document

advertisement

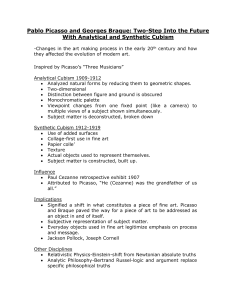

Cubism Cubism Continued the reaction against past traditions Purpose was to give an abstract, multiple, mathematical view of reality. Artists break up space into geometric shapes and forms Subject matter is broken up, analyzed, and then re-assembled in abstract form Objects were radically fragmented, to see several sides simultaneously More "abstract" than previous styles. Form is stressed over content Subjects are often fruit, cars, still life, musicians Use of 2-D "flat" space with little depth and unemotional colors Developed the use of collage Pablo Picasso, Violin and Grapes “It’s not a reality you can take in your hand. It’s more like a perfume. The scent is everywhere but you don't quite know where it comes from.” Violin & Grapes The “King” of modern art; inventedCubism -could draw before he could talk. His art was always biographical: “The paintings are the pages of my diary.” He went through the blue period, rose period, African American period and into Cubism. He liked to break up space into jagged planes without order. He would smash bodies to bits and reassemble them on a place as “fields of broken glass” 'Violin and Grapes' is quite a dark painting. Picasso used different shades of brown. The violin consists of different planes, it is fragmentary but the characteristic features are preserved. This painting contains different forms, such as round and angular planes and distinct shapes of a violin and grapes. The fiddlestick, the strings, the case and the neck of the violin are clearly distinguished. The grapes are in the right bottom corner of the painting. They are constituted by a number of small circles. The case is broken up in different peaces and every peace is shown in a different angle, a different direction. Some parts show a very realistic imitation of grain of wood, such as the neck and some parts of the case of the violin. Other parts are obviously painted and strongly contoured. It is possible to distinct various wooden parts in the painting on which the violin and grapes lie. The grapes make the painting less stiff, they are in contrast to the abstract violin. Picasso, Man With a Guitar” Man with a Guitar He created these using the rhythm and freedom of music to create his first Cubist guitar paintings. Despite its technicalities, the music’s (Catalan dance music) freedom was designed to elicit fun. The Catalan culture embraced the sardana because of its free and convivial qualities. The dance was open to all ages and meant to promote enjoyment (Pérez 40). Painted during Picasso’s third summer in Céret, the painting again has its foundation in the geometry, stemming from the sardana’s rhythm. Picasso positioned rectangles to form the man’s body and the neck of the guitar. Crescents and ovals form the man’s face, hat brim, and the guitar’s body. Picasso built off this structure by disregarding boundaries for the objects, paralleling the continual improvisation in the sardana. The man and the guitar blend into each other, perhaps Picasso’s illustration of music’s ability to capture and influence a person – just as the Catalan music did to Picasso. The colors create vibrancy, and here Picasso finally escaped the dreariness in color that carried over from his Blue Period. Man with Guitar convey an upbeat mood that resembles the enjoyment promoted by the sardana. It can be argued that the liveliness of the Catalan music inspired Picasso to flourish Cubism with colors and more distinction, creating a brighter and less monotonous work Picasso, Woman with Pears Women were his chief inspiration. Comment on the colors. Comment on the mood or tone of this painting. Picasso, Girl Before a Mirror Girl Before a Mirror Girl Before a Mirror shows Picasso's young mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter, one of his favorite subjects in the early 1930s. Her white-haloed profile, painted in a smooth lavender pink, appears calm. But it merges with a more roughly painted, frontal view of her face—a crescent, like the moon, yet intensely yellow, like the sun, and "made up" with a gilding of rouge, lipstick, and green eye-shadow. Perhaps the painting suggests both Walter's day-self and her night-self, both her tranquillity and her vitality, but also the transition from an innocent girl to a worldly woman aware of her own sexuality. It is also a complex variant on the traditional idea of vanity—the image of a woman confronting her mortality in a mirror, which reflects her as a death's head. On the right, the mirror reflection suggests a supernatural x-ray of the girl's soul, her future, her fate. Her face is darkened, her eyes are round and hollow, and her intensely feminine body is twisted and contorted. She seems older and more anxious. The girl reaches out to the reflection, as if trying to unite her different "selves." The diamond-patterned wallpaper recalls the costume of the Harlequin, the comic character from the commedia dell'arte with whom Picasso often identified himself—here a silent witness to the girl's psychic and physical transformations. (www.moma.org) Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon Les Demoiselles d'Avignon One of the most important works in modern art. The painting depicts five naked prostitutes in a brothel; two of them push aside curtains around the space where the other women strike seductive and erotic poses. Their figures are composed of flat, splintered planes rather than rounded volumes, their eyes are lopsided or staring or asymmetrical, and the two women at the right have threatening masks for heads. The space, too, which should recede, comes forward in jagged shards, like broken glass. In the still life at the bottom, a piece of melon slices the air like a scythe. The faces of the figures at the right are influenced by African masks, which Picasso assumed had functioned as magical protectors against dangerous spirits: this work, he said later, was his "first exorcism painting." A specific danger he had in mind was life-threatening sexual disease, a source of considerable anxiety in Paris at the time; earlier sketches for the painting more clearly link sexual pleasure to mortality. In its brutal treatment of the body and its clashes of color and style (other sources for this work include ancient Iberian statuary and the work of Paul Cézanne), Les Demoiselles d'Avignon marks a radical break from traditional composition and