Dynamic Social Balance

advertisement

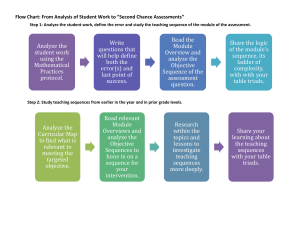

Dynamic Social Balance James Moody Ohio State University Freeman Award Presentation Sunbelt Social Network Conference, February 2005 My formal collaboration network Dynamic Social Balance Outline Dynamic Social Balance 1. Introduction 2. Adolescent Friendship Structure a. Hierarchy b. Network Change 3. Theory a. Traditional Social Balance Models b. A Local-change Balance Model 4. Observed Results 5. Simulation Results 6. An Addendum on Asymmetry… Dynamic Social Balance Introduction A Gallery of Friendship Networks 588 adolescents from a poor, urban, southern school. (Source: Add Health) Dynamic Social Balance Introduction A Gallery of Friendship Networks 1744 adolescents from a lower-middle class, urban, school in the West. (Source: Add Health) Dynamic Social Balance Introduction A Gallery of Friendship Networks 413 adolescents from a Upper-class, urban, school in the Midwest. (Source: Add Health) Dynamic Social Balance Introduction A Gallery of Friendship Networks 776 adolescents from a working-class, all-white, suburban, school in the Midwest. (Source: Add Health) Dynamic Social Balance Introduction A Gallery of Friendship Networks 678 adolescents from a working-class, all-white, rural, school in the Midwest. Across all of these settings (and many more) we can literally see the differences imposed by classic ‘Blau space’ features of youth communities. Race, grades, SES etc. often shape the gross topography of school friendship networks. (Source: Add Health) Dynamic Social Balance Introduction Distribution of Popularity Community type Size By size and city type Dynamic Social Balance Introduction While we revel in the diversity of social settings, a primary motivation for social theory is to explain common features across settings and account for social differentiation endogenously. •Cartwright, Harary, Davis, Leinhardt, Johnsen: Clustering & hierarchy in social networks •Chase: The development of dominance •Gould: Peer influence embellishments on quality stratification •Mark: Social Differentiation from first principles •McFarland: Development of ritualized structure in dynamic networks Adolescent friendship networks vary on myriad surface features, but do these networks have a common structural form and if so how can we explain it? Dynamic Social Balance Adolescent Friendship Networks: Data Data •I use the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health). This is a nationally representative survey of adolescents in school (7th through 12 grade), with (approximately) complete network data in 129 schools, including data over time for a smaller subset of schools. •Each students named up to 5 best male and 5 best female friends. •Nominations outside of the school were allowed, but not matched. •These data are available through the Carolina Population Center: Methods •Features of the global network structure are identified through triad distribution methods and block models •Specific hypotheses about social balance are tested with exponential random graph models* •Dynamic implications for these models are derived from simulation studies grounded in the observed data. *pseudo-likelihood logit approximations for ERGM Dynamic Social Balance Adolescent Friendship Networks: Triad distributions Endogenous Building Blocks: A periodic table of social elements: (0) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) 003 012 102 111D 201 210 300 021D 111U 120D 021U 030T 120U 021C 030C 120C Dynamic Social Balance Adolescent Friendship Networks: Triad distributions The distribution of triads found in any network determines its final structure. For example, if all triads are 030T, then the network must be a perfect linear hierarchy. Triads Observed: 030T Dynamic Social Balance Adolescent Friendship Networks: Triad distributions Triads Observed: 102 300 N* M M Dynamic Social Balance Adolescent Friendship Networks: Triad distributions Triads Observed: 102 300 003 N* M M N* N* N* N* M M “Cluster” Dynamic Social Balance Adolescent Friendship Networks: Triad distributions Triads Observed: 003 012 021D 021U 030T 120D 120U 300 M A* A* A* A* N* Eugene Johnsen (1985, 1986) specifies a number of structures that result from various triad configurations: M M A* A* A* A* N* M M “Ranked Cluster” Dynamic Social Balance Adolescent Friendship Networks: Triad distributions The observed distribution of triads can be fit to the hypothesized structures using weighting vectors for each type of triad, and formulas for the conditional expectation of the triad counts. (l ) (lT lμ T ) l T l Where: l = 16 element weighting vector for the triad types T = the observed triad census mT= the expected value of T T = the variance-covariance matrix for T Dynamic Social Balance Adolescent Friendship