Genocide in Rwanda - White Plains Public Schools

advertisement

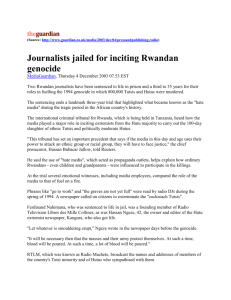

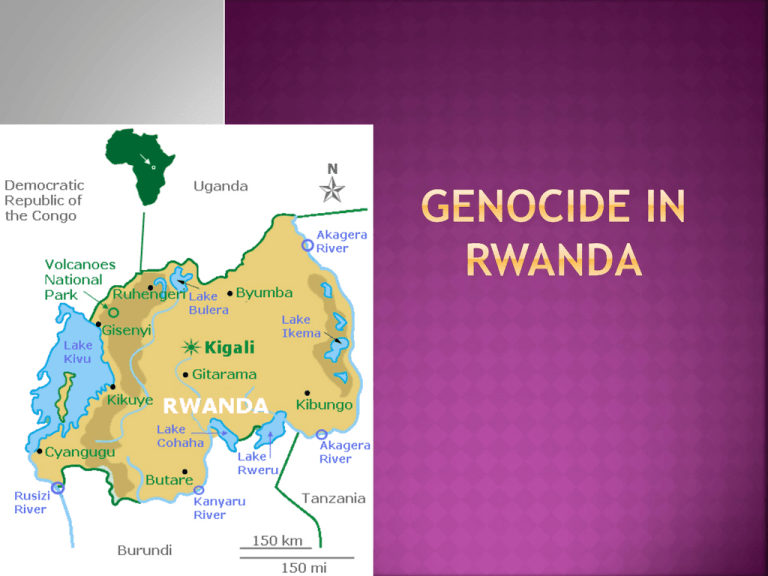

The Sources: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/1288230.stm http://www.historyplace.com/worldhistory/genocide /rwanda.htm http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/1252049.stm ~Most of the dead were Tutsis ~And most of those who perpetrated the violence were Hutus ~Even for a country with such a turbulent history as Rwanda, the scale and speed of the slaughter left its people reeling Beginning on April 6, 1994, and for the next hundred days, up to 800,000 Tutsis were killed by Hutu militia using clubs and machetes with as many as 10,000 killed each day The genocide was sparked by the death of the Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu, when his plane was shot down above Kigali airport on April 6, 1994 Rwanda is one of the smallest countries in Central Africa, with just 7 million people, and is comprised of two main ethnic groups, the Hutu and the Tutsi Although the Hutus account for 90 percent of the population, in the past, the Tutsi minority was considered the aristocracy of Rwanda and dominated Hutu peasants for decades, especially while Rwanda was under Belgian colonial rule There had been disagreements between the majority Hutus and minority Tutsis, but the animosity between the ethnic groups grew substantially since the colonial period Ironically, the two ethnic groups are actually very similar - they speak the same language, inhabit the same areas and follow the same traditions However, Tutsis are often taller and thinner than Hutus, with some saying their origins lie in Ethiopia During the genocide, the bodies of Tutsis were thrown into rivers, with their killers saying they were being sent back to Ethiopia When the Belgian colonists arrived in 1916, they produced identity cards classifying people according to their ethnicity The Belgians considered the Tutsis to be superior to the Hutus Not surprisingly, the Tutsis welcomed this idea, and for the next 20 years they enjoyed better jobs and educational opportunities Resentment among the Hutus gradually built up, culminating in a series of riots in 1959 More than 20,000 Tutsis were killed, and many more fled to the neighbouring countries of Burundi, Tanzania and Uganda Over subsequent decades, the Tutsis were portrayed as scapegoats for every crisis At the same time, Tutsi refugees in Uganda – supported by some moderate Hutus – were forming the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) Their aim was to overthrow Habyarimana and secure their right to return to their homeland Habyarimana chose to exploit this threat as a way to bring back dissident Hutus back to his side, and Tutsis inside Rwanda were accused of being RPF collaborators In August 1993, after several attacks and months of negotiation, a peace accord was signed between Habyarimana and the RPF, but it did little to stop the continued unrest When Habyarimana’s plane was shot down at the beginning of April 1994, it was the final nail in the coffin Exactly who killed the president – and with him the president of Burundi and many chief members of staff – has not been established The effect of the killing was both instantaneous and catastrophic In Kigali, the presidential guard immediately initiated a campaign of retribution Leaders of the political opposition were murdered, and almost immediately, the slaughter of Tutsis and moderate Hutus began Since all individuals in Rwanda carried identification cards specifying their ethnic background, a practice left over from colonial days These ‘tribal cards’ now meant the difference between life and death Amid the onslaught, the small U.N. peacekeeping force was overwhelmed as terrified Tutsi families and moderate politicians sought protection Among the peacekeepers were ten soldiers from Belgium who were captured by the Hutus, tortured and murdered As a result, the United States, France, Belgium, and Italy all began evacuating their own personnel from Rwanda However, no effort was made to evacuate Tutsi civilians or Hutu moderates Instead, they were left behind entirely at the mercy of the avenging Hutu Back at U.N. headquarters in New York, the killings were initially categorized as a breakdown in the cease-fire between Tutsi and Hutu Throughout the massacre, both the U.N. and the U.S. carefully refrained from labeling the killings as genocide, which would have necessitated some kind of emergency intervention On April 21, the Red Cross estimated hundreds of thousands of Tutsi had already been massacred since April 6 – an extraordinary rate of killing Encouraged by the presidential guard and radio propaganda, an unofficial militia group called the Interahamwe (meaning those who attack together) was mobilized At its peak, this group 30,000 strong Soldiers and police officers encouraged ordinary citizens to take part In some cases, Hutu civilians were forced to murder their Tutsi