perspective. Picasso, Three Musicians Three Musicians At the left of a bare and boxlike space, a masked man, Peirrot, plays the clarinet. At the right, a singing monk holds sheet music. And in the center, strumming a guitar, is a Harlequin, in Picasso's art often a stand-in for the artist himself. Pierrot and Harlequin are stock characters in the old Italian comic theater. The painting, then, has a whimsical side, epitomized by the near-invisible dog: its head is about halfway up the canvas on the left, one of several subtle browns, and we can also make out front paws, a hind leg, and a jaunty tail popping up between Harlequin's legs. Overall, though, the work's somber background and large size make the musicians a solemn, even majestic trio. The intricate, jigsaw-puzzle-like composition sums up the Synthetic Cubist style, the flat planes of unshaded color recalling the cutout and pasted paper forms with which the style began. These overlapping shapes are at their most complex at the center of the picture, which is also where the lightest hues are concentrated, so that an aura of darkness surrounds a brighter center. Along with the frontal poses of the figures, this creates a feeling of gravity and monumentality, and gives Three Musicians a mysterious, otherworldly air. (www.moma.org) Georges Braque, The Harbor The Harbor Braque's paintings of 1908–1913 began to reflect his new interest in geometry and simultaneous perspective. He conducted an intense study of the effects of light and perspective and the technical means that painters use to represent these effects, appearing to question the most standard of artistic conventions. In his village scenes, for example, Braque frequently reduced an architectural structure to a geometric form approximating a cube, yet rendered its shading so that it looked both flat and three-dimensional. In this way Braque called attention to the very nature of visual illusion and artistic representation. Beginning in 1909, Braque began to work closely with Pablo Picasso who had been developing a similar approach to painting. The invention of Cubism was a joint effort between Picasso and Braque, (www.wikipedia.org) \ A work painted from memory in the spring of 1909: there is in the handling of the sky in the Harbor in Normandy, and indeed throughout the whole picture, a much greater emphasis on the richness of the pigment itself than there is in contemporary works by Picasso. The forms of lighthouses and boats, while almost toy-like in their basic simplicity, are developed internally in terms of a large number of planes or facets, and since the sky receives the same treatment, the painting resolves itself into a mass of small, shifting planes, jointed together or hanging behind each other in shallow depth. Out of this, forms emerge, solidify, and then disintegrate again as the spectator turns his attention back from the individual forms to the painting as a whole. Uberto Boccioni, Dynamism of a Soccer Player Soccer Player In combining Picasso's fragmentation of form with Seurat's pointillist painting technique, Dynamism of a Soccer Player (1913, Museum of Modern Art, New York City) by Umberto Boccioni is typical of futurism and cubism. But the most noticeable feature of Boccioni’s many-legged soccer player is its depiction of motion. To achieve this sense of motion, the futurists drew upon sequential photographs of human movement by photographer Eadweard Muybridge and scientist Etienne-Jules Marey. "A galloping horse," the futurists proclaimed, "has not four legs but twenty.“ Like Léger, the futurists believed that a new society could be built only if citizens sacrificed their individuality for the good of the larger group. The new ideal human being suggested in Boccioni's painting would be more machine than man: strong, energetic, impersonal, even violent. Max Weber, Chinese Restaurant Chinese Restaurant This painting by Max Weber was inspired by a visit to a Chinese restaurant. It's like an exploded jigsaw puzzle in which you can still make out some of the pieces. Gold and black squares cover the lower half of the painting; this is the linoleum on the restaurant's floor. Red and gold, the traditional color scheme of a Chinese restaurant, predominate. Throughout, Weber incorporates textures and patterns taken from elements of the restaurant's decor. Look at the center of the image: fragments of faces give a sense of the crowded interior and the hustle and bustle of the waiters. Some of the faces repeat, in an arrangement that looks like stop-action photography, where a range of motion is broken down into a series of single moments. The resulting sense of movement re-creates the accelerated pace of modern life. When this painting was made, in 1915, Chinese restaurants were exotic novelties in New York. The fragmentation of this image refers to another novelty, too: it calls up the techniques of Cubist painting, which was all the rage in Europe. Cubism gave Weber the technique he needed to present a new world in a new way. He attempted to capture the powerful rhythms of the streets in abstract form. Wifredo Lam, The Jungle The Jungle Masked figures simultaneously appear and disappear amid the thick foliage of sugarcane and bamboo. The multi perspective creation of these figures mirrors Cubist vocabulary, while the fantastical moonlit scene around these monstrous beings—half man, half animal—emerging out of a primeval jungle evokes the realm of the Surrealists. In his desire to express the spirit of Afro-Cuban culture, in particular that of the uprooted Africans "who brought their primitive culture, their magical religion, with its mystical side in close correspondence with nature," Lam reinforces the Surrealist aspect of this work. Born in Cuba, Lam spent eighteen years in Europe (1923–41), which deeply affected his artistic vision. While there, he befriended Pablo Picasso and also established himself as an integral member of the Surrealist movement. The artistic and cultural traditions of Lam's homeland and Europe converged when he returned to Cuba and renewed his familiarity with its light, vegetation, and culture. In The Jungle the presence of the woman-horse, who in Afro-Cuban mysticism refers to a spirit in communication with the natural world, mirrors Lam's own confrontational dialogue with the so-called primitive interests expressed in advanced European painting. His work is an example of this confluence of two cultures.