Networks: Triad distributions For the 129 Add Health school networks, the observed distribution of the tau statistic for various models is: Suggesting that the “ranked-cluster” models beat random chance in all schools. Dynamic Social Balance Adolescent Friendship Networks: Block Models Regular equivalence can be identified by disaggregating triad distributions into the positions that nodes occupy within triads (Hummell and Sodeur 1990; Burt 1990). This creates a set of triad position profiles that you can then cluster over to identify equivalent classes 003 021C_S 030T_S 120U_E 012_S 021C_B 030T_B 120U_S 012_E 021C_E 030T_E 120C_S 012_I 111D_S 030C 120C_B 102_D 111D_B 201_S 102_I 111D_E 201_B 210_S 021D_S 111U_S 120D_S 210_B 021D_E 111U_B 120D_E 021U_S 111U_E 021U_E 120C_E 210_E 300 Dynamic Social Balance Adolescent Friendship Networks: Block Models If we use block models instead, over all 129 networks, we find a similar clear hierarchy in each school, differing only in the number of levels that might form a ‘semi-periphery’ position in the network. Over half of the networks had one of these 6 image networks Dynamic Social Balance Adolescent Friendship Networks: Relational stability While the structure appears constant, relations are fluid: Percent of T2 relations that were also T1 relations Time 2 T1 T2 Time 3 Dynamic Social Balance Adolescent Friendship Networks: Position stability An individual’s position in the status hierarchy is also not stable: Jefferson Sunshine Dynamic Social Balance Adolescent Friendship Networks These results suggest that: • All of the school networks have a rank-strata structure • The structure remains constant even though nearly half of all relationships are new •People’s position in the popularity distribution is fluid What social process will explain a stable macro-structure in the face of dynamic relations? Dynamic Social Balance Traditional models for directed graphs Classic balance theory offers a set of simple local rules for relational change: •A friend of a friend is a friend •My enemy’s enemy is my friend. Extended to directed relations, balance is typically operationalized as transitivity: If: i j & j k then: i k Actors seek out transitive relations and avoid intransitive relations Dynamic Social Balance Traditional models for directed graphs Classic balance theory offers a set of simple local rules for relational change: •A friend of a friend is a friend •My enemy’s enemy is my friend. (0) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) 003 012 102 111D 201 210 300 021D 111U 120D Intransitive Transitive 021U 030T 120U 021C 030C 120C Mixed Dynamic Social Balance Traditional models for directed graphs Support for the classic balance model is strong, based on an over-representation of transitive triads in observed networks: •Davis (1970) finds support in 742 different networks, which was further specified by Johnsen (1985) •Hallinan’s work on schoolchildren (1974) •Numerous studies of the Newcomb Data (Dorien et al 1996, for example) •…and the extent of order holds even net of clustering imposed through focal activity (Feld, 1980). But two troubling points remain: •Equilibrium models suggest networks should crystallize into stable structures. •Observed networks always contain intransitive patterns (i.e. t210) much more frequently than expected by chance. •My goal is to specify a systematic balance model that can account for both of these points. Dynamic Social Balance New models for directed graphs Two crucial insights help inform a modified approach to social balance: •Triples instead of triads. Operationalizing balance theory as transitivity allows us to simplify the behavioral assumptions (cf. Hummel and Soduer (1987, 1990. •Structural implications differ depending on your position in the network. •Carley and Krackhardt (1996) show this clearly at the dyad level, and we would expect similar effects at the triple level. •Examine relational change directly. Instead of assuming that intransitive relations resolve in equilibrium, we need to ask the microimplications of moving from one structural state to another. •This allows us distinguish transitivity seeking from intransitivity avoidance. Dynamic Social Balance New models for directed graphs 102 030C 120C 111U 021C 201 003 012 111D 021D 300 210 120U vacuous transition Increases # transitive Decreases # intransitive 030T Decreases # transitive Increases # intransitive 021U 120D Vacuous triad Intransitive triad Transitive triad (some transitions will both increase transitivity & decrease intransitivity – the effects are independent – they are colored here for net balance) Dynamic Social Balance New models for directed graphs: Triad Transitions Observed triad transition patterns, from Sorensen and Hallinan (1976) 030C 120C 102 111U 201 021C 111D 003 