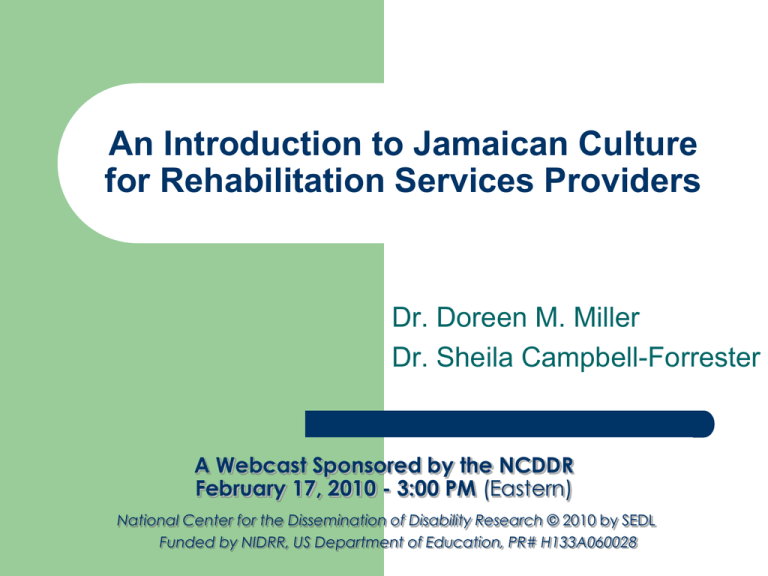

An Introduction to Jamaican Culture for Rehabilitation Services

advertisement

An Introduction to Jamaican Culture for Rehabilitation Services Providers Dr. Doreen M. Miller Dr. Sheila Campbell-Forrester A Webcast Sponsored by the NCDDR February 17, 2010 - 3:00 PM (Eastern) National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research © 2010 by SEDL Funded by NIDRR, US Department of Education, PR# H133A060028 Introduction The purpose of this presentation is to provide an overview of Jamaican culture and its influence on disability issues. 2 Introduction The presentation will address the following: •History and reasons for emigration to the United States •Jamaicans' concept of disability •Views on acquired and lifelong disabilities •Concept of independence •Jamaican culture 3 Introduction 4 •Typical patterns of interactions between consumers and rehabilitation service providers, • Family structure, • Role of community and gender differences in service provision, eating habits, • Recommendations to rehabilitation service providers • Ways in which service providers can become more familiar with the culture. Geography 5 The country of Jamaica is a West Indian island located near the center of the Caribbean Sea. It is among the group of islands that comprise the Greater Antilles (the others are Cuba, Haiti, Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico) and is the largest of the English–speaking islands in the region. Jamaica is 90 miles south of Cuba, 100 miles west of Haiti and 579 miles from Miami. Geography 6 Approximately the size of Connecticut, Jamaica has an area of 4,411 square miles and is 146 miles long. The breadth of the island varies from 22 miles at its narrowest point to 51 miles at the widest. Rugged chains of mountains extend from east to west. The Blue Mountains include the highest point on the island, a summit of 7,402 feet. Low elevations form a costal belt around the island but approximately two thirds of the landmass lies 1000 feet above MAP 7 Population 8 In 2004, the Statistical Institute of Jamaica reported that there were 2.8 million people living on the island. Of this number, 700,000 lived in the corporate area of the capital, Kingston and the city of St. Andrew). Montego Bay, the second largest city, had a population of approximately 85,503. – Median age – Males 26.2, Females 27.6, Total 26.8 Population 9 The ethnic composition of Jamaica reflects the historical legacy of African enslavement. Various historical and sociological reports suggest that most of the Africans taken to Jamaica were from the West African coast and later from Angola and the Congo. Although African slaves in Jamaica were from among a variety of ethnic groups, they were predominantly Coromanties, Eboes and Mandingoes. Population 10 The cessation of the slave trade precipitated a need for new sources of labor to maintain the sugar estates. To meet the demand for labor, East Indian immigrants came to Jamaica in 1842. In 1854, Chinese immigrants were added. Even with the presence of Indians and Chinese, the need for workers remained high. In 1869, East Indian indentured servants were introduced. Today, the ethnic composition of Jamaica is as follows: African descent 90.9%, East Indian 1.3%, white 0.2 percent, Chinese 0.2%, mixed 7.3% and other 0.6%. Government Executive Branch – – Legislative Branch – – – Supreme Court Court of Appeals Political Parties – 11 Senate House of Representatives Judicial Branch – Queen Elizabeth II Governor General – – Jamaica Labor Party (JLP) National Democratic Movement (NDM) People’s National Party (PNP) Education 12 Literacy rate is 87.9% for general population Males’ literacy rate is 84.1 Females’ literacy rate is 91.6 Educational System—based on British system Level of education for individuals with disabilities – 75% Primary level as highest level of education – 10% Secondary education – 0.4% University education (based on 2004 statistics from World Fact Book-Jamaica) Total number of individuals with disability 111,114 Economy 13 The economic system is sustained by tourism and bauxite/alumina Other industries include textiles, clothing, light manufacturing, rum, cement, paper, chemical products, telecommunications and agro processing. Agricultural products such as bananas, coffee and citrus Economy 14 Labor Force—includes agriculture 21%, industry 19%, and services 60%. Unemployment Rate – 15.9% general population 14% of the population of individuals with disabilities had a job – Employment for males 19.5%, females 