Seminar Presentation - National Humanities Center

advertisement

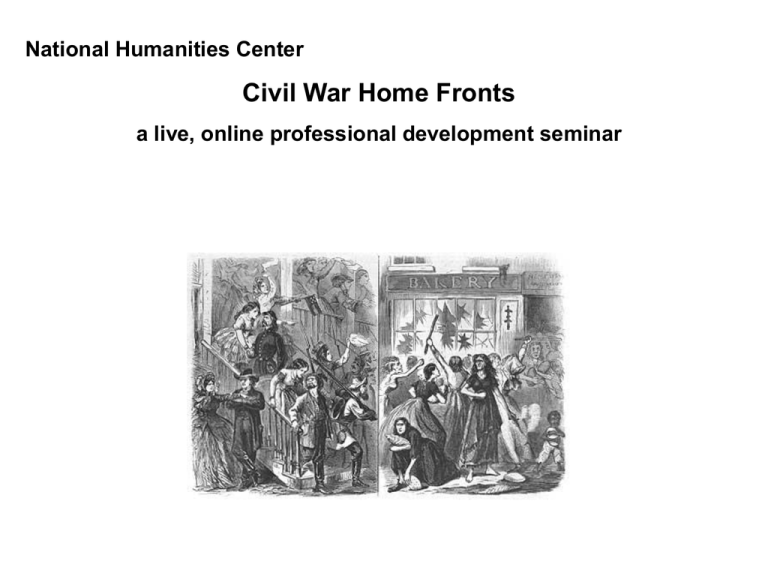

National Humanities Center Civil War Home Fronts a live, online professional development seminar Focus Questions How did the total mobilization of the Civil War affect the Northern and Southern home fronts? What was life like for women on the Northern and Southern home fronts? What was life like for African Americans on the Northern and Southern home fronts? Fitzhugh Brundage National Humanities Center Fellow 1995-96 William B. Umstead Professor of History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill A Socialist Utopia in the New South: The Ruskin Colonies in Tennessee and Georgia, 1894-1901 Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880-1939 Scale of the Civil War When we consider the home front during the Civil War, it is important to take into account the unprecedented scale of the American Civil War. Nothing in the experience of Antebellum Americans prepared them for a war of the magnitude of the Civil War. The only pre-Civil War conflict that was comparable was the Crimea War, fought a few years before the Civil War. Americans, however, had only the vaguest understanding of the carnage of that war, which took place in far-distant Russia, Turkey, and the Baltic region. Scope of War’s Impact Mobilizing for modern war necessarily places great strains on a society, often accelerating changes and magnifying tensions already present in a society. Because the Civil War was long and bloody, its impact was felt in virtually every corner of American society. Civil War Casualties Compared One way to highlight the immensity of the war is to compare and contrast the number of American combatants and casualties in previous wars with the Civil War. Revolutionary War 20,000 regulars served in the Continental Army. An estimated 25,000 American Revolutionaries died during active military service. About 8,000 of these deaths were in battle; the other 17,000 deaths were from disease, including about 8,000 12,000 who died while prisoners of war. The number of Revolutionaries seriously wounded or disabled by the war has been estimated from 8,500 to 25,000. The total American military casualty figure was therefore as high as 50,000. War of 1812 At the beginning of the war, there were 7,000 regulars in the Army. By the end of the conflict the ranks had swollen to almost 40,000. Approximately 2,260 were killed in action and another 4,505 wounded. Approximately 17,000 died from disease. Indian Wars The various Indian wars of the early nineteenth century, including the three Seminole Wars, claimed fewer than 1,000 casualties. At any given time there were perhaps 10,000 regulars engaged in the Indian wars. Mexican War For most Americans at the time of the Civil War, the Mexican War was their most recent experience with war and combat. During the Mexican War, 78,700 soldiers served. Of these 1,733 were killed in battle, and another 13,271 died from disease, etc. 4,152 were wounded. U.S. Civil War Perhaps as many as 4 million men fought in the Civil War. 2.5 million men served in the Union Army. There are no definitive number of the strength of the Confederate States Army. Confederate war department reports recorded 326,768 men in 1861, 449,439 in 1862, and 464,646 in 1863 before declining to 358,692 in 1865. Based on these totals, the total number of men who fought for the Confederacy has been estimated between 1.2 and 1.4 million. U. S. Civil War Of the troops who fought for the Union, 110,070 died in combat and an additional 249,458 of other causes. 275,175 were wounded. Of the troops who fought for the Confederacy, 74,524 died in combat, and 124,000 of other causes. An estimated 137,000 + were wounded while in the ranks. U. S. Civil War In starkest terms, approximately 4 million out of an American population of 31.5 million fought in the war, and perhaps as many as a million of these soldiers died or were wounded. U. S. Civil War To mobilize a population to wage war and to endure casualties in this scale, arguably, was the greatest challenge that Presidents Lincoln and Davis confronted. U.S. Civil War Because of deeply rooted animosity to standing armies in the United States, both the Union and the Confederacy initially had to rely on voluntary support for the war effort. Even when both governments eventually adopted conscription to fill their armies, they insisted that their publics – the home fronts -- enthusiastically supported the war. Response of Women How women in the Union and the Confederacy responded to the war is especially revealing of the pressures of modern war on the home front. Just what were the appropriate