THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF THE SELF

advertisement

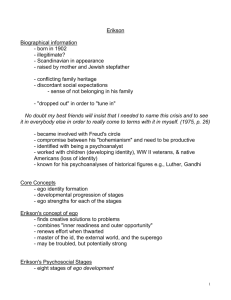

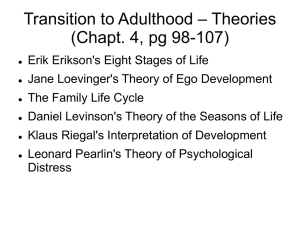

THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF THE SELF VELIMIR B. POPOVIĆ, PH.D. JUNGIAN PSYCHOANALYST EGO AND SELF: TERMINOLOGY W. James (1910) “I” vs. “me” “I” – the self as knower and doer “me”, or myself as known or experienced Concerning the “myself”, as known, W. James included: • a material self which contained one’s body, one’s family and one’s possessions; • a social self which was a reflection of the way other people see the individual; and • a spiritual self, which included emotions and desires. • James recognized that all these aspects of the self were capable of evoking feelings of heightened or lowered self-esteem. • Finally, James described the self as carrying a feeling of basic unity and continuity. C. H. Cooley (1912) • “self” as that which is designated in common speech by the pronouns of the first person singular – I, me, mine, myself. • The self is characterized by stronger emotion than is the non-self. • Cooley introduced the concept of the “looking-glass self” – the individual perceiving himself in the way others see him/her. G. H. Mead (1934) • Mead argued that the self-concept in fact arises out of the individual’s concern about how others react to him. • Mead also hypothesized a “generalized other” to account for generalized feelings about oneself. G. W. Allport (1955) - Proprium • “Proprium”: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Awareness of a bodily self. Sense of a continuity over time. A need for self-esteem. An extension of the “I” or ego beyond the borders of the body. An ability to synthesize inner needs and outer reality. A self-image, a perception and evaluation of the self as an object of knowledge. There is the self as knower and doer. There is on occasions a need to increase tensions, expand awareness, seek and meet challenges etc. Ego and self in psychoanalysis S. Freud • 1896: “das Ich” (the Ego); Freud regarded the ego as as the organ of defence, and, at the same time, he knew that some defences are unconscious; • 1914-1915 he distinguished between: a. ego instincts ( here ego means oneself) and b. object instincts. the Ego vs. the Super-ego • “primary narcissism” – state of the infant as that of boundaryless self-love where self and not-self ware as yet undifferentiated; • child’s ego develops out of this state by displacement of libido on to the mother and later on to an ideal. S. Freud (1923): ”The ego and the id” • The ego is a coherent organization of mental processes. • Consciousness is attached to ego (it controls the approaches to motility and goes to sleep at night, and even than it censors the dreams). • It is responsible for repressions and resistances. • Part of the ego is unconscious, and “behaves exactly like the repressed” in producing powerful effects. • Freud derives neuroses from a conflict between the coherent ego and the repressed which is split from it (and contained in the Id). • The ego is in fact part of the Id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world through the medium of perceptions. • The ego mediates between the instincts (the Id) and the external world through the reality principle and not through self-regard. • Freud describes the ego in its relations to the Id as like a man on horseback; often, he says, the man has to guide the horse where he wants to go. • The ego is first and foremost a body ego, ultimately derived from bodily sensations, and itself the projection of the bodily surface. M. Klein, D. Winnicott & E. H. Erikson • M. Klein uses the concept “ego” to mean both: – the subjective “I” or “myself”, and – the “system ego”, with its various stageappropriate ways of enhancing, depending and strengthening itself. • Thus, the ego arises out of some mental representations of itself E. H. Erikson (1950) • The ego is an “inner instrument”, evolved to safeguard order within the individual. • For Erikson, the ego is kind of person dwelling between the extremes of the “bestial” impersonal id and the conscience which is often harsh and restrictive. • The ego keeps tuned to reality and integrates the individual planning and orientation. • Finally, for Erikson, the ego is clearly a self with human feelings, closely related to wellbeing and good self-esteem; • He extends the concept of the “I” to that of a personal identity and describes “ego growth” and its failures. • Personal identity has primarily mediating function between inner and outer needs, between instincts and standards, etc. D. W. Winnicott (1965) For Winnicott, the ego represents an integrating function of the brain present from the beginning (thus, an anencephalic child would have an id and no ego, whereas an baby with a normal brain would already have an ego as well as an id). • So, for Winnicott the ego is there from the start. • In fact, the ego is the starting point from which a self-representations