8.8% Religion Jamaicans are predominately Christian with small numbers of Hindu, Muslim, Jewish, Bahai and African Caribbean religious groups. – – – Rastafarians constitute one of the most famous religious groups. – 15 61.3% Protestants 4% Catholics 5.5% Anglicans Many are reported to live Brooklyn National Holidays 16 Independence Day is the most celebrated event (August 6, 1962) National Heroes Day (October 17) Christmas New Years Easter Labor Day National Symbols 17 National Flag National Symbols 18 Crest History 19 Early settlers were the Arawaks In 1494 Columbus claimed the island for Spain In 1665, the British drove out the Spaniards and the island was ceded under the Treaty of Madrid. In 1834, slavery was abolished Independence from British rule August 6, 1962 History of Immigration There were three waves of immigration to the United States – – – 20 The first wave took place between 1900 and 1920 bringing a modest number of immigrants The second wave and weakest wave occurred between 1930 and mid-1960s. The McCarranWalter Act reaffirmed and upheld a quota bill which allowed only 100 Jamaicans in the U.S. each year The final and largest wave of immigration began in 1965 and continues to the present. History of Immigration 21 Approximately one million Jamaican immigrants live in the United States (between 186,000 to 600,000 live in New York). Jamaicans are the largest group from the English speaking Caribbean History of Immigration 22 The migration from Jamaica was so large that it became a national crisis (brain drain) resulting in an acute shortage of skilled workers and professionals such as doctors and nurses (about 15% of population left the country in the 1980s). Cultural Concept of Disability Cultural concepts that influence views of disability and illness originate in religious beliefs related to Christianity and Afro– Christian sects such as Pocomania. Major beliefs that may have an influence on the way Jamaicans view disability: – – – 23 – – Disability is a punishment for wrongdoing Obeah or Guzu Evil Spirits Ghosts or Duppies Natural Causes Cultural Concept of Disability 24 These belief systems are entrenched in Jamaican society. They have played a major role in shaping the attitudes toward disability and delayed the development of a comprehensive national rehabilitation program. Professionals and the educated middle class tend to hold a strong belief that disability is a result of sin. Stigma and Disabilities 25 The stigma related to disability in the case of children is often directed toward the parent and not the child. The parent is seen as culpable for the child’s disability, i.e., having a child with a disability is punishment for a sin or wrong committed by the parent or ancestor. Stigma and Disabilities 26 Some disabilities carry more stigma than others. For example, cognitive or mental disabilities have the greatest stigma attached. Concept of Independence 27 Jamaicans see themselves as independent thinkers. They take pride in making their own decisions and controlling their own destiny. Many object to others telling them what they "should," "ought" or "must" do. They reject authority when they believe that their intellectual capacity to act on their own behalf is being disregarded or when the authority figure is perceived to be condescending. Concept of Independence 28 Intellectual condescension is a pet peeve of many. Those who are unable to read are particularly sensitive to patronizing intellectual behavior and are not afraid to confront those who disregard their capacity to think. One might say, "mi can't read but mi a no fool, mi know wa mi a do." (I can't read, but I am not a fool, I know what I am doing). Jamaicans often describe themselves as very assertive and not easily dominated. Rehabilitation Service Delivery 29 In general, traditional service delivery in Jamaica is limited, and strong governmental interest is a recent development. Increased interest in the rehabilitation needs of Jamaicans with disabilities occurred as a result of the World Health Organization's (WHO) International Year of the Disabled Person (IYDP), observed in 1981. The commemoration of the International Year of the Disabled Person served to galvanize grassroots efforts to improve the quality of life for Jamaicans with disabilities, highlight the unique needs of citizens with disabilities and harness governmental support. Gender Differences 30 Women tend to take the leadership role in securing and utilizing services for themselves and their families. If a family member is ill, it is the woman who