roles for women during war? What sacrifices could women be expected to make? To what extent were women expected/allowed to deviate from inherited codes of feminine conduct? What was life like for women on the northern and southern home fronts? • In what capacities were women expected to contribute to the war? How did women justify the roles that they assumed? • In reading Sarah Morgan’s diary, we get an interesting perspective on female Confederate patriotism. Did Morgan distinguish between the expectations of patriotic behavior according to gender? What did she expect of “loyal” southern white women? Of southern white men? And what were her views of the enemy? • To what extent were Gail Hamilton’s views of female sacrifice consonant with Sarah Morgan’s? In other words, were the expectations of feminine patriotism and sacrifice in both the Union and the Confederacy? • How much should we make of the “Bread Riots” in the South? Were they symptomatic of a deep crisis in the patriotism of Confederate women? A Confederate Girl’s Diary The diary entries of Sarah Morgan of Louisiana after the capture of southern Louisiana by Union forces in 1862 offer us a glimpse into how one white southern woman negotiated her conflicting roles as a Confederate, a lady, and an American. Sarah Morgan Dawson, A Confederate Girl’s Diary, 1913 May 9, 1862 If we girls of Baton Rouge had been at the landing, instead of the men, that Yankee would never have insulted us by flying his flag in our faces! We would have opposed his landing except under a flag of truce, but the men let him alone, and he even found a poor Dutchman willing to show him the road! . . . . I wear one pinned to my bosom - not a duster, but a little flag; the man who says take it off will have to pull it off for himself; the man who dares attempt it - well! a pistol in my pocket fills up the gap. I am capable, too. O! if I was only a man! Then I could don the breeches, and slay them with a will! If some few Southern women were in the ranks, they could set the men an example they would not blush to follow. Pshaw! there are no women here! We are all men! Sarah Morgan Dawson, A Confederate Girl’s Diary, 1913 May 14, 1862 Shall I acknowledge that the people we so recently called our brothers are unworthy of consideration, and are liars, cowards, dogs? Not I! If they conquer us, I acknowledge them as a superior race; I will not say that we were conquered by cowards, for where would that place us? It will take a brave people to gain us, and that the Northerners undoubtedly are. I would scorn to have an inferior foe; I fight only my equals. These women may acknowledge that cowards have won battles in which their brothers were engaged, but I, I will ever say mine fought against brave men, and won the day. Which is most honorable? I don't believe in Secession, but I do in Liberty. I want the South to conquer, dictate its own terms, and go back to the Union, for I believe that, apart, inevitable ruin awaits both. It is a rope of sand, this Confederacy, founded on the doctrine of Secession, and will not last many years - not five. Sarah Morgan Dawson, A Confederate Girl’s Diary, 1913 May 9, 1862 If we girls of Baton Rouge had been at the landing, instead of the men, that Yankee would never have insulted us by flying his flag in our faces! We would have opposed his landing except under a flag of truce, but the men let him alone, and he even found a poor Dutchman willing to show him the road! . . . . I wear one pinned to my bosom - not a duster, but a little flag; the man who says take it off will have to pull it off for himself; the man who dares attempt it - well! a pistol in my pocket fills up the gap. I am capable, too. O! if I was only a man! Then I could don the breeches, and slay them with a will! If some few Southern women were in the ranks, they could set the men an example they would not blush to follow. Pshaw! there are no women here! We are all men! Sarah Morgan Dawson, A Confederate Girl’s Diary, 1913 May 17, 1862 O my discarded carving-knife, laid aside under the impression that these men were gentlemen. We will be close friends once more. And if you must have a sheath, perhaps I may find one for you in the heart of the first man who attempts to Butlerize me. I never dreamed of kissing any man save my father and brothers. And why any one should care to kiss any one else, I fail to understand. And I do not propose to learn to make exceptions. Sarah Morgan Dawson, A Confederate Girl’s Diary, 1913 June 10, 1862 It made me ashamed to contrast the quiet, gentlemanly, liberal way these volunteers spoke of us and our cause, with the rabid, fanatical, abusive violence of our own female Secession