SF II Essay II by Ly..

advertisement

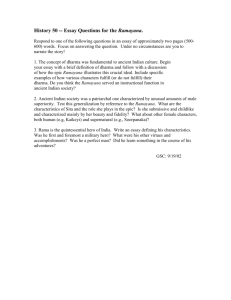

Lynn Shin 28 April 2013 Hagai Segal Social Foundations II “Sakuntala’s lack of exposure in the West is not surprising. India has seemed inaccessible, its spiritual messages foreign to many western audiences used to naturalism and secular stories. However, in this new millennium, as India and its culture are finding a stronger foothold in the West, many of its ideas, such as dharma and karma, are becoming better known and understood”. Discuss this quotation with specific references to The Recognition of Sakuntala, the Indian culture and values that it reflects, and their resonance to readers beyond India. It is with a profoundly western conceit that countries have attempted to contextualize India- a country steeped in mystery and eluding definition. The lens of examination is decidedly myopic, and consequently, by the very attempt to classify India do we cause it to slips through our fingers. There are words, general feelings that conjure up at the thought of India. Spiritual, mythical-petty phrases that attempt to blanket a vast and seamless culture. Beyond it, the country is intangible, it seems “disorganized” to our rationalist senses, due in part because we choose often to understand it on only our own terms. Religion itself is a western conception, “Conditioned by the concept of 'religion', and in search of a unified system of religious faiths and beliefs amongst the people they called 'Hindus'… the Catholic missionaries of the sixteenth century manufactured the word 'Hinduism'” [1]. It is this misconception of Hinduism that has proliferated, even in India itself, to become the common blanket term for the multifaceted system of abstract notions and faiths among Hindus. But its foundation is built on an erroneous misconception: that “religion” is a universal concept. Thus, the act of familiarizing the unfamiliar invalidates itself. So we build again, from the start. If there is a single phrase more encompassing to the Indian sense of self, it is dharma, literally meaning to uphold or support. It is a concept that refers to the order necessary to keep the universe maintained, upheld. The phrase includes and goes beyond the rule of religion itself, it is both a secular and religious concept. Here, by its very definition, dharma is a divergence from western thought that predicates a strict divide between the secular and non-secular, “Reason was not opposed to faith, man was not against nature, the individual was not set against society, nor against himself” [2]. Dharma may be secular, but it is not thought of in terms of strict polarity. Nature or man, individual or society, religious or non-religious: these either/or situations are an occidental construct. This underlines the lack of exposure of Indian culture to the west. Even the basis of its defining notions has no European equivalent; “The word dharma which the Indian 1 traditions have rendered familiar has no really adequate counterpart in the terminology of European languages” [3]. There is no real basis of comparison, no English parallel. In a less esoteric definition, dharma is the guidelines and rules laid out that detailed the appropriate behaviors for humans. It encompasses various subcategories that affect a person’s behavior: their caste, gender, age, and occupation. Thus behavior correct for one person is not necessarily correct for another. It is by performing an individual’s dharma, well or badly, in their present life that gives them good or bad karma, meaning “action” in Sanskrit. In turn, good or bad karma affects their state of reincarnation in the next life. Potentially moving up or down a caste as necessary. Thus, motivation is intrinsic and essential, what an individual does on the earth, to the earth, matters. Yet something at the core of Hinduism’s central principles rubs western minds the wrong way. The idea of doing one’s own duty to varying factors can be objectionable, even abhorrent, to an individual born on the bred and butter of his assumed preeminence, “No other intellectual tradition has been as intensively (some would say: excessively) preoccupied with singling out and defining the individual self than Western philosophy, and no other polity has made the presumed rights and prerogatives of the individual as central a concern as Western societies” [4]. Since Socrates, since the revamp of Renaissance humanism, since the consequent revamp of capitalism and imperialism of the 18th century, individualism has created a legacy for itself. It goes back to one of the most