researches available resources and make arrangements to get the person to the doctor or other medical professional, and women are more inclined to seek service for themselves than are men. Gender Differences Men sometimes engage in denial of their own needs that may result in remedial rather than preventative services. As the chief breadwinners, they are reluctant to lose time and money from work to seek medical help. – – – 31 The denial of needs may also be related to the desire to appear "manly" and strong. Going to the doctor for what appears to be a minor illness is sometimes perceived to be a weakness. Sense of duty and responsibility to provide for the family Interaction Between Consumers and Rehabilitation Service Providers 32 Interaction between consumers and service providers may be influenced by the source of referral. Consumers who are referred by the medical profession will be apt to use the resources because physicians are among the authority figures of the society. Rapport building with physician-referred consumers is often easier because of their desire to comply with the doctor's instruction. Interaction Between Consumers and Rehabilitation Service Providers 33 Personal pride also can hamper the relationship between consumers and service providers. Some Jamaicans resist the use of public assistance because they are embarrassed by dependence on governmental or –poor relief– support. In an effort to maintain dignity and avoid being labeled ‘indigent,’ some will remain in dire need. Role of the Community 34 Community involvement in rehabilitation is limited, but increasing public awareness through media promotion is helping to educate the community about issues faced by people who are physically or mentally challenged. Limited input from the community is particularly poignant as it relates to employment of people with disabilities. Most people with disabilities are employed in the governmental work force. The private sector has not yet become a major partner in providing employment. Recommendations for Providing Rehabilitation Services to Jamaicans 35 Greetings or acknowledgment of an individual's presence is an important cultural value. The titles of Miss, Mr., Mrs., Doctor before one's name is important. If you visit a Jamaican office or observe people in social interaction, a title is always attached to a name. Recommendations for Providing Rehabilitation Services to Jamaicans 36 Jamaicans pride themselves on being able to handle their own problems, so it is important to ensure that service delivery environments are supportive of this value Jamaicans are very proud and will go to great lengths to maintain their dignity. Recommendations for Providing Rehabilitation Services to Jamaicans 37 Privacy is highly valued, so discreet and confidential treatment of information is important. Caring for a family member is often an obligatory role. If someone is in the hospital, it is not unusual for family members to insist on providing routine care similar to the role of nurses. Recommendations for Providing Rehabilitation Services to Jamaicans 38 Family members have strong kinship bonds, which might appear unhealthy to some professionals. Providers should refrain from dismantling these bonds, particularly when a family member is ill or disabled. An aunt or uncle might accompany a child to the doctor or other service delivery agency. That aunt or uncle should be treated with the respect of a parent. Recommendations for Providing Rehabilitation Services to Jamaicans 39 Appointments should be made as convenient as possible because Jamaicans have a strong work ethic and will miss an appointment before missing work. Treat the elderly with respect. Voice tone, physical handling (e.g. manipulation of limbs) and instructing the elderly should be done with care and sensitivity. Recommendations for Providing Rehabilitation Services to Jamaicans 40 Jamaicans have a strong antipathy toward the placement of elders or ill family members in nursing homes. Jamaicans place a high value on the intellect, therefore information regarding cognitive dysfunctions should be presented with tact and sensitivity. Recommendations for Providing Rehabilitation Services to Jamaicans 41 Personal information is considered to be just that, so information gathering can be a tedious process. At the beginning, be sure that the client knows your reason for asking for personal information and how the information will be used. Listen carefully to understand what is being said. While English is the language spoken in Jamaica, most Jamaicans, especially