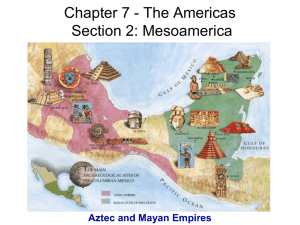

Olmec Civilization & Mesoamerican Cultures Presentation

advertisement

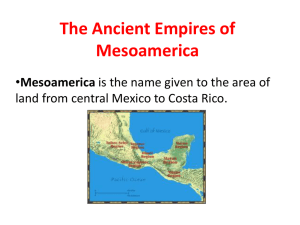

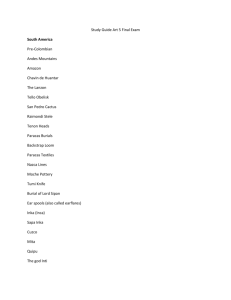

Olmec: the first Mesoamerican civilization, 1500–400 BCE. Map showing sites and sites of influence and (right) Colossal Head, one of 10 Olmec head, four San Lorenzo in Veracruz, Mexico, over 9ft high, Early Pre-classic. C. 1500-1200 BCE. Olmec head: (left) excavation, Veracruz, ca 1942; (below) at Anthropological Museum, Xalapa. The largest of the colossal heads is over 9’ high and weighs more than 25 tons, made of basalt, a stone that was brought from the Tuxtla mountains. (upper right) National Geographic artist rendering of transportation of colossal head. (left) Olmec ”Wrestler,” basalt figure of a bearded man, Early or Middle Preclassic, Veracruz, 26” H National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City (right) Olmec, Las Limas Monument, greenstone, “priest” holding infant were-jaguar deity from Las Limas, Veracruz, Middle Preclassic period, 21.5” high. Knees and shoulders incised with iconographs - profile heads of four Olmec gods with cleft heads. Considered Olmec Rosetta Stone All assertions of meaning are scholarly speculation Olmec carved jade and serpentine figures and celts (ceremonial hand axes) and figures, La Venta, Middle Formative Period. Figurines are c. 8”H; celts are 9” to 10” H. Cranial deformation, loincloths, half-open mouths with deformed teeth Olmec, hollow figures, white slipped ceramic, all 11-16” H, Early Formative (100-800 BC) Later Mesoamerican cultures induced crossed eyes in infants – sign of beauty and elegance Maya, one of 4 flints excavated at Copan representing the diety K'awiil, the spirit of the king’s scepter. Zapotec, Monte Alban, Building J, Late Preclassic (c.150BC – 150AD) Hieroglyph representing a conquered town, Building J Zapotec façade, Mitla, Oaxaca, Late Post Classic period Moche, Portraits of “Cut Lip” (L-R) at about 10 yrs, early 20s, and middle 30s ceramic, c. 300 CE Teotihuacán ["the place where one becomes a god“] looking down the Avenue of the Dead from the Pyramid of the Moon; map of Teotihuacán heartland and area of influence Taíno, Zemi, (left: back view), Dominican Republic, after 1515 CE, wood, cotton, shell, and glass, 32” H, National Ethnographic Museum, Rome. Combines Taino, European, and African materials, a syncretic spiritual object made for a high ranking cacique Aztec Empire in 1519; (right) Aztec Eagle Warrior, hollow, life-sized ceramic recovered from the Great Temple excavations. According to legend, Azteca (Mexica) tribe entered central Mexico from “Aztlan” in AD 1111. See Coe pp.186- 187 Aztec, Tenochtitlán: (left) artist’s historical rendering, (right) map made by Cortez’ from memory, published in 1524. There were three major causeways that ran from the mainland into the city which was divided into four districts and populated by more than two hundred thousand people. In 1521, Cortez demolished the ceremonial center during the course of the longest continuous battle ever recorded in military history. “The city is spread out in circles of jade, Radiating flashes of light like quetzal plumes, Beside it the lords are borne in boats: Over them extends a flowery mist.” Nahuatl poem Aztec, Templo Mayor (Great Temple); (right) excavation site in 1978 the heart of the sacred precinct in their capital city, Tenochtitlán (now in Mexico City). Only the base remains of what was once a massive double pyramid, which represented the hill where Huitzilopochtli, the god of god of war and of the sun, of the Aztec origin myth, was born Aztec, colossal stone relief of Coyolxauhqui (moon goddess) from Great Temple of Tenochtitlan, Late Post-Classic, c 11ft w; Coatlicue (Serpent Skirt), an earth goddess who gave birth to the Aztec tribal deity, Huitzilopochtli, stone, 8 ft. h Aztec, page from the Codex Borgia, duality represented by Death God back-to-back with Quetzalcoatl, Life God, surrounded by their calendar figures; (right) Aztec Calendar Stone from the Great Temple, Late Post-Classical period