PowerPoint - University of Warwick

advertisement

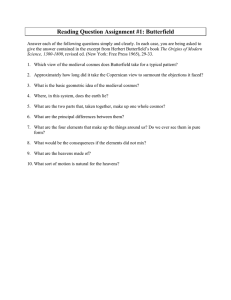

Being Human: Lecture 3 Famous Stories We Tell Ourselves (part II): The ‘Scientific Revolution’ Def. Scientific Revolution: An term that describes a period in Western history in which the way people thought about and investigated nature changed significantly. The publication of Nicolaus Copernicus's De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Sphere, 1543s) is often cited as marking the beginning of the Scientific Revolution, and its completion is attributed to the "grand synthesis" of Isaac Newton's 1687 Principia published in 1687. The Whig Interpretation of History ( 1931) The Origins of Modern Science, 1300-1800 (1948) Herbert Butterfield, 1900-1979 Dome of Science ‘Since that revolution, overturned the authority in science not only of the middle ages but of the ancient world – since it ended not only in the eclipse of scholastic philosophy but in the destruction of Aristotelian physics – it outshines everything since the rise of Christianity and reduces the Renaissance and the Reformation to the rank of mere episodes, mere internal replacements, within the system of Christendom. Since it changed the character of men’s habitual mental operation even in the conduct of the non-material sciences, while transforming the whole diagram of the physical universe and the very texture of human life itself, it looms so large as the real origin of the modern world and of modern mentality that our customary periodization of European history has become an anachronism and an encumbrance. There can hardly be a field in which it is of greater moment to us to see at somewhat closer range the precise operations that underlay a particularly historical transition, a particular chapter of intellectual development.’ (Henry Butterfield, The Origins of Modern Science, p. 7-8) ‘The very strength of our conviction that ours was a Graeco-Roman civilization – the very way in which we allowed the art-historians and the philologists to make us think that this thing which we called ‘the modern world’ was the product of the Renaissance – the inelasticity of our historical concepts, the fact – helped to conceal the radical nature of the changes that had taken place and the colossal possibilities that lay in the seeds sown in the seventeenth century.’ (p. 201) Some of his writings: On the heavens On sleep and sleeplessness On animals On the soul Virtues and vices Meteorology Metaphysics On Longlivity and Shortness of Life Poetics Generation and Corruption And many, many more … Aristotle, 384 BC – 322 BC Def. Natural philosophy: A category also known as ‘physics’. It refers to systematic knowledge of all aspects of the physical world, including living things, and in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries routinely understood as being God’s creation. It therefore possesses strong theological implications. Aristotelian cosmos Micro-Macrocosm – Man as the mirror of the wider cosmos What do natural philosophers do? • Collecting and cataloguing the wonders of God’s creation – all the things we have forgotten due to the fall • To explain why things were the way they were; they were not about ‘discovery’ But about the question. Why did God make things the way they are? The method is ‘deductive’ – from what we know to why it is the way it is Scholasticism; scholastic: Scholasticism is a term applied to the intellectual and academic style of the medieval universities, a style stressing debate, disputation, and the effective use of cannonical texts (such as those of Aristotle) in the making of arguments. A ‘scholastic’ is a practitioner of that style of thinking. Syllogism: the central technical device in formal logic in the universities of the Middle Ages and early modern period, derived from Aristotle’s writings on logic, and consisting of a ‘major premises’ (all As are B), a ‘minor premise’ (C is A), And a ‘conclusion’ (therefore C is B) Example: All men are mortal Socrates is a man Therefore Socrates is mortal ‘Science’ or ‘scientia’ in scholastic understanding: A true science demonstrated its conclusion from premises that were accepted as certain or true (in the sense of universally true for all times). Conlusions would be certain as long as they were deduced correctly from starting points that were themselves certain or true (in the sense of Universally true for all times). (see Dear, p. 5) ‘Experience’ in scholasticism : Experience for scholastics amounted to knowledge that be gained by someone who had perceived ‘the same thing’ countless times, so as to become thoroughly familiar with it. (e.g the rising of the sun) When an Aristotelian philosopher claimed to base his knowledge on experience, he meant that he was familiar with the behaviours and properties of the things he discussed. Ideally his audience would be too.( (Dear, p. 5)