the less educated, speak Jamaican Patois. Recommendations for Providing Rehabilitation Services to Jamaicans 42 Acknowledge religious expressions of patients. Most Jamaicans are very religious and they see God as their spiritual refuge and strength in times of crisis. Network with Jamaica professionals in the field of rehabilitation who might serve as informal consultants/advocates on behalf of those Jamaicans receiving rehabilitation services. Suggestions for Becoming more Familiar with Jamaican Culture 43 Be curious and willing to learn about other people and their way of life. Read Jamaican newspapers, novels and explore the Internet as a medium for listening to Jamaican radio stations to gain better insight into their way of life. Recognize that Jamaicans bring with them a cultural history and a strong national identity based on their cultural experience. Remember that "one size does not fit all" when it comes to culture. Refrain from imposing American culture on Jamaicans because many will resent it. Suggestions for Becoming more Familiar with Jamaican Culture 44 Ask when in doubt. Most Jamaicans are proud of their country and are happy to talk about it. Be both a teacher/counselor and a student. The same goes for the client. Learning about each other is a "two way street." Learn the symbols and meanings in the culture (national emblems) and the importance of national icons (national heroes). They provide insights into how the collective identity and consciousness of the country were developed. Suggestions for Becoming more Familiar with Jamaican Culture 45 Examine personal biases and stereotypes against Jamaican immigrants in the United States. Examine personal religious beliefs and, when possible, create a safe space for consumers to express their own. Celebrate your own culture and heritage, but be open to the differences between people. Respect, rather than judge, the cultural background of others. Conclusions 46 If providers remain open to the culture of this group, they can provide holistic rehabilitation services to Jamaican consumers. Informing themselves about the differences and similarities between Jamaicans and the dominant culture will help providers step beyond cultural barriers and provide the quality of service that reflects the fundamental principles of American rehabilitation. References 47 Belgrave, F.Z. and Walker, S. (1991). Differences in Rehabilitation Service Utilization Patterns of African Americans and White Americans with Disabilities. Future Frontiers in the Employment of Minority Persons with Disabilities: Proceedings of the national conference. Washington: The Committee 25–29. Black, C.V. (1997). History of Jamaica. Kingston, Jamaica: Longman. CIA (2004). The World Factbook. Retrieved June 1, 2009 from http://www.travlang.com/factbook/geos/jm.html Dechesnay, M. (1986). Jamaican Family Structure: The Paradox of Normalcy. Family Process, 25, 293–300. Fiest–Price, S. and Ford–Harris, D. (1994). Rehabilitation Counseling: Issues Specific to Providing Services to African American Clients. Journal of Rehabilitation, 60(4), 13–19. Gardner, M., Bell, C., Brown, J., Wright, R., Gooden, N., & Brown, K. (1993). Breaking the Barrier. Kingston, Jamaica: Jamaica Council for the Handicapped, Ministry of Labour & Welfare. Gleaner Company. (1995). Geography and History of Jamaica. Kingston, Jamaica: Gleaner Company Limited. References 48 Harley, D.A. and Alston, R.J. (1996). Older African American Workers: A Look at Vocational Evaluation Issues and Rehabilitation Education Training. Rehabilitation Education, 10(2&3), 151–160. Heinz, A. and Payne–Jackson, A. (1997). Acculturation of Explanatory Models: Jamaican Blood Terms and Concepts. Middle Atlantic Council of Latin American Studies Latin American Essays, 11 (April), 19. Jamaica Information Service. (2000). What is our National Heritage? Jamaica Information Service. Leavitt, R. (1992). Disability and Rehabilitation in Rural Jamaica. London and Toronto: Associated University Press. Lowe, H.I.C. (1995). Jamaican Folk Medicine. Jamaica Journal, 9, 2–3. McGoldrick, M., Pearce, J.K., & Giordana, J. (1982). Ethnicity & Family Therapy, 3–30. Guilford Family Therapy Series. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. References 49 Morrish, I. (1982). Obeah, Christ and Rastaman. Cambridge: James Clarke. Murrell, N. S. (2009). Jamaican Americans. Retrieved June 1, 2009 from http://www.everyculture.com/multi/Ha-La/JamaicanAmerican.html National Advisory Council on Disability. (2000). National Policy for Persons with Disabilities. Jamaica: National Advisory Council on Disability. NUA Internet Survey of Online Users in Latin America (2001). Planning Institute of Jamaica. (2000). Economic and Social Survey Jamaica 1999. Kingston, Jamaica: Planning Institute of Jamaica. Schaller, J., Parker, R. and Garcia, S.B. (1998). Moving toward culturally competent rehabilitation counseling services: Issues and practices. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 29(2), 40–48. Statistical Institute of Jamaica. (2000). Demographic Statistics. Kingston, Jamaica: Statistical Institute of Jamaica. References 50 Statistical Institute of Jamaica. (1998). Statistical Yearbook of Jamaica. Kingston, Jamaica: Printing Unit. Superintendent of Documents. (1999). The World Factbook. Pittsburgh, PA: National Technical Information Service. Virtue, E. (1999). Only the brave stay here. The Gleaner. 8A– 11A. Walker, S., Belgrave, F.Z., Bauner, A.M., Nicholls, R.W. (1986). Equal to the Challenge Perspectives, Problems, and Strategies in the Rehabilitation of the Nonwhite Disabled. Bureau of Educational Research, School of Education. Washington, DC: Howard University. Walker, S., Belgrave, F.Z., Nicholls, R.W., Turner, K.A. (1991). Future Frontiers in the Employment of Minority Persons with Disabilities. Washington DC: Howard University, Research and Training Center. Epidemiology, Treatment Care and Support of HIV in Jamaica Dr. Sheila Campbell-Forester Chief Medical Officer Ministry of Health 51 Presentation Outline Overview of the Epidemic Jamaica’s response to Treatment Care and Support for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) Major challenges to achieving universal access in treatment Key recommendations in moving forward 52 Overview First case of HIV imported into Jamaica in 1982 Very little was known about the behaviour of the virus. The only message we had was that “AIDS kills”. Stigma and discrimination – a challenge The absence of adequate treatment, care and support for PLWHA. 53 Jamaica Annual AIDS Case Rates in Jamaica, St. James & Kingston/St. Andrew (Rate per 100,000 Population) 1982 - 2007 KSA STJ Jamaica Rate per 100,000 pop. 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 KSA '82 '83 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.3 2.6 1.2 STJ Jamaica '85 '86 '87 0 0 '88 '89 3 '90 '91 '92 5.3 6.1 11.7 9.4 1.8 3 '93 '94 '95 '96 '97 '98 '99 '00 '01 '02 '03 '04 '05 '06 '07 13 21.2 32.9 28.8 33.5 38.7 54.6 55.7 50.6 53.7 61.2 57.7 68.9 60.5 55.3 8.4 13.1 17.3 43.6 57.3 44.8 62.1 55.6 71.7 76.1 92.6 89.5 103 92.5 112 97.2 75.9 0.1 0.3 1.4 1.4 2.6 2.8 5.8 5.4 8.8 13.5 20.6 19.7 24.5 25.9 35.9 35.2 36.1 37.9 40.5 42.1 50.7 44.4 41.3 54 HIV/AIDS IN JAMAICA Sero-prevalence among adults 1.6% Estimated No. with HIV/AIDS 27,000 Est. No. unaware of HIV status 18,000 No. of persons in need of ARV 6-7000 No. of persons currently on ARV >5,500 55 A Comprehensive Response Treatment, care and support a key strategic line for Jamaica towards achieving universal access by 2010 Prevention is critical to success and this includes implementation of behaviour change strategies with their foundation in knowledge, attitudes and practices. 56 A comprehensive response A study in 2008, demonstrated that there was no knowledge change between 2004 and 2008 in the 24-59 age group but there was a decline in knowledge in the youth group where approx. 10% were not able to endorse the three preventive practices. This is a challenge for us and contributes to the gap between those who are infected and those who know their status. 57 HIV/AIDS KNOWLEDGE *Correct preventive practices is a Ministry of Health HIV/AIDS Program indicator which measures the proportion of the population able to endorse correct HIV/AIDS preventive practices. The younger age cohort (15-24 year olds) must endorse 3 preventive practices: condom use always, one faithful partner, abstinence while the older age cohort (25-49 year olds) must endorse 2 preventive practices: condom use always, one faithful partner Hope Enterprises Ltd.; June 2008; 2008 KABP Survey Findings Presentation 58 Jamaica’s Response to Treatment Care and Support for PLHIV 59 Major pillars of our response Increased access to Anti-Retroviral drugs (ARVs) prevent mother-to-child transmission (pMTCT) programme testing access for all infected persons living with HIV Health system strengthening An integrated programme with treatment, care, and support and prevention Community involvement and empowerment Strengthening Leadership 60 Major pillars of our response (cont.) Improving health infrastructure including laboratory capacity and laboratory information system Capacity building Strengthened monitoring and evaluation Building Partnerships and creating a supportive environment Communications 61 ARV Access Pro poor health policy Abolition of user fees providing universal access to all More than $1.2 B savings to the population ARV’s free Visits to health centres increased This has implications for early detection and for treatment, care and support. 