File

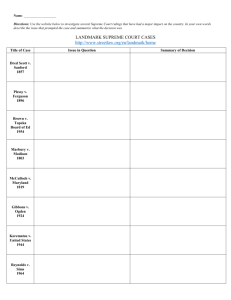

advertisement

The Long Road to Equality: 14th Amendment Equal Protection Landmark Cases From 1880 to 2011 A Wikipedia primer compiled On September 18, 2011 100 U.S. 303 (1880), was a United States Supreme Court case about racial discrimination. At the time, West Virginia excluded AfricanAmericans from juries. Strauder was an Black man who, at trial, had been convicted of murder by an all-white jury. Strauder appealed his conviction, contending that West Virginia exclusionary policy violated the Equal Protection Clauseof the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886), was the first case where the United States Supreme Court ruled that a law that is race-neutral on its face, but is administered in a prejudicial manner, is an infringement of the Equal Protection Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In 1880, the city of San Francisco passed an ordinance that persons could not operate a laundry in a wooden building without a permit from the Board of Supervisors. Although most of the city's wooden building laundry owners applied for a permit, none were granted to any Chinese owner. Yick Wo (益和, Americanization: Lee Yick), who had lived in California and had operated a laundry in the same wooden building for many years and held a valid license to operate his laundry issued by the Board of Fire-Wardens, continued to operate his laundry and was fined $10.00 for violating the ordinance. He sued for a writ of habeas corpus after he was imprisoned in default for having refused to pay the fine. Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision in the jurisprudence of the United States, upholding the constitutionality of state laws requiring racial segregation in private businesses (particularly railroads), under the doctrine of "separate but equal". "Separate but equal" remained standard doctrine in U.S. law until its repudiation in the 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) was a unanimous United States Supreme Court decision addressing civil government institutedracial segregation in residential areas. The Court held that a Louisville, Kentucky, city ordinance prohibiting the sale of real property toAfrican Americans violated the Fourteenth Amendment, which protected freedom of contract. Unlike prior state court rulings that had overturned racial zoning ordinances on takings clause grounds due to those ordinances' failures to grandfather land owned prior to enactment, the Court in Buchanan ruled that the motive for the Louisville ordinance, race, was an insufficient purpose to make the prohibition constitutional. Skinner v. State of Oklahoma, ex. rel. Williamson, 316 U.S. 535 (1942), was the United States Supreme Court ruling which held that compulsory sterilization could not be imposed as a punishment for a crime, on the grounds that the relevant Oklahoma law excluded white-collar crimes from carrying sterilization penalties. Under Oklahoma's Habitual Criminal Sterilization Act of 1935, the state could impose a sentence of compulsory sterilization as part of their judgment against individuals who had been convicted three or more times of crimes "amounting to felonies involving moral turpitude". The defendant, Jack T. Skinner, had been convicted once for chicken-stealing and twice for armed robbery. Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case upholding the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066, which ordered Japanese Americans into internment camps during World War II. The 6-3 decision, written by Supreme Court justice Hugo Black, held that the need to protect against espionage outweighed Fred Korematsu's individual rights, and the rights of Americans of Japanese descent. During the case, Solicitor General Charles Fahy suppressed a report from the Office of Naval Intelligence indicating that "there was no evidence Japanese Americans were disloyal, were acting as spies or were signaling enemy submarines." Korematsu's conviction for evading internment was overturned on November 10, 1983. The US District Court for the Northern District of California voided Korematsu's original conviction because in Korematsu's original case, the government had knowingly submitted false information to the Supreme Court that had a material effect on the Supreme Court's decision. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948), is a United States Supreme Court case which held that courts could not enforce racial covenants on real estate. The Court considered two questions. First, are racially-based restrictive covenants legal under the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution? Secondly, can they be enforced by a court of law? The United States Supreme Court held that racially-based restrictive covenants are, on their face, valid under the Fourteenth Amendment. Private parties may voluntarily abide by the terms of a restrictive covenant but may not seek judicial enforcement of such a covenant because enforcement by the courts would constitute State action. Since such state action would necessarily be discriminatory, the enforcement of a racially-based restrictive covenant in a state court would violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The court noted that the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed individual rights, and equal protection of the law is not achieved with the imposition of inequalities. Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case that decided that Mexican Americans and all other racial groups in the United States had equal protection under the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Pete Hernandez, a Mexican agricultural worker, was convicted for the murder of Joe Espinosa. Hernandez's legal team set out to demonstrate that the jury could not be impartial unless members of non-Caucasian races were allowed on the juryselecting committees; no Mexican American had been on a jury for more than 25 years in the Texas county in which the case was tried. Hernandez and his lawyers appealed to the Texas Supreme court, and appealed again to the United States Supreme Court. Chief Justice Earl Warren and the rest of the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of Hernandez, and required he be retried with a jury composed without regard to ethnicity. The Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment protects those beyond the racial classes of white or negro, and extends to other racial groups, such as Mexican American in this case. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional. The decision overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 which allowed statesponsored segregation. Handed down on May 17, 1954, the Warren Court's unanimous (9–0) decision stated that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." As a result, de jure racial segregation was ruled a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution. This ruling paved the way for integration and the civil rights movement. Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a landmark civil rights case in which the United States Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, declared Virginia's anti-miscegenation statute, the "Racial Integrity Act of 1924", unconstitutional, thereby overturning Pace v. Alabama (1883) and ending all race-based legal restrictions on marriage in the United States. The court ruled that Virginia's anti-miscegenation statute violated both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. “Marriage is one of the "basic civil rights of man," fundamental to our very existence and survival.... To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State's citizens of liberty without due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discrimination. Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State.” The Supreme Court concluded that anti-miscegenation laws were racist and had been enacted to perpetuate white supremacy: “There is patently no legitimate overriding purpose independent of invidious racial discrimination which justifies this classification. The fact that Virginia prohibits only interracial marriages involving white persons demonstrates that the racial classifications must stand on their own justification, as measures designed to maintain White Supremacy.” Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971), was an Equal Protection case in the United States in which the Supreme Court ruled that the administrators of estates cannot be named in a way that discriminates between sexes. After the death of their adopted son, Sally and Cecil Reed sought to be named the administrator of their son's estate; the Reeds were separated. The Idaho Probate Court specified that "males must be preferred to females" in appointing administrators of estates, so Cecil was appointed administrator. In a unanimous decision, the Court held that the law's dissimilar treatment of men and women was unconstitutional. From Chief Justice Burger's opinion: To give a mandatory preference to members of either sex over members of the other, merely to accomplish the elimination of hearings on the merits, is to make the very kind of arbitrary legislative choice forbidden by the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment; and whatever may be said as to the positive values of avoiding intrafamily controversy, the choice in this context may not lawfully be mandated solely on the basis of gender. Examining Board v. Flores de Otero, 426 U.S. 572 (1976), was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States that invalidated a state law that excluded aliens from the practice of civil engineering. The Court invalidated the law on the basis of equal protection using a strict scrutiny standard of review. Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan, 458 U.S. 718 (1982) was a case decided 5-4 by the Supreme Court of the United States. The court held that the single-sex admissions policy of the Mississippi University for Women violated the Equal Protection Clause of theFourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996), is a landmark United States Supreme Court case dealing with civil rights and state laws. It was the first Supreme Court case to deal with LGBT rights since Bowers v. Hardwick (1986), when the Court had ruled that a law criminalizing homosexual sex was constitutional. An amendment to the Colorado state constitution ("Amendment 2") that would have prevented any city, town or county in the state from taking any legislative, executive, or judicial action to recognize gay and lesbian citizens as a protected class was passed by Colorado voters in a referendum. A state trial court issued a permanent injunction against the amendment, and upon appeal, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that the amendment was subject to "strict scrutiny" under the Equal Protection Clause. The state trial court, upon remand, concluded that the amendment could not pass strict scrutiny, which the Colorado Supreme Court agreed with upon review. Upon appeal to the United States Supreme Court, the Court ruled in a 6-3 decision that the amendment did not even pass the rational basis test, let alone strict scrutiny. The decision in Romer set the stage for Lawrence v. Texas (2003), where the Court overruled its decision in Bowers. Rejecting the state's argument that Amendment 2 merely blocked gay people from receiving "special rights", Kennedy wrote: To the contrary, the amendment imposes a special disability upon those persons alone. Homosexuals are forbidden the safeguards that others enjoy or may seek without constraint. Perry v. Schwarzenegger (also known as Perry v. Brown on appeal) is a federal lawsuit filed in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California challenging the federal constitutionality of Proposition 8, a 2008 ballot initiative that amended the California Constitution to provide that "only marriage between a man and a woman is valid or recognized in California." In effect, it prohibited the recognition of same-sex marriages performed on or after November 5, 2008. The suit sought to strike down Proposition 8 as unconstitutional. On August 4, 2010, Chief Judge Vaughn Walker ruled that Proposition 8 violated the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. On August 16, 2010, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ordered the judgmentstayed pending appeal.[2] The case is widely regarded as a landmark case that will likely reach the Supreme Court on appeal.[3][4][5] The plaintiffs' attorneys, Theodore Olson and David Boies, were listed on the 2010 Time 100 for their nonpartisan and strong legal approach to challenging Proposition 8.[6] On August 4, 2010, Walker announced his ruling in favor of the plaintiffs, overturning Proposition 8 based on the Due Process andEqual Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[77] Walker concluded that California had no rational basis or vested interest in denying gays and lesbians marriage licenses:[78] An initiative measure adopted by the voters deserves great respect. The considered views and opinions of even the most highly qualified scholars and experts seldom outweigh the determinations of the voters. When challenged, however, the voters’ determinations must find at least some support in evidence. This is especially so when those determinations enact into law classifications of persons. Conjecture, speculation and fears are not enough. Still less will the moral disapprobation of a group or class of citizens suffice, no matter how large the majority that shares that view. The evidence demonstrated beyond serious reckoning that Proposition 8 finds support only in such disapproval. As such, Proposition 8 is beyond the constitutional reach of the voters or their representatives. He further noted that Proposition 8 was based on traditional notions of opposite-sex marriage and on moral disapproval of homosexuality, neither of which is a legal basis for discrimination. He noted that gays and lesbians are exactly the type of minority that strict scrutiny was designed to protect.