develops. • Thus, the ego is a function of personality which permits a unified development of subjectivity. • The self arrives only after the child has begun to use the intellect to look at what others see or feel or hear, and what they conceive of when they meet this infant body. • Ego development depends on ego-supportive mother. • Differentiation into “I” and “you”, into “I” and “non-I”, the development of subjective objects and of objectively experienced objects, and of capacity for realism proceeds gradually so long as the mother understands the child’s reality limitations. • Thus, for Winnicott the ego is original integrating function, while the self is oneself as distinct from other people, and its emergence is importantly dependent on how others experience an individual; in other words, self is a function of reflection from others. H. HARTMANN, H. KOHUT & O. KERNBERG • H. Hartmann (1950) was the spearhead of the psychoanalytic theorizing about the ego/self. • Hartmann was the first to make a clear distinction between “ego” and “self”. • For Hartmann, the ego is not defined in terms of self-feeling, the experience of “I”, or any other subjective experience or subjectively experienced datum, but as a system of adaptive and integrative functions hierarchically arranged. So, functions of defense and antinstictual aspects are included in the functions of the ego. • In similar way as Winnicott, Hartmann defines the self as experiental: it has to do with feelings and subjective experience and with the distinction between myself and not-me. • For example, he says that: “it will therefore be clarifying if we define narcissism as the libidinal cathexis not of ego but of the self” (1964). • He distinguished three phenomena: a) the ego, a structure or a hypothetical mental suborganization encompassing the mind’s executive and instrumental functions and the defense mechanisms; b) the self-representation, which is the person’s (conscious and unconscious) mental conception or image of him/herself; c) the self proper – the actual objective person, his/her body, his/her identity as seen or known by an external observer (therefore for him the self was not truly a psychological concept at all). H. KOHUT (1971, 1977) • Hartmann’s bifurcation of “ego’ from “self” helped H. Kohut in his clinical work on narcissism and narcissistic disorders as well in his theoretical considerations. • The “self” is not just a set of subjective images, ideas, and the like but a psychological structure of central importance to the personality. • The self in Kohut’s terminology has to do with the representation of the self in the psyche, analogous to the representations of other persons and things in the psyche (“objectrepresentations”). • The self develops through “transmuting internalizations” of what he identified as normal early infantile phases: the grandiose self and idealized “selfobject”. • In the first of these stages, the infant feels omnipotent, grand and omniscient, and in the second he/she attributes power and grandeur to the main parental figure (“selfobject”). • In Kohut’s self psychology the term ‘selfobject’ is used to refer to the subjective or intrapsychic experience of another person (strictly speaking not the person herself) who is felt to be necessary for the maintenance of the cohesion, vitality or integrity of the self. A selfobject is anyone who keeps us feeling glued together and enhances our sense of wellbeing (Kohut, 1971; 1977; 1984). • So to speak, baby experiences important figures (“selfobejcts”), unconsciously, not as fully separate, independent individuals, but as extension of, or part of, the self. Hence, the term “selfobject” designates the lack of full self-other separation and the infant’s fundamental structural dependency on such primitively conceived “others”. • In infancy, the selfobject must provide the baby with certain particular forms of responsiveness in order for the early phases to develop fully and then be internalized, forming self-structure. • On the other hand, the absence of these responses prevents adequate structure from being formed, and as a consequence of this deficiency, the self’s “cohesion and firmness depend on the presence of a selfobject and … it responds to the loss of the selfobject with simple enfeeblement, various regressions, and fragmentation” (1977). • Such subjects have not achieved the type of mature, integrated self-image and selfstructure – “nuclear self” – which is necessary before people can be related to as truly separate “objects”. • So, the child’s selfobjects must respond adequately for these needs - to be loved, protected and mirrored - in order to help the infant to integrate them into the structures of his/hers personal self. • Kohut believed that the need for selfobject relationships begins in infancy and remains throughout life. This need matures but never leaves us. • Kohut’s work leads to a very different value system than the autonomy-independence emphasis of classical psychoanalysis. Selfobject