declaimers. Sarah Morgan Dawson, A Confederate Girl’s Diary, 1913 June 16, 1862 I would put aside woman's trash, take up woman's duty, and I would stand by some forsaken man and bid him Godspeed as he closes his dying eyes. That is woman's mission! and not Preaching and Politics. I say I would, yet here I sit! O for liberty! the liberty that dares do what conscience dictates, and scorns all smaller rules! If I could help these dying men! “A Call to My Country-Women” Gail Hamilton’s “A Call to My Countrywomen” is an equally striking counterpoint to Morgan’s diary. Hamilton exploits every possible rhetorical device to appeal to the women of the North. In what ways does her appeal parrot or differ from the ideas that Morgan expressed in her diary? A CALL TO MY COUNTRY-WOMEN Gail Hamilton (Mary Abigail Dodge) Atlantic Monthly 6 (March 1863) . . . If women, weak or strong, consider that praying is all they can or ought to do for their country, and so settle down contented with that, they make as great a mistake as if they did not pray at all. True, women cannot fight, and there is no call for any great number of female nurses; notwithstanding this, I believe, that, to-day, the issue of this war depends quite as much upon American women as upon American men, and depends, too, not upon the few who write, but upon the many who do not. A CALL TO MY COUNTRY-WOMEN Gail Hamilton (Mary Abigail Dodge) Atlantic Monthly 6 (March 1863) When I read of the Rebels fighting bareheaded, bare-footed, haggard, and unshorn, in rags and filth, fighting bravely, heroically, successfully, I am ready to make a burnt-offering of our stacks of clothing. I feel and fear that we must come down, as they have done, to a recklessness of all incidentals, down to the rough and rugged fastnesses (remote and secluded places) of life, down to the very gates of death itself, before we shall be ready and worthy to win victories. A CALL TO MY COUNTRY-WOMEN Gail Hamilton (Mary Abigail Dodge) Atlantic Monthly 6 (March 1863) Take not acquiescently, but joyfully, the spoiling of your goods. Not only look poverty in the face with high disdain, but embrace it with gladness and welcome. The loss is but for a moment; the gain is for all time. Go farther than this. Consecrate to a holy cause not only the incidentals of life, but life itself. Father, husband, child—I do not say, Give them up to toil, exposure, suffering, death, without a murmur—that implies reluctance. I rather say, Urge them to the offering; fill them with sacred fury; fire them with irresistible desire; strengthen them to heroic will. A CALL TO MY COUNTRY-WOMEN Gail Hamilton (Mary Abigail Dodge) Atlantic Monthly 6 (March 1863) Therefore let us have done at once and forever with paltry considerations, with talk of despondency and darkness. Let compromise, submission, and every form of dishonorable peace be not so much as named among us. Tolerate no coward’s voice or pen or eye. Wherever the serpents head is raised, strike it down. Measure every man by the standard of manhood. By 1863 the rhetoric of sacrifice no longer could assuage the mounting frustration and anger on the home front. When scattered bread riots flared up in Richmond and elsewhere observers and public officials struggled to make sense of the unrest. African American Response Complicating the mobilization for the war in both the North and the South were African Americans, who had their own hopes for the war’s outcome. What insights does A. Jackson’s testimony give us about how blacks in the South responded to the war? Testimony of Alonzo Jackson An African American merchant in South Carolina Yes, about 8 months before Georgetown was occupied by Union soldiers, while I was in the freighting business on my flat boat on Mingo Creek (up Black River) about 30 or 40 miles from Georgetown by water, three white men came near the boat which was at the bank of the river. I was on the boat with only one person, a colored man (in my employ named Henry). As soon as the three white men saw we were colored men they came to the boat and said, “We are Yankee soldiers, and have escaped from the rebel ‘stockade’ at Florence. We are your friends; can’t you do something for us, we are nearly perished.” As soon as I saw them, before they spoke, I knew they were Yankee soldiers by their clothing. They were all private soldiers, so they told me. I invited them to come on the boat and told them I would hurry and cook for them, which I did and gave it to them in my boat. As soon as they entered the boat I shoved off from land and anchored in the creek about sixty feet from shore. I was loading cord wood in my boat when the soldiers came and had completed my load within