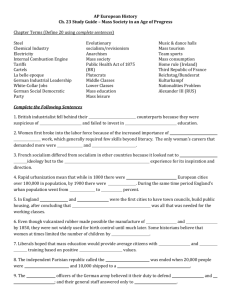

Chapter Summary

advertisement

AP European History Chapter 15 Summary CHAPTER 15 – THE BUILDING OF EUROPEAN SUPREMACY: SOCIETY AND POLITICS TO WORLD WAR I CHAPTER SUMMARY This chapter discusses the half century from 1860–1914, during which Europe’s political, social, and economic institutions took on many of their current characteristics. Nation-states with large electorates, political parties, centralized bureaucracies, and universal military service took shape. Business organized itself into large-scale corporations and labor into trade unions. White-collar workers emerged in significant numbers, and urbanism grew in importance. Socialism became a major force in political life, and the beginnings of the welfare state were seen. That trend and the establishment of vast military structures caused an increase in taxes. The period also saw the spread of industrialism, which gave Europe an unparalleled productive capacity. Through trade, the continent’s economy became intermeshed with that of the rest of the world. Europe’s population increased greatly during this period, from about 226 million in 1850 to about 401 million in 1900. A desire to enjoy the new prosperity and a spread in the use of contraception, however, led to smaller families and a decline in the population growth. Another notable population trend was migration, both in Europe from countryside to city and abroad to the Americas, Australia, or South Africa. The first trend increased European social unrest; the second relieved it somewhat. Economically, the period from 1850–1873 has been characterized as the Second Industrial Revolution, which was marked by two important trends. The European continent caught up with Great Britain, which had led the world industrially before 1850. Germany in particular emerged as a leading industrial nation. Another major change was the emergence of wholly new industries: steel, chemicals, electricity, and oil replaced textiles, steam, and iron as the most modern forms of enterprise. After 1873, Europe’s economic growth slowed down. Bad weather and foreign competition led to hard times for agriculture. After the bank failures of 1873, several industries stagnated. Europe was able to recover from depression because of improved marketing techniques, the stabilizing effects of cartels, trade associations, and government imposition of tariffs. Finally, imperialistic ventures in Africa and Asia also helped. In social terms, 1860–1914 was the age of the middle class. No longer a revolutionary group, the bourgeoisie had become the arbiter of taste and the defender of the status quo. It was no homogeneous unit, however, but one divided among a few industrial and banking magnates, larger numbers of small businessmen and professional people, shopkeepers, school teachers, and the new element of white-collar workers. There was considerable tension among these groups. After completing its overview of the nineteenth-century middle class, the chapter then focuses on late nineteenth century urban life. The authors note the rise in urban populations, the redesign of cities such as Paris, Manchester, and Vienna, and the emphasis upon urban sanitation and improvement of housing conditions among the poor —especially through philanthropy and public housing. An extended section on the varieties of women’s experience in the late century follows , emphasizing class distinctions among women, as well as the rise of political feminism. The discussion of late nineteenth-century women's experiences is followed by a section that details the emancipation of European Jews from ghetto life into a world of nearly equal citizenship The chapter then turns to a discussion of the place of the labor movement and socialism in late nineteenth-century politics. During this period, the working classes grew in numbers and in importance. Although its living standard improved constantly, the urban proletariat was still faced with impersonal work, poverty, poor housing and working conditions, and high medical costs. Workers voiced their discontent in new institutions, among them trade unions, which flourished after 1870. The adoption of the democratic franchise in most of Europe led to its first mass political parties, in which workers played key roles. Unions and political parties presented new opportunities for Europe’s socialists, who generally sought change within the existing political framework rather than through violent revolution. In the First International, founded in 1864, Karl Marx himself made considerable accommodation to the revolutionary movement. Marxism emerged as Europe’s single most important strand of socialism. The text then details the socialist movements within Great Britain, France, and Germany. In the last decade of the nineteenth century, the czars industrialized Russia. Popular discontent and socialist parties followed behind. The more radical Social Democratic Party had to function in exile due to czarist repression. After 1900, Lenin became one of its leaders. He contributed two important ideas to European socialist doctrine: the leadership of a small elite party of professional revolutionaries and an alliance of workers and peasants. The Revolution of 1905 forced the czar to establish a parliament (Duma), but he was soon able to blunt its effect. A promising agricultural reform program was mired by 1911. The regime began to consider war as a means of winning support.