theory is consistent with the notion of the underlying unity of all consciousness. We are linked to each other by means of our relationships, which act as a kind of ‘glue’ binding us together. • We are always selves embedded in a matrix of selfobjects who are responsive to our needs to varying degrees, in ways that sustain us or bind us together. We are never selves in a psychological vacuum. • Intrapsychically the self does not end at the skin. It includes those who are affectively important to us. Selfobject experiences are subjective; intrapsychically and often unconsciously the other is acting as a part of the self, carrying out functions that the self cannot provide for itself and in this way acting as a psychological extension of the self. Thus, selfobject needs are like cement for the developing personality. • In infancy, qualities of the child’s self, such as its structural integrity and vitality, are determined by the qualities of his selfobject relationships, since they are used as the building blocks of the child’s own sense of self. To the extent that the selfobject milieu is helpful, the self develops with cohesion and resilience; to the extent that the milieu is unresponsive to the child’s unfolding selfobject needs, the self develops varying degrees of structural deficit and proneness to fragmentation. When the child’s selfobject needs are unmet, they remain active but immature; there is then a lifelong need to find someone to supply them. The mirror-hungry or idealization-hungry personality lacks the internal glue which would make him or her feel put together, and so constantly searches for cohesion externally by means of a relationship or situation which will provide what is missing. Major selfobject needs: 1 Mirror needs. These include such needs as those for affirmation and confirmation of our value, for emotional attunement and resonance, to be the gleam in somebody’s eye, to be approved of, seen, wanted, appreciated and accepted. Here the developmental necessity is to transform healthy infantile grandiosity and exhibitionism into mature adult self-esteem, normal levels of ambition, pride in performance and an inner sense of one’s own worth. 2 Idealization needs. These include the need for an alliance with, or to be psychologically a part of, a figure who carries high status and importance, who is respected, admired, wise, protective and strong. This figure can be a source of soothing when this is needed; he or she is both calming and inspiring. The intrapsychic experience of merger with the idealized selfobject lends us the strength to maintain ourselves when we are afraid or gives us direction when we are in search of meaning and goals. The developmental thrust here is both towards the capacity to be selfsoothing and also to have an inner sense of direction based on one’s own ideals and goals. 3 Twinship, kinship or alter ego needs. These involve the need for sameness with others, and the sense of being understood by someone ‘like me’. To be in a community of people of shared beliefs and attitudes in which one belongs, or to have the sustaining presence of even one such person, is supporting and enhancing to the self. 4 The selfobject of creativity. During periods of taxing creative activity there may be a need for transient merger with another person. 5 The adversarial selfobject (Wolf, 1988). There is sometimes a need for a benign adversary acting as an opposing force who allows active opposition. This confirms one’s autonomy at the same time as that person continues to be supportive and responsive. 6 Efficacy needs allow us to feel that we can have an effect on the other person and that we are able to evoke what we need from him. ‘If I can elicit a response I must be somebody.’ • All of this emphasis on our ineradicable connection to others moves psychotherapy out of what Stolorow and Atwood (1992) call ‘the myth of the isolated mind’. O. Kernberg (1982) • For Kernberg, the self is one aspect or manifestation of the functioning of the entire personality – an organizing array of images, memories, experiences, ideas, and other psychic “representations” that pertain to the person as subject – or self. • Kernberg reserves the term self for “the sum total of self-representations in intimate connection with the sum total of object representations” (1982). • He was of opinion that the infant normally has many different self-representations, only some which reflect positive feelings, while others involve anger, fear, and other dysphoric affects. • From this perspective, each person may be said to have not one but many “selves”, which reflect the varied and often conflicting forces in the mind. • Sometimes, Kernberg speaks of a self as “an ego function and structure that evolves gradually from the integration of its component self-representations into a supraordinate structure” (1982). • On other occasions he was of opinion that the self as the term is meaningful only when defined in terms of self-representations. The self in Gestalt