CORONERS ACT, 1975 AS AMENDED

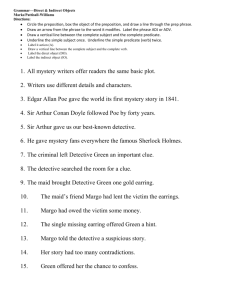

advertisement