012 210 021D 021U 120U 030T 120D 300 Dynamic Social Balance Triad-Transition models on observed data The triad transition model can be tested on observed graphs within the ERGM (p*) framework by specifying the triad-transition counts weighted by the number of transitive and intransitive triples that would be created in each transition. Here I use the pseudo-likelihood approximations based on a dyadic logit model (Wasserman and Pattison, et al). The model includes additional parameters for dyadic properties, individual expansiveness and attractiveness, out-of-school ties, and reciprocity. I estimate this model on the Add Health networks, creating a distribution of parameter scores across all networks. Dynamic Social Balance Triad-Transition models on observed data ERGM Coefficient Distributions* 0.8 Endogenous Focal Orgs. Dyadic Similarity/Distance. 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 *Coefficients based on pseudo-likelihood approximations, here standardized so they fit well on the page… Dynamic Social Balance Triad-Transition Simulations Based on these results, I simulate networks dynamically: •Tie probabilities are based on separate parameters for seeking transitivity and avoiding intransitivity, using the triad change counts. •Adds a parameter to limit the marginal returns to forming new relations, effectively dampening (but not hard-coding) outdegree. •Reciprocity & dyad similarity parameters are held constant across all simulations. •As iterations pass, actors adjust their ties based on the resulting model probabilities, allowing the graph to evolve in response to others’ changes. Dynamic Social Balance Triad-Transition Simulations Final Graph Transitivity R2 = 0.82 Dynamic Social Balance Triad-Transition Simulations Structural Stability Correlation of network structure at tfinal with t-5% R2 = 0.54 Dynamic Social Balance Triad-Transition Simulations Total Graph Transitivity At moderate transitivity/intransitivity A single simulation run, showing the wide swings in graph transitivity. Similar trends evident in reciprocity, though the number of arcs and general shape (variance/skew) of the popularity distribution does not fluctuate much. Dynamic Social Balance A dyadic extension: Gould’s asymmetry avoidance rule Under moderate parameter values, these simulations meet the empirical requirements: • Systematic balance-based action can create a dynamic equilibrium. • Graphs evaluated at any of the later points in the simulation have high rank-cluster tau values. • We observe more t210 triads than we would expect by chance. The key features of this model are: • balance is treated as a parameter that scales from weak to strong. • the focus for actor behavior is the emotional return to relational change, not the total elimination of particular triads. • transitivity seeking has different implications than intransitivity avoidance. • But the simulations are somewhat sensitive to parameter changes. • Some runs suggest that once the network passes a particular structural threshold, a ‘lock-in’ process takes hold and graphs do not change much. Dynamic Social Balance A dyadic extension: Gould’s asymmetry avoidance rule •What effect of asymmetry? Consider these triads: 030T 120D 120U The current model rewards reciprocation, but does not penalize asymmetry, so these triads are stable for 2 of the 3 actors. Gould suggests that people will not maintain a relation if it is not reciprocated, and that’s also exactly what we see in the Add Health data. Adding a parameter that says actors avoid long-term asymmetry will make these three triads temporarily attractive, but unstable in the long run. (run network balance simulation now) Dynamic Social Balance Conclusion •Specific: •A social balance model that takes seriously the process of avoiding intransitive settings or seeking transitive ones fits the patterns found in Add Health •Transitivity seeking creates more stability than intransitivity avoidance •Endogenous balance is only a part of the model: •Dyadic attributes and focal organization set the constraints in real graphs. •The most robust dynamic models are those that include a dyad level cost for repeated asymmetry. Dynamic Social Balance Conclusion •General: •There are many other local dynamic processes models to specify. For example: • Actors seeking to maximize structural holes are effectively seeking the t201 triad, but how do they get there? Do different routes to t201 imply different actor motivations? •Actors move on multiple relations simultaneously, implying a network with compound edges, and thus a more complicated (but finite and specifiable) triad census. •Micro structures of more than 3 nodes (4-cycles, etc). •If we can specify the things that actors do with respect to their relations, we can build these models in any context.