therapy “Self” refers to the system of contact making and withdrawal at any given time. Self is a person’s experience associated with figure forming in the figure/background process by which contacts between the person and the environment are regulated. Self is the power that forms a Gestalt from the personenvironment field. It is not in the person; rather it is experience of the person of the person-environment matrix, depending upon the environmental background as well as the animal-organismic background of the person for the elements that are composed into the figure during the contact-making and withdrawal process. … Self is the creative adjusting carried forward by the person acting as agent, … self is the person in action. (P. Lichtenberg, 1987). Personality: is a specific and relatively stable way of organizing the cognitive, emotive and behavioral components of one’s experience. The meaning (cognitive) that one attributes to events (behavioral) and the feelings (emotive) that accompany such events remain relatively stable over time and give an individual a sense of identity (G. Delisle). E. POLSTER • From Polster’s perspective human being does not have one self but “ a population of selves”; • all those selves are real, i.e., if one self is obscured from person’s attention it does not mean that it is more/less real than the manifested self; • all these selves need to be coordinated with each other; • each self has identity of its own. • According to Polster, “selves are formed by a configurational reflex, which takes the disparate details of personal experience and forms them into a unified patter.” • Person is constituted of different selves. • Person is more comprehensive term than self. • Person is, so to speak, a monistic concept, while the self (selves) is pluralistic one. • Contrary to the person, the self could be outside the awareness. Terminology of the self in jung, neumann & fordham The Jungian Self: A Subject superordinate to the Ego • As early as the 1920’s, Jung realized that within human personality there is not one, but two subjects. For him, the ego was conscious subject, yet he formulated the idea of a second, more primary psychological structure which includes the conscious and unconscious dimensions of the psyche. This superordinate other subject, Jung called the Self. The ego in its relation to the Self behaves as “moved” to a “mover”, or as “an object” to “the subject”. So to speak, in Jung’s theory the ego loses its primacy to the Self. • The self is seen as the agency within/without the psyche, superordinate to the ego, moving the personality towards maturity and completion. Representing the totality of the psyche, it functions as a self-regulating agency, an internal self-care system. Or, to put id differently, the Self is the agency in the personality responsible for psychic cohesion, the creation of personal values, self-esteem, and individuation. C. G. Jung used the word self to describe (at various times): 1. a primary unity inseparable from cosmic order; 2. the totality of the individual, 3. a feeling or intimation of such totality, an experience of “wholeness”; 4. an unknowable totality of consciousness, and as such it is the field where all experience occur; 5. a primary organizing force or agency outside the conscious “I”; 6. the predisposition to organize a center of consciousness; 7. subjective experiences of a personal self. • For Jung, the concept self represents totality (of the: a. conscious and the unconscious; b. soma and psyche), and is used mainly as an “not-me” force, the center of the psyche that is usually not experienced clearly by the conscious “I”. • Sometimes, he depicts the self as an entity beyond the psyche (subject). • In Jung’s theory “self”, as total personality, includes “ego” in itself. So, “ego” which mainly consists of functions of adaptation and defense, is a center of awareness or consciousness. • He does not distinguish in his use of the term ego between the subjective “I”, “me”, “myself”, or “mine” and the functions of defense and adaptation. • “The ego (is) complex factor to which all conscious contents are related … It forms, …, the centre of the field of consciousness and, … , the ego is the subject of all personal acts of consciousness. The relation of a psychic content to the ego forms the criterion of its consciousness, for no content can be conscious unless it is represented to a subject”. (Jung, CW 9 II, § 1) • Occasionally, Jung regards the ego as “a sort of complex”. Complexes are mostly unconscious, behaving like “splinter” or subpersonalities or subselves affecting consciousness, behavior, emotions and cognitive abilities but avoiding direct relationship with the “I”. • Jung’s “ego” is an integrating and organizing force (like all other complexes) and both organizing function and the subjective unity of the “I” may become fragmented (as in schizophrenia). • The “I” is erratic and loose, and it could attach itself to the various subpersonalities of the