document

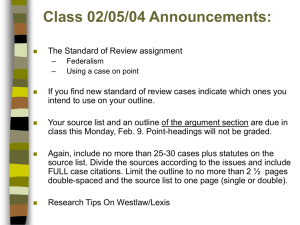

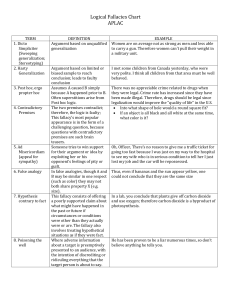

advertisement

Writing the Argument Section of the Appellate Brief What’s Up with I.R.A.C.? Four Ways Premises May Be Connected To The Conclusion Empirical Generalization Analogy Accumulation of Factors The Deductive Entailment Empirical Generalization Suppose that you have seen 1000 students who have graduated from a particular high school, and every single one has been blind. You infer that the school is a school for the blind. When you make this inference, you are making an inductive argument. What is the limitation of an inductive argument? Empirical Generalization The limitation of the empirical generalization is that the premises of your argument could be true but the conclusion false. In other words, it could be true that all the students you saw were blind but the high school was not a school for the blind. Arguing by Analogy Arguing by analogy is a common way lawyers make legal arguments. This kind of argument identifies certain similarities between the primary subject and the analogue (two things compared). Arguing by analogy is what you do when you compare the facts of your case with precedent cases. Arguing by Analogy What is the limitation of an argument by analogy? The limitation of the analogy is that someone else may be able to identify relevant differences (i.e. distinguish the precedent). Accumulation of Factors Suppose you are considering a decision about suitable office space. You think about factors such as centrality of location, cost, decor and so on. To argue that it is suitable, you point out which of the relevant features it has. Arguments of this type are called conductive. Accumulation of Factors What is the limitation of a conductive argument? Someone else might use different factors to argue the space is not suitable. The Deductive Entailment The deductive argument is the most complete relationship of logical support. A deductive argument is valid because its conclusion follows directly from its premises. The only way a deductive argument can fail is if the premises are untrue. The most simple example of a deductive argument is the syllogism. A syllogism is a statement of logical relationships. You may remember them from a philosophy class or from the L.S.A.T. Classic Example 1. All men are mortal. 2. Socrates is a man. 3. Therefore, Socrates is mortal. Power of Syllogisms Use of Deductive Reasoning. Conclusion is compelling, based on the premises. The opponent must attack the premise, not the conclusion. Parts of a Syllogism Major premise: Broad statement of general applicability. Minor premise: Narrower statement of particular applicability. Conclusion: Logical consequence of the major and minor premises. Legal Arguments as Syllogisms Major premise = statement of law. Minor premise = application of law to specific facts. Conclusion = derives from premises. Example 1. To be enforceable, a contract must be supported by consideration. 2. The contract between Tim and Mary is not supported by consideration. 3. Therefore, the contract between Tim and Mary is not enforceable. So What Are You Really Doing? I.R.A.C. Setting forth the law, and then applying it to the facts – just what you have been doing all along. Issue: Whether the contract between Tim and Mary is enforceable? Rule To be enforceable, a contract must be supported by consideration. Application The contract between Tim and Mary is not supported by consideration Conclusion Therefore, the contract between Tim and Mary is not enforceable. Relationship to Analogies Analogies help with legal reasoning. Syllogisms help with legal argument. Analogies can support a premise, but do not provide the answer (the “so what”?). To Draft a Syllogism, 1) Start with the Conclusion Determine your client’s position in the lawsuit. What does your client HAVE to argue to WIN? Write down the position. The position becomes your conclusion in the syllogism. 2) Draft the Premises The premises must be true. Specifying any two terms will determine the third. Example 1. A federal court has diversity jurisdiction over claims that exceed $75,000. 2. 3. Therefore, a federal court has diversity jurisdiction over the plaintiff’s claim. Another Example 1. 2. The plaintiff’s claim exceeds $75,000. 3. Therefore, a federal court has diversity jurisdiction over the plaintiff’s claim. 