TAP Chapter 17: Manifest Destiny and Westward Migration

advertisement

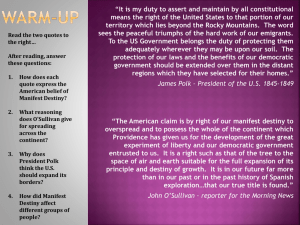

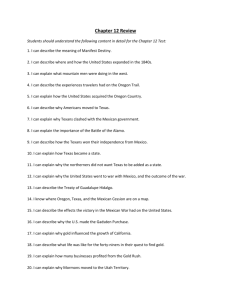

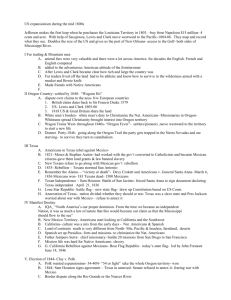

TAP Chapter 17: Manifest Destiny and Westward Migration Essential Questions: Where do we see evidence of Americans embracing “manifest destiny” during the 19th Century? Do American exceptionalism and manifest destiny live on today in American diplomacy? What does the “provocation” of the Mexican-American War reveal about the American approach to expansion? Why did the Mexican cession pose a crippling problem for America? Presidential Politics of the Expansion Era After Andrew Jackson’s second presidential term, Martin Van Buren won the election of 1836. His administration was marred by economic difficulties caused by Jackson’s financial strategies and insistence on the Specie Circular, and he battled the fallout of the Panic of 1837 early in his term. Following his difficult term, William Henry Harrison, hero of the War of 1812, a famous rugged outdoorsman, and a member of the Whig party, won the election of 1840 on the deliberately constructed campaign slogan, “Tippecanoe and Tyler, too!” that appealed to American public embracing democratic, rather than aristocratic, values. Harrison only served a month before dying in office, and his vice president, John Tyler, became president. Although Tyler was a Whig, his party grew enraged at his failure to support the party’s platform (their support of a new national bank and a protective tariff) and they called him a Democrat in Whig clothing. James K. Polk, a classic Jacksonian Democrat focused on western expansion, followed Tyler in 1844, and he was responsible for the annexation of Oregon and the Mexican-American war, which led to territory gains in the West. The election of 1848 resulted in a win for Zachary Taylor, a Mexican-American war hero, and a win for the Whigs. “Gone to Texas” Mexico had become independent from Spain in 1821, and under the leadership of Stephen Austin, thousands of Americans had immigrated to Texas. Ignoring decrees from the Mexican government, Texans refused to free their slaves following Mexico’s abolition of slavery. Following a rebellion in 1835 and the famous showdown at the Alamo, Texas proclaimed her independence from Mexico in 1836. The citizens of Texas, many of whom were American slave owners who had emigrated in search of fertile land and who had established large ranches, had long desired to become part of the United States. The issue had first presented itself during Andrew Jackson’s administration, but he tabled the issue, fearing the conflict that was sure to erupt over the issue of slavery. Between 1836 and 1844, Texas existed in limbo-land, as Mexico refused to officially recognize Texan independence. Sensing British interest in Texas, American politicians finally embraced in the issue during the campaign of 1844. Pro-expansion Democrats advocated for annexation while antislavery and anti-expansion Whigs protested, but Tyler finally succeeded in bringing Texas into the union in 1845. Oregon Just as Texas beckoned to Southerners, expansion-minded Americans equally coveted the Oregon territory. At various times, the Oregon territory had been claimed by the U.S., Spain, Russia, and England. By 1844, only America and England claimed the territory, and each nation had citizens inhabiting the land under a “joint occupation” agreement. The Oregon issue, like Texas, became prominent during the election of 1844, when expansion-minded democrats declared “All of Oregon or None.” James Polk won the presidency in 1844, on a platform that emphasized two main points: acquiring the Oregon territory from the British, and pushing west to extend slavery. He popularized slogans such as "The Whole of Oregon or None!" and "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight!" Finally, nervous that America was willing to fight a war over the land, the British acquiesced and the border was set at the 49th parallel in the Oregon Treaty of 1846. Manifest Destiny As Congress agreed to annex Texas and the Oregon territory, a journalist named John O’Sullivan wrote the following: “And that claim is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.” With this quotation, he coined the famous term that described the sentiment of the expansionist era, encapsulating the American belief that God had given America the mission to spread democracy throughout the Americas, and that such a mission was the destiny of the nation. Ten years earlier, French sociologist Alexis de Tocqueville had made a similar observation about Americans in his 1835 book, Democracy in America. He noted that Americans passionately believed in the extraordinary nature of their nation and democratic mission, a concept he called “American exceptionalism.” Do American exceptionalism and manifest destiny live on today in American diplomacy? The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) Just like Texas and Oregon, Polk and the expansionists had their eyes set on California, which was owned by Mexico. Polk also harbored concerns about America’s claims to Texas, as Mexico still viewed Texas as a Mexican territory in rebellion, and to complicate the situation, the Southern boundary of Texas was in dispute. Polk offered to purchase California, but the Mexican president refused. Polk, eager to force Mexico into engagement, sent a war message to Congress, but it wasn’t until Mexican troops crossed the disputed boundary of the Rio Grande that he was able to claim that Mexican troops had shed American blood on American soil and forced a war declaration, even though it required a bit of fabrication on his part. What does this “provocation” of war reveal about the American approach to expansion? General Zachary Taylor led the American charge to the Mexican city of Buena Vista, which was followed by General Winfield Scott’s charge toward Mexico City. As soon as Scott reached Mexico City, Polk began peace negotiations, which resulted in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. According to the treaty, America gained Texas and all of the land west to California (about half of Mexico’s land claims), in exchange for about $18 million. Despite the remarkable territorial gains of the war (called the Mexican Cession), the new land posed a challenge that would deadlock Congress for months: the question of slavery in the new and hotly coveted Western land. Indeed, the issue of slavery in the newly-acquired territory would divide the country for years. David Wilmot, a Congressman from Pennsylvania, proposed that slavery be banned in land acquired from the Mexican War. The plan, called the Wilmot Proviso, was given to Congress in August 1846. It never passed the Senate, but passed the House. It was taken out of the War Appropriations bill in order for Senate to pass the actual bill and was abandoned in favor of the Compromise of 1850. Why did the Mexican cession pose a crippling problem for America?