WORD - Rural Institute - University of Montana

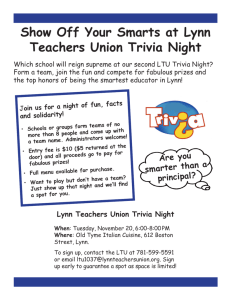

advertisement