neighbors by military personnel Participants were often given incentives, such as money or food, and some were even told they could appropriate the land of the Tutsis they killed On the ground at least, the Rwandans were largely left alone by the international community UN troops withdrew after the murder of 10 soldiers The day after Habyarimana’s death, the RPF renewed their assault on government forces, and numerous attempts by the UN to negotiate a ceasefire came to nothing The U.N. Security Council responded to the worsening crisis by voting unanimously to abandon Rwanda The remainder of U.N. peacekeeping troops were pulled out, leaving behind a only tiny force of about 200 soldiers for the entire country The Hutu, now without opposition from the world community, engaged in genocidal mania, clubbing and hacking to death defenseless Tutsi families with machetes everywhere they were found The Rwandan state radio, controlled by Hutu extremists, further encouraged the killings by broadcasting non-stop hate propaganda and even pinpointed the locations of Tutsis in hiding The killers were aided by members of the Hutu professional class including journalists, doctors and educators, along with unemployed Hutu youths and peasants who killed Tutsis just to steal their property Many Tutsis took refuge in churches and mission compounds These places became the scenes of some of the worst massacres In once case, at Musha, 1,2000 Tutsis who had sought refuge were killed beginning at 8 a.m. and lasting until the evening Hospitals also became prime targets as wounded survivors were sought out and then killed In some local villages, militiamen forced Hutus to kill their Tutsis neighbors or face a death sentence for themselves and their entire families They also forced Tutsis to kill members of their own families By mid May, an estimated 500,000 Tutsis had been slaughtered Bodies were now commonly seen floating down the Kagera River into Lake Victoria Finally, in July, the RPF captured Kigali The government collapsed and the RPF declared a ceasefire As soon as it became apparent that the RPF was victorious, an estimated two million Hutus fled to Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) These refugees included many who have since been implicated in the massacres Rwanda’s now Tutsi-led government has twice invaded its twice much larger neighbor, saying it wants to wipe out the Hutu forces And a Congolese Tutsi rebel group remains active, refusing to lay down arms, saying otherwise its community would be at risk of genocide The world’s largest peacekeeping force has been unable to end the fighting Primary Source: Hamis Kamuhanda, 11 years old in 1994 “The following day we had rumors that Hutus were out to kill every Tutsi in the country, claiming that we, the Tutsis had killed the Hutu president. We were advised to stay indoors. I had never seen my parents so agitated and terrified all my life.” “Then there was a knock at the door and before we could even respond, the door fell in and about four or so people came in and dragged my father out by his legs. That was the last we saw of him.” “We were hiding under the bed but we could see everything. Mother told us to keep quiet. Then the shooting began. The bullets came in and hit everything in the way. Yet no one dared to scream. Mother could not cover all of us. I could feel blood coming from under my right shoulder and I did not know whether I was hit or not. I could not feel any pain then. My mind was occupied with the terror being hacked to death.” “Suddenly the door burst open and they came in praising themselves for a good job done. I was closer to the door and they kicked me in my belly. It was painful but the thought of being severed alive with their machetes, made me stay as quiet as a mouse.” “One of them said: ‘Let’s make sure that he is dead with this.’ I didn’t move an inch, nor did I make any noise. They must have thought that I was dead. I just felt a very sharp pain on my leg and I must have passed out…When I woke up, mother was nursing my wounded leg…” “…The armed Hutu men, the Interahamwe, were scattered and patrolling every corner. The situation was tense for a very long time and we could smell the stench of the dead even inside our fenced house. We were terrified.” “We thought that those men were going to return and realize that we, a Tutsi family were still breathing. The leg was getting worse and I was feverish all the time.” “The fact that at age 11, my mother had to do everything for me, including helping me to relieve myself, drove me insane. We were running out of food. We kept praying for some rescue mission from somewhere.” “Mother peeped through the wall and saw Tutsi soldiers coming towards the house. She prayed and waited for our fate. What would it be? It was RPF (Rwanda Patriotic Front) soldiers. These were good people.” “They liberated us and freed us from our selfimposed solitary confinement. The RPF soldiers took me to the hospital. I was there for about six months.”