influential western texts: the Old Testament, “God spoke to Adam: "Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth" [5]. From God’s first words to Adam, it is made clear: Adam's job is to name- and thus establish dominance- over the animals and the earth. And yet individualism should not be thought exclusively in terms of superiority over something, just as India, while not in technical terms being individualistic, should be thought of as it’s polar opposite. In fact, Indian concepts like dharma and karma have gained prominence in recent years, if only in a distorted and commoditized manner that appeals to western sensibility. Especially in the coming backlash against consumerism, materialism, and global warming: side effects of man’s great individualistic legacy. If Indian texts were to sneak through the divide between two worlds, it would be in the form of texts like the Recognition of Sakuntala. The play was the first Indian drama to be translated into a English in 1789, and it reflects many cultural and religious notions- some accessable, some not. One that would ring out in an enviroment-concerned 21st century is the emphasis put on nature. In Sakuntala, nature plays almost a role of its own. It is a catalyst, saying and doing things 2 that the people cannot. The text is dotted with natural metaphors, especially the more sensual images, “ Even hidden in the duckweed, the lotus glows” [6]. India’s emphasis on modesty is analagous to the propriety of its literature. Love scenes are set off stage, and even a sultry metaphor as described is kept strictly in natural terms. Even King Dushyanta’s description of Sakuntala’s beauty likens her to a blooming flower, “Her lips are like red, red shoots of a vine, Her arms are as delicate as its winding stems” [7]. Nature is inextricably linked to the very words of the story. But its role goes beyond just words, nature takes real physical action to move the story along. Just as the King deliberates on how to reveal himself, it is the appearance of the bee that gives him an opppurtunity, “Sakuntala: I think this rascal bee would not leave off. Scat! Shoo! No, he won’t listen. I must leave the place. Oh, no! Help!” [8]. It could be immodest, or at least, unfitting to the story’s tropes, that the king step forward without a proper reason. So, nature offers him a reason. The persistent bee allows the king to step forward and assume the role of the protector, and also fits tongue-in-cheek with sexual metaphor of a bee (Dushyanta) pollinating a flower (Sakuntala). The story would have been well known to Indian audiences, and often nature feels almost brazen, pushing and prodding two love-struck fools to remember their lines, remember to continue the story. When it is appropriate for the King to leave, the signaling of an elephant crashing into the ashram provides a break between the first sight, and the pursuit. A common trope found in occidental classics like Romeo and Juliet. And when Sakuntala’s feet is pricked by the Kusa grass while leaving, it allows her to trail behind her friends and give longing looks back at the king. The implication here is an important one, and central to Indian philosophy: nature is essential. With the theory of reincarnation, trees and flowers are no longer “just” nature, but potential people whose karma has placed them there. Thus, there is an importance in treating well the things around you. There is a dharma, or duty, to treating the environment with respect, and the outcome of an individual’s karma is dependent on it. This is a concept that meshes well with current European sensibilities, though it sometimes results in an oversimplification of India’s concept of a higher goal. Yet the presentation of the title character, Sakuntala, creates problems. She seems to only be defined and weighted as “good” by her beauty. Thus by simply existing, her looks validate herself. She rarely voices a true opinion, though one must remember that Sakuntala’s behavior would be interpreted in traditional Indian audiences as appropriate. “Sakuntala's behavior from here on must be interpreted as reflecting a highly desirable quality in a young woman: modesty” [9] . While she shows little interest in the king (as in accordance with her dharma), her asides reveal her true feelings, “Sakuntala (whispering to herself): O heart, keep quiet! Anasuya is 3 asking the same questions I’ve wanted to ask” [10]. Yet by the framework of her character, Sakuntala must naturally be coy, beautiful but virtuous, hospitable: it is a women’s duty. The punishment for breaching one’s duty is a heavy