shock

– An identifiable mental injury recognised in medical terms as a genuine psychiatric illness.

– The sudden sensory perception that , by seeing hearing or touching – of a person, thing or event, which is so distressing that the perception of the phenomenon affronts or insults the plaintiff’s mind and causes a recognizable psychiatric illness

– It is a question of fact whether it is reasonably foreseeable that the sudden perception of that phenomenon might induce psychiatric.

• Pt 3 Civil Liability Act 2002 “Mental harm” (ss.27 to

33), especially:

–

S.30 Limitation on recovery for pure mental harm arising from shock ie.

Witness at the scene the victim being killed, injured or put in peril, or the plaintiff is a close family member of the victim

– S.32 Duty of care ie. Defendant ought to have foreseen that a person of normal fortitude might… suffer a recognisable psychiatric illness if reasonable care were not taken.

Nervous Shock:The The Nature of the Harm

• The notion of psychiatric illness induced by shock is a compound, not a simple, idea. Its elements are, on the one hand, psychiatric illness and, on the other, shock which causes it. Liability in negligence for nervous shock depends upon the reasonable foreseeability of both elements and of the causal relationship between them

• Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

• Pathological grief disorder

THE VICTIMS

• Primary victims

– What needs to be reasonably foreseeable ? Some personal injury, physical or psychiatric, to the primary victim

• Page v Smith [1996] 1 AC 155 (HL) a victim of a road accident caused by another's negligence claimed damages solely for psychiatric illness

• Secondary Victims

– Close relationship

• Jaensch v Coffey

• S.30 Civil Liability Act “Close member of the family” and “spouse or partner” defined

– proximity/nearness to accident or aftermath

•

Bourhill v Young

• Mount Isa Mines v Pusey