about four cords. I did not wait to take it all, fearing that someone else might come and catch these Yankees. Neither of the three soldiers ordered me to take them in the boat or made any threats. They did not go in the boat or secure it in any way so that I could not leave it. They only entered the boat after they had told me who they were (as stated) and when I invited them. They were very weak and had no weapons. They had no shoes on. It was then winter weather, and cold. The three Yankees did not suggest anything for me to do for them except to feed them, and wanted to get to the gun boats. They did not know where the gun boats were. I did, and I told them I would take them where they could get to the gun boats unmolested. The soldiers did not pay or give me anything, or promise anything to me at any time, and I have never received anything for any service rendered to any Union soldiers. They did not threaten me or use any violence. They were very friendly and glad to get into such good hands. They showed that they felt very grateful. In about three days’ time we came to “North Island” (about twelve miles from Georgetown) which I then knew was in possession of the Union forces. I did not pass Georgetown by daylight for fear of being stopped by the rebels who had “pickets” all along the shore to stop all boats from going below. In the night I floated with the ebb tide (without being seen) to “North Island.” I got there in the night and landed the three soldiers in my small boat. I showed them the direction to cross the Island so as to get to the gun boats. I knew there were many of the gun boat people on the shore there at that time. I saw the three soldiers go as I directed. I never saw or heard from any of the three soldiers afterwards, but through a colored man named “Miller” (who was on the shore near the gunboats) learned about three soldiers had got to the fleet. “Miller” told me this about two weeks after I took the three soldiers. He saw them and described them so that I was certain he had seen the same three soldiers safe in the protection of the gun boats. Slavery as Cornerstone Given that Vice President Alexander Stephens had described slavery as the cornerstone of the Confederacy in 1861, how and why did Confederate General Cleburne justify emancipating slaves who fought for the Confederacy in 1864? Home Front Fault Lines Cleburne acknowledged the moral “high ground” that the Union occupied with its war against slavery. And yet only a year earlier New York City had erupted in rioting against the draft and African Americans. Just as the bread riots of 1863 drew attention to fault lines in the Confederacy, so too the riots in New York exposed deep divisions there. What were those divisions according to the editorialists of Harper’s Weekly? What was life like for African Americans on the northern and southern home fronts? • Alonzo Jackson’s testimony is very matter of the fact. Yet, the actions he took reveal a great deal about the response of southern African Americans to their circumstances during the Civil War. Is there anything in particular that strikes you as noteworthy or surprising about either Jackson’s actions or his description of them? • Do you think Jackson’s actions are the sort of behavior that prompted Cleburne to offer his proposal for Confederate emancipation? • How different do you think the northern motivation for arming African Americans was than Cleburne’s motivation? In other words, did the same exigencies that drove the North to arm blacks subsequently prod the South to contemplate doing so? How likely was it that blacks would have fought for the Confederacy? • The New York Draft Riots are a conspicuous reminder of how circumscribed “freedom” was for blacks in the North. From the perspective of the editorialists of Harper’s Weekly, what did the riots reveal about New Yorkers? January 2, 1864 COMMANDING GENERAL, THE CORPS, DIVISION, BRIGADE, AND REGIMENTAL COMMANDERS OF THE ARMY of TENNESSEE: GENERAL: We can give but a faint idea when we say it means the loss of all we now hold most sacred— slaves and all other personal property, lands, homesteads, liberty, justice, safety, pride, manhood. It means that the history of this heroic struggle will be written by the enemy; that our youth will be trained by Northern school teachers; will learn from Northern school books their version of the war; will be impressed by all the influences of history and education to regard our gallant dead as traitors, our maimed veterans as fit objects for derision. It means the crushing of Southern manhood, the hatred of our former slaves, who will, on a spy system, be our secret police. The enemy has three sources of