individual, which results in a migration of “Ifeeling” between the different subselves/splinter personalities (for example “I” could migrate into the dream-ego) . • Sometimes, Jung defines ego as “a complex datum of experience”, which is constituted first by a general awareness of one’s body and existence, and secondly by memory data. In this way, his “ego” is similar to Winnicott’s, Hartmann’s and Kohut’s “self”. • Jung’s “ego” is object of one’s self-esteem, self-awareness and self-value. • His “ego” is also the active, willing, doing “I” (agency). Transcendent Self vs. personal self • Personal self is equivalent to the development of a capacity to understand the meaning of “I” and is concerned with the experience of subjectivity as a coherent and continuous sense of being a particular person (W. Colman, 2000). • Personal self (or Ego, according to Jung) is the self of which we are conscious and, as such, forms a content of consciousness as well as being its centre. • Transcendent Self is always that which goes beyond consciousness, that which is greater than what I take to be “my self”. • Personal/immanent self is derivative of the transcendent Self. That is, through the processes of the unfolding and the de-integration some contents of the Self are “incarnated” in temporal life of the ego; therefore this leads to the Self being experienced as a content of the ego. The ego becomes aware of the fact that its existence partakes of something greater; this awareness requires a capacity for recognizing symbolic reality. • In this sense, the existence of the Self depends upon ego-consciousness: the Self is felt as “within” even though it is also felt as greater than the ego. That is, the Self, as in psychoanalysis, is seen as a content of the ego. • Yet, the Self is, also, as the archetypal content, experienced as a content “outside” the ego. The Self is felt outside the ego in two ways: 1. As a center about which the ego revolves or orients, a core wisdom and energy far greater than that of the ego; 2. As transcendent in the sense of beyond psyche, not only outside the ego but also beyond being in any way felt as within, whether as a content of the ego or as a center around which the ego exists. THE NUMINOSITY OF THE SELF In a letter written in August, 1945, Jung states that: [T]he main interest of my work is not concerned with the treatment of neurosis but rather with the approach to the numinous. But the fact is that the approach to the numinous is the real therapy and inasmuch as you attain to the numinous experiences you are released from the curse of pathology. (Jung, 1973, 377) Jung borrowed the word ‘numinous’ from Rudolf Otto’s (1958) book The Idea of the Holy, which had a major influence on Jung’s thought (CW 11, 222 and 472). According to Otto, the essence of holiness, or religious experience, is a specific quality which remains inexpressible and ‘eludes apprehension in terms of concepts’ (Otto, 1958, 5). To convey its uniqueness he coined the term ‘numinous’ from the Latin numen, meaning a god, cognate with the verb nuere, to nod or beckon, indicating divine approval. Otto (being a Kantian) felt that the numinous is sui generis, non-rational, irreducible—a primary datum, which cannot be defined, only evoked and experienced (1958, 7). For him, the presence of the numinous is the crucial element of religious experience; it is felt to be objective and outside the self (1958, 11). The numinous grips or stirs the soul with a particular affective state, which Otto describes as a feeling of the ‘mysterium tremendum’. Here is his description: The feeling of it may at times come sweeping like a gentle tide, pervading the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship. It may pass over into a more set and lasting attitude of the soul, continuing, as it were, thrillingly vibrant and resonant, until at last it dies away and the soul resumes its ‘profane’, non-religious mood of everyday experience. It may burst in sudden eruption up from the depths of the soul with spasms and convulsions, or lead to the strangest excitements, to intoxicated frenzy, to transport, and to ecstasy. It has its wild and demonic forms and can sink to an almost grisly horror and shuddering. It has its crude, barbaric antecedents and early manifestations, and again it may be developed into something beautiful and pure and glorious. It may become the hushed, trembling and speechless humility of the creature in the presence of— whom or what? In the presence of that which is a mystery inexpressible and above all creatures. (Otto, 1958, 12) Jung’s ideas of the Self cannot be grasped without reference to its numinous nature: Religion, as the Latin word denotes is a careful and scrupulous observation of what R. Otto aptly called the numinosum, that is, a dynamic agency or effect not caused by an arbitrary act of will. On the contrary, it seizes and controls the human subject, who is always rather its victim than its creator. The numinosum – whatever its cause may be – is an