3) “Ground” the Premises You must “ground” each premise. Grounding = providing enough support for the premises to convince your audience that the premises are true. How do you ground the Major Premise? By citing to legal authorities Demonstrate that mandatory authority dictates a certain result; ground the major premise in law. Cite either a . . . – Higher court. – Statute. – Constitution. How do you ground the Minor Premise? Because a minor premise of a legal syllogism applies a legal principle to the facts of the case, the minor premise always includes some sort of factual assertion. Ground factual propositions in evidence (THE RECORD ON APPEAL). Examples of Grounding: 1. Traffic lights should be installed at dangerous intersections. Smith v. Jones (Rule) 2. The intersection at Streets A and B is dangerous. (R. at 4.) (Application) 3. Therefore, a traffic light should be installed at the intersection of Streets A and B. (Conclusion) Grounding a Legal Argument Your goal is try to create the appearance of certainty in the law, to make the judge feel like she has no choice but to find for your client. Try develop more than one way to ground the premise. You may, for example, be able to also ground your minor premise by using another syllogism. Example of Grounding the Minor Premise 1. Traffic lights should be installed at dangerous intersections. 2. The intersection at Streets A and B is dangerous. 3. Therefore, a traffic light should be installed at the intersection of Streets A and B. 1. 2. 3. Therefore, the intersection at Streets A and B is dangerous. Draft/Ground a Major Premise 1. Traffic lights should be installed at dangerous intersections. 2. The intersection at Streets A and B is dangerous. 3. Therefore, a traffic light should be installed at the intersection of Streets A and B. 1. Intersections with more than 4 accidents per year are dangerous. Allen v. Moore . 2. 3. Therefore, the intersection at Streets A and B is dangerous. Draft/Ground a Minor Premise 1. Traffic lights should be installed at dangerous intersections. 2. The intersection at Streets A and B is dangerous. 3. Therefore, a traffic light should be installed at the intersection of Streets A and B. 1. Intersections with more than 4 accidents per year are dangerous. Cite. 2. Last year there were 5 accidents at the intersection of Streets A and B. (R. at 9). 3. Therefore, the intersection at Streets A and B is dangerous. Constructing Syllogisms Gulf Sturgeon Example (handout) The Issue is whether the ESA prohibits the Pier. What is best conclusion for your client? That the ESA prohibits the pier Convert this to a Syllogism 1. 2. 3. Therefore, the ESA prohibits the pier. (Conclusion) Construct the Major Premise What Does the ESA Prohibit? 1. 2. 3. Therefore, the ESA prohibits the pier. (Conclusion) Construct the Major Premise What Does the ESA Prohibit? 1. The ESA prohibits “takings.” (Rule) 2. 3. Therefore, the ESA prohibits the pier. (Conclusion) Construct the Minor Premise 1. The ESA prohibits “takings.” 2 3. Therefore, the ESA prohibits the pier. Construct the Minor Premise 1. The ESA prohibits “takings.” 2. The pier would be a “taking.” 3. Therefore, the ESA prohibits the pier. Ground the Major Premise 1. The ESA prohibits “takings.” 2. The pier would be a “taking.” 3. Therefore, the ESA prohibits the pier. Ground the Major Premise 1. The ESA prohibits “takings”: 16 U.S.C. § 1538(a)(1). 2. The pier would be a “taking.” 3. Therefore, the ESA prohibits the pier. Ground the Minor Premise by Converting to a New Syllogism 1. The ESA prohibits “takings”: 16 U.S.C. § 1538(a)(1). 2. The pier would be a “taking.” 3. Therefore, the ESA prohibits the pier. 1. 2. 3. Therefore, the pier would be a “taking.” Construct and Ground a Major Premise for the of New Syllogism. 1. 2. 3. Therefore, the pier would be a “taking.” Construct and Ground a Major Premise for the of New Syllogism. 1. “Taking” means “harm” to an endangered species: 16 U.S.C. § 1532(19). 2. 3. Therefore, the pier would be a “taking.” Construct the Minor Premise of Your New Syllogism 1. “Taking” means “harm” to an endangered species: 16 U.S.C. § 1532(19). 2. 3. Therefore, the pier would be a “taking.” Construct the Minor Premise of Your New Syllogism 1. “Taking” means “harm” to an endangered species: 16 U.S.C. § 1532(19). 2. The pier would “harm” the Gulf Sturgeon, an endangered species. 3. Therefore, the pier would be a “taking.” Ground the Minor Premise by Converting to a New Syllogism 1. “Taking” means “harm” to an endangered species: 16 U.S.C. § 1532(19). 2. The pier would “harm” the Gulf Sturgeon, an endangered species. 3. Therefore, the pier would be a “taking.” 1. 2. 3. The pier would “harm” the Gulf Sturgeon, an endangered species. Construct and Ground a Major Premise 1. 2 3. The pier would “harm” the Sturgeon, an endangered species. Construct and Ground a Major Premise 1. “Harm” means habitat modification effecting breeding. 50 C.F.R. § 17.3 2 3. The pier would “harm” the Sturgeon, an endangered species. Construct and Ground a Minor Premise 1. “Harm” means habitat modification effecting breeding. 