supply: First, his own motley population; secondly, our slaves; and thirdly, Europeans whose hearts are fired into a crusade against us by fictitious pictures of the atrocities of slavery, and who meet no hindrance from their Governments in such enterprise, because these Governments are equally antagonistic to the institution. . . . Apart from the assistance that home and foreign prejudice against slavery has given to the North, slavery is a source of great strength to the enemy in a purely military point of view, by supplying him with an army from our granaries; but it is our most vulnerable point, a continued embarrassment, and in some respects an insidious weakness. As between the loss of independence and the loss of slavery, we assume that every patriot will freely give up the latter—give up the negro slave rather than be a slave himself. It [enlisting slaves to fight for the Confederacy] would remove forever all selfish taint from our cause and place independence above every question of property. Harper’s Weekly July 25, 1863 The Draft The leaders and principal actors in the affair were boys—beardless youths of fifteen to eighteen. Behind these, and seemingly operating as a mere reserve force, was a body of men—operatives in foundries and factories, laborers, stablemen, etc. —who did the murdering of policemen, the gutting of houses, the firing of dwellings, etc., after the boys had opened the battle with volleys of stones. In all the crowds there was a fair sprinkling of women, not young, but married women, who were probably roused to fury by the fear of having their husbands taken from them by the draft. This kind of mixed crowd, though often good-humored and apt to be easily managed by a skillful leader, is likewise prone to the wildest excesses of passion and brutality. The boys and men invariably get drunk at an early stage of the proceedings; the women appear to become equally intoxicated with excitement; and all together commit crimes from which every individual in the crowd would probably shrink if he were alone. Such crowds are so cowardly Harper’s Weekly August 1, 1863 The Riots The outbreak was the natural consequence of pernicious teachings widely scattered among the ignorant and excitable populace of a great city; and the only possible mode of dealing with it was stern and bloody repression. Had the mob been assailed with grape and canister on Monday, when the first disturbance took place, it would have been a saving of life and property. Had the resistance been more general, and the bloodshed more profuse than it was, on Thursday, Some newspapers dwell upon the fact that the rioters were uniformly Irish, and hence argue that our trouble arises from the perversity of the Irish race. . . . Turbulence is no exclusive attribute of the Irish character: it is common to all mobs in all countries. It happens in this city that, in our working classes, the Irish element largely preponderates over all others, and if the populace acts as a populace Irishmen are naturally prominent therein. It happens, also, that, from the limited opportunities which the Irish enjoy for education in their own country, they are more easily misled by knaves, and made the tools of politicians, when they come here, than Germans or men of other races. The impulsiveness of the Celt, likewise, prompts him to be foremost in every outburst. . . . An Open Letter MY DEAR FRIEND,—YOU are a German and a Jew, and you have come to make your living in a foreign land, of which Christianity is the professed religion. You have no native, no political, no religious sympathy with this country. You are here solely to make money, and your only wish is to make money as fast as possible. You neither know our history nor understand our Government; but, believing that all men are selfish and mean, nothing is absurder to your mind than the American doctrine of popular government based upon equal rights. You are the material out of which despotisms are made. It is upon such people as you that the King of Prussia counts when he deliberately destroys the constitutional rights of his subjects. And whatever in this country is despotic, mean, and repugnant to the great and fundamental democratic doctrine of equal rights before the law, receives your hearty sympathy and support. The country you left did not regret your coming away; the country in which you trade will not mourn your departure Focus Questions How did the total mobilization of the Civil War affect the Northern and Southern home fronts? What was life like for women on the Northern and Southern home fronts? What was life like for African Americans on the Northern and Southern home fronts? Final slide. Thank you.