experience of the subject independent of his will. Every creed is originally based on the one hand upon the experience of the numinosum and on the other hand upon pistis, that is to say, trust or loyalty, faith and confidence in a certain experience of a numinous nature and in the change of consciousness that ensues. The conversion of Paul is a striking example of this. We might say, then, that the term “religion” designates the attitude peculiar to a consciousness which has been changed by experience of the numinosum. (Jung, CW 11, § 6) • The numinous strikes a person with awe, wonder and joy, but may also evoke fear, terror and total disorientation. Being confronted with the power of the self arouses such emotions, which always and everywhere have been associated with religious experience. FEARS OF THE NUMINOSITY OF THE SELF 1. A fear of being flooded by archetypal energies of the Self and of being overtaken by a will greater than that of one’s ego. Experience of the Self is always, as Jung said, a defeat for the ego. Also, a defeat for grandiose contents and defenses, which are overwhelmed and transformed by an experience of the Self. 2. The fear of the Self and its energies stems from an abandonment fear. A person may have the following attitude: “If I contact all that strength and effectiveness, no one will be able to be with me, I’ll be too powerful and everyone will send me away”. 3. The fear of taking hold of the energies of the Self because they can be so appealing and beautiful that one is certain he will become the object of envy. So, one has to sacrifice or hide the Self to avoid envy’s “evil eye”. The person terrified of envy is not only afraid of envy attacks from the others, even worse, he also hides his prize from himself. VARIETIES OF THE NUMINOSUM 1 As a numinous dream. 2 As a waking vision. 3 As an experience in the body. 4 Within a relationship including the transference/countertransference aspects of psychotherapy. 5 In the wilderness. 6 By aesthetic or creative means. 7 As a synchronistic event. Numinous experience is synonymous with religious experience. Translated into psychological parlance, this means the relatively direct experience of those deep intrapsychic structures known as archetypes.. The archetype is a fundamental organizing principle which originates from the objective psyche, beyond the level of the empirical personality. In the religious literature, what the depth psychologist calls an archetype would be referred to as spirit; operationally they are synonymous. But crucially for the depth psychologist, the archetypes are not only numinous manifestations of the divine, they also play a part in the organization of the personality. Our experience of the transpersonal Self, which is considered to be the totality of the psyche, may also be mediated by means of the effects of one of its constituent archetypes. The Self cannot be thought of as a unitary phenomenon, but rather as the source of all the archetypes, so that any archetypal experience is an experience of some aspect of the Self. These principles of intrapsychic organization do not only produce exotic dream images; as discussed later, they affect development, structure relationships and produce archetypal transferences. [Kohut’s (1971) mirroring and idealizing transferences (see p. 26) are just two examples of instances in which elements of the Self unfold and require a human response.] What is characteristic of all archetypal or numinous experience is its affective intensity, both developmentally and psychotherapeutically. The characteristic affects produced by the archetype provide a clue to its presence, and so will be considered first. FOUR ASPECTS OF THE TRANSCENDENT SELF 1. The Self as the Totality of the Psyche, 1. The Self as an Archetype, 1. The self as a Unconscious, Personification 1. The Self as the Process of the Psyche. of the The Self as the Totality of the Psyche • The self is the totality of everything conscious and unconscious, as well, of everything somatic and psychic. • If the Self consists of unconscious elements than it can only be partially represented in consciousness, either through experiences of wholeness or through symbolic images which represent a wholeness greater than oneself. • Since the Self includes the unconscious as well as the conscious mind, and the unconscious is by definition unknown to consciousness, the greater part of the Self must remain forever unknowable. • Jung regards the symbolic representations of totality which appear in consciousness as indistinguishable from the God-image. He wasn’t saying that “God” and “the Self” are the same thing; what he was trying to express is that religious imagery is concerned with the symbolism of psychic wholeness and that religious aspirations are identical with the goal of individuation. The Self as an Archetype • The Self is both the totality and an archetype within the totality, albeit the central one. • It is the archetype of order, coherence, a sense of agency, affective