50 C.F.R. § 17.3 2. 3. The pier would “harm” the Sturgeon, an endangered species. Construct and Ground a Minor Premise 1. “Harm” means habitat modification effecting breeding. 50 C.F.R. § 17.3 2.The pier will modify the habitat enough to effect breeding. 3. The pier will “harm” the Sturgeon, an endangered species. Remembering IRAC: Writing the Appellate Brief I is for Identifying the Issue – This is an introduction which briefs the reader on the precise issue which you are about to discuss. – Typically, in the Appellate Brief, you will do this with your issues presented and again with your point headings and/or sub-point headings (the form of which we will discuss later). Example: Sample Memo – II. The denial of Sample’s Motion for Summary Judgment should be affirmed since, even though there is no dispute of material fact, Sample is not entitled to judgment as a matter of law. R stands for Rule Identification. (The first part of a deductive argument) You should next inform the reader of the pertinent law to the client’s situation. This rule section may include rule sentences, case discussions or both. R stands for Rule Identification. (The first part of a deductive argument) Use rule sentences to spell out for your reader an outline or the relationships between legal principles. However, where the facts of your case and the precedent cases are a relevant basis for comparison, draft a case discussion in your rule section. Using Rule Sentences Example: It is the party seeking summary judgment that bears the initial responsibility of informing the court of the basis for the motion and for demonstrating the absence of any dispute of material fact. Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 323 (1986). Case Discussions Provide Relevant Facts: In Kass v. Kass, 696 N.E.2d 174 (N.Y. 1998) the plaintiff sued for ownership of five pre-zygotes created during the parties’ marriage. (allegation) Now divorced the wife wanted them implanted, claiming it was her only chance for genetic motherhood. The husband objected to the burdens of unwanted fatherhood, claiming the wife had previously agreed that in the event of divorce, the pre-zygotes would be donated for research. (facts) The court held that the previous agreement regarding disposition was controlling. Id. at 175. (holding) Ground the Major Premise! (In this case your rule section) As, legal authorities both rule sentences and case discussion should be cited. Remember you are demonstrating that mandatory authority dictates a certain result. Cite to a higher court, statute or Constitution. If the rule is from a statute, quote the relevant part of the statute. A Stands for Application of the Rule – The heart of analysis is this application of the law to your client’s facts. – Using strong topic sentences to lead your reader through the discussion. – Demonstrate how your client’s facts meet the factual conditions of the rule which you are discussing. A Stands for Application of the Rule (Ground the minor premises) – You should also compare the facts in the record with the facts of the precedent cases; – draw links between the law and facts; – make references to important similarities/ differences with cases; – and make references to important words in a case or statute. – Finally, your application section should discuss and evaluate relevant counter-arguments to your application of the element of rule. Placement of Counter-Arguments Your counter-argument should go at the end of your analysis section (before the mini-conclusion- the conclusion on the particular issue your are discussing). UNLESS you have divided up the section into sub-issues, in which case the counter-argument should follow the respective sub-issue. For example, if you are discussing “condition or proclivity” the counterargument which addresses competency should go after that respective discussion. I. Condition or Proclivity A. Condition of Incompetence (Insert competency counter here) B. Dangerous proclivity Mini-conclusion C is for Conclusion: Your IRAC discussion should close with a statement of whether the requirements of the element have or can not be met. Mini-conclusions should follow each issue and at the end of the paper, you will have a final conclusion. The form for the overall conclusion of an appellate brief is different from the form of the memo. C is for Conclusion: Therefore, for the above-stated reasons, Appellant respectfully requests that this Court reverse the District Court’s order denying Appellant’s Motion to transfer venue, or, in the alternative, reverse the District Court’s order denying Appellant’s Motion for Summary Judgment. To be a winner, use I.R.A.C., a form of Deductive Logic in Your Brief . The End.