62 Access to ARV’s Jamaica’s Treatment Programme started in 2003 with support from the Clinton Foundation and was later augmented by a Global Fund Grant of US$23 Million This provided the opportunity to establish a decentralised treatment programme seeing the establishment of 18 Treatment sites across the Island 63 Access to ARV’s Access to ARV’s scaled up through our network of Primary health care facilities model) Improvement in quality of care – reducing the waiting time at health facilities, the quality and ambience of the workplace, using patient flow analysis and space planning. Contact Investigators, and Community Peer Educators provide the community support. Voluntary, testing and counselling at treatment sites. Collaboration with supportive partners e.g. NGO’s, other agencies 64 Jamaica Annual AIDS Case Rates by Sex (Per 100,000 population): 1982 - 2007 Male Female 60 Rate per 100,000 pop. 50 40 30 20 10 0 Male Female '82 '83 0.09 0.09 0 0 '84 0 0 '85 '86 '87 '88 '89 '90 '91 '92 0.26 0.6 1.69 2.2 3.85 3.8 6.39 7.7 0 0 '93 '94 '95 '96 '97 '98 '99 '00 '01 '02 '03 '04 '05 '06 '07 11 16.1 25.7 24.2 29.1 31.9 41.7 41.7 39.6 44.5 46.9 46.3 53.3 50 33.6 1.28 0.85 1.6 1.99 5.35 3.26 6.62 11 15.2 14.6 18.6 18.2 27.5 31.6 33 31.3 34.3 38 48.2 38.8 25 65 Jamaica AIDS Cases & Deaths Reported Annually in Jamaica (1982 to 2007) 1600 Cases Deaths Number of Cases 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 '82 '83 '84 '85 '86 '87 '88 '89 '90 '91 '92 '93 '94 '95 '96 '97 '98 '99 '00 '01 '02 '03 '04 '05 '06 '07 Cases 1 1 0 3 7 35 36 65 70 143 135 219 335 511 491 609 643 892 903 939 989 1070 1112 1344 1186 1104 Deaths 0 1 1 0 9 18 21 40 37 105 108 146 200 269 243 393 375 549 617 588 692 650 665 514 432 320 66 Estimation of HIV MTCT Rate with Maternal HAART in Jamaica Jamaica: > 85% receive maternal HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy); > 90% infants receive ARV’s During Jan 2006 – Dec 2007, (2 years), estimated MTCT rate was 4.75% (with 19 of 400 PCR’s positive) [Polymerase Chain Reaction test] West Indian Medical Journal, March 2008 67 Challenges & Factors Driving the Epidemic 68 Factors Driving the Epidemic Early initiation of sexual activity Limited life-skills and sex education Insufficient condom use Multiple sex partners Stigma and Discrimination Commercial and transactional sex Substance abuse: crack/cocaine, alcohol Men having sex with men & homophobia Gender inequity and gender roles 69 Jamaica’s Response The Way Forward to universal Access Highly Active HIV Prevention 70 Strategic Way Forward 2007-2012 71 Goal Universal access to Prevention, treatment care and support services 72 Behavioral Change TREATMENT/ ARV/STI/ ANTIVIRAL Highly Active HIV Prevention Biomedical Strategies Social Justice and Human Rights Community involvement Leadership & scaling up of treatment/prevention efforts Combination Prevention STI = sexually transmitted infections 73 Strategic Areas 2007-2012 Prevention Building Capacity for HIV prevention in all sectors Structured targeted interventions among vulnerable populations - MSM, CSW & IEW* Comprehensive HIV/AIDS response in the Education sector Treatment Care and Support Enabling Environment and Human Rights Amendment of the Public Health Act Anti-discrimination Legislation Stigma reduction activities * men who have sex with men (MSM), commercial sex workers (CSW), intimate entertainment workers (IEW) 74 Strategic areas Empowerment and Governance Strengthened capacity and commitment of the Health Sector Strengthened capacity of other key sectors Three ones (M&E, Strategic plan, One Authority) Effective Procurement Monitoring and Evaluation Comprehensive and standard data collection tools Routine availability and utilization of reports for programme planning 75 Policy Advocacy for Supportive Policy and Legislative Framework to Facilitate interventions among key populations MSM, CSW, Youth, Young Men, the Homeless, Drug users, PLHIV etc. 76 The face of AIDS in Jamaica 77 "Investment in AIDS will be repaid a thousand-fold in lives saved and communities held together.” - Dr. Peter Piot, Past Executive Director, UNAIDS 78