relational patterns, and integration. • Therefore, it is the archetype of the ego/personal self, and of subjectivity – that is, a basic principle which underlies the experience of a subjective self out of which the ego gradually develops. The Self as a Personification of the Unconscious • The Ego – Self Axis. • Ego develops out of the Self; its development is seen as a progressive emergence and differentiation from the Self (equated with the unconscious). • It is a dialectical relation between the Ego and the Self: “the dialectic between ego and self paradoxically leads to both greater separation and greater intimacy” (E. Edinger, 1960). EGO – SELF SEPARATION EGO – SELF UNION EGO – SELF IN DIFFERENT STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT The Self as the Process of the Psyche • The self is not only the organizing principle within the psyche but the organizing principle of the psyche. • So to speak, it is an archetypal structure which has power to organize its contents, yet it is the structure which is inherent in that which it is organizing. • The Self is both a tendency towards organization (i.e. the process of individuation) and the structure of that organization (the Self as archetype). SELF IMAGES IN PSYCHOTHERAPY Most of the intrapsychic symbols of the Self falls in one of the following four categories: 1. 2. 3. 4. Mandala imagery, Transcendent figures, United opposites, Natural phenomena. 1. Mandala imagery. Mandalas are geometric figures which portray symmetry, wholeness and completion. They are usually combinations of circles or squares, in dreams taking the form of cities, wheels, temples, gardens, spirals, flowers or other natural forms. Often these figures are quartered, and the number four has traditionally been thought to express completion. Jung noticed that this kind of material tends to emerge in the dreams and fantasies of people in crisis. He felt that the appearance of mandalas is the result of the psyche’s tendency to try to restore homeostasis by producing images of order and harmony; they remind us that we have a centre and a protected enclosure. • Experience in practice confirms Jung’s view that their occurrence is soothing in fairly healthy people, especially those who are able to externalize them as paintings, dance or sculptures. But in borderline people in a state of disintegration they do little to prevent or heal the fragmentation of the personal self. • Mandalas also appear prominently in the productions of psychotic people, and Perry (1985) has suggested that this imagery seems to represent an attempt by the Self at reintegrating the disrupted personality. (However, such numinous experiences of the Self are also common precursors of psychosis, reminding us that the Self may be an agent of fragmentation as well as integration.) 2. Transcendent figures. These may be Christ, Tara, Isis, Dionysus, or other deities, a Guru, the Buddha, saint, royalty or anyone sufficiently idealized to be able to carry such intense projections. Interestingly, when such figures appear in dreams, the dreamer may or may not belong to the religious tradition of the particular figure involved. In this way we may discover that our personal myth is located in a tradition that was not necessarily that of our family of origin. It is not uncommon for such figures to appear as waking visions. A woman fell into a reverie while embroidering a cross on a church banner; to her amazement a Jesus-like figure appeared, pushed aside what she was making and gave her another, personal symbol for her own use. The Self does not always respect convention. 3. United opposites. According to Jung (CW 9, ii, 355), elements within the personality that are felt to be in opposition to each other are reconciled and transcended within the Self. The larger psyche harmoniously contains elements that seem conflictual to the individual self. Consequently, in situations in which we suffer from being pulled in apparently irreconcilable directions, the compensatory effect of the Self is to produce dream imagery of opposites united, such as marriage pairs, hermaphrodites, an old person and a child, a winged snake, and so on. These indicate the transcendence of polarity, and prevent consciousness from over-identifying with one side of a conflict. In psychotherapeutic practice this is sometimes an over-optimistic view; we may have to wait an intolerably long time for such material, and it may not appear at all. Resolution then has to occur by means of some other channel, which is usually the therapeutic relationship. 4. The Self may also symbolize itself as awe-inspiring natural phenomena such as wild animals or fish, trees, mountains and oceans. Here the instinctual or organic life of the Self is being stressed. This imagery tends to occur when the individual needs to reestablish contact with this level of being. For modern people, it is hard to imagine a God-image taking such a form, but among pre-technological people such was often the case. Symbols of the Self