one, and Sakuntala pays the price when she neglects her role, “The incident by which Durvasa's rage is aroused may seem slight, but the duty to travelers is a sacred one. Because the girl forgot to honor Durvasa, Durvasa will forget to honor her” [11]. The punishment seems extreme to audiences unfamiliar to Sakuntala. The trope of breaking one’s duty, and exacting its toll, is not necessarily foreign. In the Arabian Nights, in The Story of the Merchant and the Demon, a merchant inadvertently kills the son of a jinni, who demands retribution, “I must kill you as you killed him- blood for blood” [12]. The word must is key and the jinni, like Durvasa, cannot take back his curse and can only modify it. The strict observance to Sakuntala’s dharma as a woman can seem alienating misogynistic to western audiences. Yet to write it off completely assumes that there are no similarities. But the common dating tropes we see in real life, and are reinforced in our movies and television, mirror many of the ones we see in Sakuntala. The basic roles women and men play today- of the pursued and the pursuer- echo of what we read in the text. Sakuntala is punished for not understanding her station and pursuing the king on her own, and consequently loses her ring while dangling it in the river. She steps outside of her role as a women and is reproved. But it is not all that difficult to see, even now, a woman who actively “chases” a man, rather than letting him pursue her seems unattractive. The tropes we unconsciously emulate have veins in Sakuntala’s story. And while it is unnecessary for a girl to be entirely virtuous in western society, girls are still treated differently then men when they step outside their cosigned boundaries. Slut shaming is still prevalent. There are rules; we just choose not to say them aloud. The most unnerving realization may not be that the occidental and oriental are that different, but that we are often more similar than we think (or want to be). And Indian concepts like dharma and karma still gain in prominence, a likely reason eloquently stated by Marco Pallis, in his book A Buddhist Spectrum, “The truths to which [Indian ideas like] dharma corresponds in the field of metaphysical ideas and spiritual and even social applicability are among the ones which, by the questions they raise, are troubling people's minds most acutely at this moment” [13]. At the heart of westerners growing fascination with India is exactly the intangible “solution” that is steeped in its supposed mysticism: a growing need for order in the universe amidst material excess. Simply put, we are looking for answers. Word count: 1748 4 Works Cited: 1) Badrinat, Chaturvedi. Dharma: The Individual and World Order. India International Centre Quarterly: Vol. 17, No. 2 (Monsoon 1990), pp. 30. India International Centre. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/23002161> 2) Badrinat, Chaturvedi. Dharma: The Individual and World Order. India International Centre Quarterly: Vol. 17, No. 2 (Monsoon 1990), pp. 29. India International Centre. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/23002161> 3) Pallis, Marco. A Buddhist spectrum: Contributions to Buddhist-Christian Dialogue. pp. 125. New York: Seabury Press, 19811980. Print. 4) Jorn K. Bramann: The Educating Rita Workbook. Copyright © 2004. <http://facultyfiles.frostburg.edu/phil/forum/Descartes.html> 5) Bloom, Harold. The Bible. New York: Chelsea House, 1987. Print. 6) Kalidasa. The Recognition of Sakuntala. 1998. <http://public.wsu.edu/~brians/world_civ/worldcivreader/world_civ_reader_1/sakuntala. html> 7) Kalidasa. The Recognition of Sakuntala. 1998. <http://public.wsu.edu/~brians/world_civ/worldcivreader/world_civ_reader_1/sakuntala. html> 8) Kalidasa. The Recognition of Sakuntala. 1998. <http://public.wsu.edu/~brians/world_civ/worldcivreader/world_civ_reader_1/sakuntala. html> 9) Brians, Paul. Study Guide for Kalidasa: The Recognition of Sakuntala. 1997. < http://public.wsu.edu/~brians/love-in-the-arts/sakuntala.html> 10) Kalidasa. The Recognition of Sakuntala. 1998. <http://public.wsu.edu/~brians/world_civ/worldcivreader/world_civ_reader_1/sakuntala. html> 11) Brians, Paul. Study Guide for Kalidasa: The Recognition of Sakuntala. 1997. < http://public.wsu.edu/~brians/love-in-the-arts/sakuntala.html> 12) Haddawy, Husain, Muhsin Mahdi, and Daniel Roazen. The Arabian nights. pp. 22 New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2010. Print. 13) Pallis, Marco. A Buddhist spectrum: Contributions to Buddhist-Christian Dialogue. pp. 125. New York: Seabury Press, 19811980. Print. 5