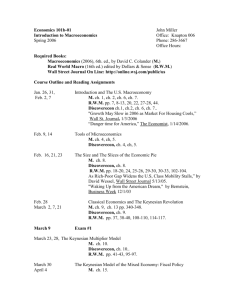

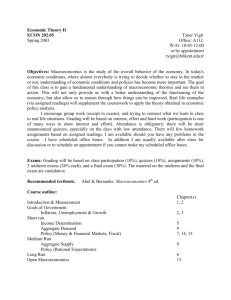

Introduction to Macroeconomics

advertisement

Intermediate Macroeconomics Chapter 8 Money Supply Money Supply 1. 2. 3. 4. Classical Theory of Money Short-run Keynesian View Friedman and the Monetarists Fiscal and Monetary Policy and the Great Depression Intermediate Macroeconomics 1. Classical Theory of Money U.S. long-run relationship Percent change in GDP deflator 8 7 1970s 6 5 1980s 4 3 1990s 2 1960s 1 0 0 2 4 6 8 Percent change in M2 Intermediate Macroeconomics 10 12 1. Classical Theory of Money International, 1993 - 2002 Annual Percent Change in Consumer Price Index 1000 100 10 1 1 10 100 Annual Percent Change in Money Supply Intermediate Macroeconomics 1000 1. Classical Theory of Money Quantity theory of money M•V=P•Q M = money supply (M2) V = velocity of money P = average price level Q = real output P • Q ≡ nominal GDP ≡ national income Intermediate Macroeconomics 1. Classical Theory of Money Assumption 1: Velocity of money is constant Velocity of Money 10 Velocity based on M1 8 6 4 Velocity based on M2 2 0 1959 1969 1979 1989 Source: Velocity of money = U.S. nominal GDP (www.bea.gov) divided by U.S. money supply (www.federal reserve.org) Intermediate Macroeconomics 1999 1. Classical Theory of Money Assumption 2: Full-employment output • Economy is always at full-employment output. • Q constant at full-employment output Since by assumption 1: V is constant: M•V=P•Q A 1% increase in money supply, M, leads to a 1% increase in the average level of prices, P. Intermediate Macroeconomics 1. Classical Theory of Money Aggregate supply and aggregate demand Long-run = Full-employment Aggregate Output Supply 35 Average Price Level 30 25 20 15 10 Aggregate Demand Increase in Average Level of Prices Increase in Money Supply AD1 (M1) AD0 (M0) 5 0 0 2 4 Intermediate Macroeconomics 6 8 10 12 Real Output 14 16 18 2. Short-run Keynesian View Prices and Velocity To escape the classical assumption that output was always at full-employment Keynes’ assumed prices were “sticky”. But, the quantity theory of money then implies an increase in money supply with velocity constant would lead to an increase in output: M•V=P•Q Keynes also had to show that velocity was not constant. Intermediate Macroeconomics 2. Short-run Keynesian View Real money demand M = Real money balances P = Purchasing Power Quantity theory real money demand: M=1 Q P V With velocity, V, constant, real money demand is a function output only – hence, classical quantity theory is also called transactions demand for money. Intermediate Macroeconomics 2. Short-run Keynesian View Speculative demand for money Keynes proposed real money demand is also a function of interest rates: M=k•Q–h•i P Velocity of money no longer constant Intermediate Macroeconomics 2. Short-run Keynesian View Liquidity trap • When the interest rate is so low (and the price of bonds is high) people are willing to hold onto money expecting future interest rates to be higher (and bond prices lower). • Changes in money supply have no effect on interest rates or the economy. Intermediate Macroeconomics 3. Friedman and the Monetarists • Long and variable lags • Policy rules versus discretion Intermediate Macroeconomics 3. Friedman and the Monetarists Long and variable lags • Recognition lag • Implementation lag • Response lag Intermediate Macroeconomics 3. Friedman and the Monetarists Long and variable lags Because of information problems and lags between the implementation of policies and their effects, the scope for monetary policy should be restricted. Intermediate Macroeconomics 3. Friedman and the Monetarists Policy rules versus discretion • Monetarists - the Fed should be bound to fixed rules. In particular, a money growth rule: the growth rate of money supply should equal the long-run growth rate of real GDP, leaving the price level unchanged. • Keynesians - the Fed should have discretion in conducting policy because of the instability of the velocity of money and the potential instability of markets. Intermediate Macroeconomics 3. Friedman and the Monetarists Rules Under rules, the central bank is required to follow a simple predetermined rule for money supply Benefits: - Better household forecasting - Increased monetary discipline Costs: - Monetary policy can not adjust to economic shocks Intermediate Macroeconomics 3. Friedman and the Monetarists Discretion Under discretion, the central bank is expected to monitor the economy and use monetary policy to achieve macroeconomic goals Benefits: - Monetary policy can adjust be proactive, adjusting to economic shocks Costs: - Harder for households to make good forecasts - Fed has incentives to deviate from announced policies Intermediate Macroeconomics 4. Policy and the Great Depression Stock Market Dow Jones Industrial Average 400 350 Sep - Nov 1929 37% decline 300 250 Aug - Nov 1929 37% decline 200 150 100 50 Between Sep 1929 and Jun 1932 the stock market fell 85% 0 Jan-28 Jan-30 Jan-32 Jan-34 Jan-36 Jan-38 Jan-40 Intermediate Macroeconomics Source: National Bureau of Economic Research, Macro History Database, http://www.nber.org/databases/macrohistory/contents/chapter11.html 4. Policy and the Great Depression Factory Employment Production Index, 1923-1925 = 100 Index of Factory Employment 1923 - 1925 = 100 250 Manufacturing employment began falling in March 1929 200 150 100 50 0 1925 1927 1929 Machinery Clay and Glass Products 1931 1933 1935 Paper and Printing Lumber and Products 1937 1941 Iron and Steel Products Source: National Bureau of Economic Research, Macrohistory: VIII. Income and Employment, http://www.nber.org/databases/macrohistory/contents/chapter08.html Intermediate Macroeconomics 1939 4. Policy and the Great Depression Income tax rate on highest bracket 100 Highest tax bracket Income tax rate, percent 90 1931 1932 Lowest Bracket 1.125% 4.0% Highest Bracket 25.0% 63.0% 80 70 60 50 40 30 Lowest tax bracket 20 10 0 1913 1922 1931 1940 1949 1958 1967 1976 1985 1994 Source: Internal Revenue Service, Personal Exemptions and Individual Income Tax Rates, 1913-2002, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/02inpetr.pdf Intermediate Macroeconomics 4. Policy and the Great Depression Money Supply Money Supply (billions) $60 $50 $40 $30 $20 Bank Holiday March 1933 $10 $0 Jan-29 Jan-30 Jan-31 Jan-32 Jan-33 Jan-34 Jan-35 Jan-36 Source: National Bureayu of Economic Research, Macro History Database, series M14144a <http://www.nber.org/databases/macrohistory/contents/chapter14.html> Intermediate Macroeconomics Jan-37 Jan-38