The Economics of Baseball

advertisement

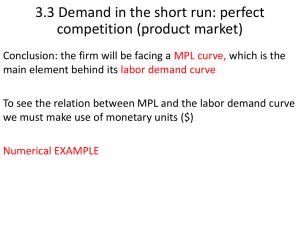

Player salaries, MRPL, and exploitation (revised 13 Nov. 2008) News flash: MLB players are highly paid • Average MLB salary = $3.2 M (April 2008) – More than 2 times as high as in 1998 – More than 10 times as high as in 1983 – Less than NBA ($5.4 M in 2007) – More than NHL (~$2 M in 2007) and NFL ($1.4 M in 2006) • Median MLB salary = $1 M in 2006, 2007, and 2008 – Highest ever; previous peak was $975,000 in 2000 – 85 players made $10 M or more in 2008 • Up from 66 in 2007 marginal revenue product of labor (MRPL) • = the amount of revenue that an employee generates for his employer • standard economic answer to “How much is that employee worth?” • can be measured in yearly terms (salary), or in hourly terms (hourly wage) • marginal product of labor (MPL) = how much OUTPUT an employee produces MRP theory & player pay • First, note that athletes are not the only very highlypaid people in U.S. society • Also, free-agent contracts are examples of VOLUNTARY EXCHANGE (market transactions agreed upon by buyer and seller) – Nobody forces the owners to pay such high salaries. • Rodney Fort: “talent is hired to produce [wins] in the long run.” – perhaps more than just wins... – Mark McGwire, 1998: extra MRPL of $15M? A labor market under perfect competition: Assumptions • Many buyers, many sellers – > nobody has market power • No restrictions on pay or employment • No cartels among employers or workers • Diminishing returns --> downward-sloping demand curve for labor • Upward-sloping supply curve for labor Notation (for diagram drawn on board): • • • • • L = # of workers ( = QL = quantity of labor) w = wage ( = PL = price of labor) SL = supply of labor DL = demand for labor MRPL = marginal revenue product of labor – MRPL = the amount of revenue that an additional worker generates for the firm Economic exploitation • MONOPSONY: a labor market with just one buyer • ECONOMIC EXPLOITATION • = difference between a worker’s marginal revenue product and his wage • = MRPL - w • In a monopsonistic labor market: • w < MRPL • w < w* (competitive wage) When the baseball players’ labor market was a monopsony • Until 1976, when all players were under the reserve clause. • RESERVE CLAUSE: a provision in baseball’s rules that allowed owners to renew a player’s contract automatically for one year. – Players either re-signed with their teams after each season or retired (or were traded or released). – No free agency; no competitive bidding for players. – Held salaries down; average salary = $25,000 in 1969. Independence Day • July 1976: new Basic Agreement gives all players free agency after 6 years of service. – Salaries surged after 1976; up 42% in 1976-77 – Can use monopsony diagram to illustrate • [See link on course website, “MLB’s Labor Economic History, 1945 Present,” for details on the Messersmith-McNally case that ended the reserve clause and brought free agency to MLB.] Baseball’s current system Years of ML Eligible for… service 0–2 Rookie minimum (Team can pay more if ($400,000 in 2009) it wants.) 3–5 Salary arbitration 6 or more Free agency (A handful of “Super Twos” also can go to arbitration.) Baseball’s salary explosion, 1976-present • “Freedom and prosperity” • Shift from monopsony to competitive bidding was less sudden than it seems – Over time, more and more teams played the FA market – Collusion against FA’s held salaries down in mid-1980s • Salary arbitration (1973-) allowed 3rd-to-6th-year players to piggyback on FA salary scale • MLB revenues surged -- attendance rose, TV revenues soared, stadium revenues soared, ... Comparison of performance (MRPL) and salaries • First, how to measure MRPL for baseball players? The standard, simplified way is a two-step process: – (1) Using player statistics, estimate each player’s contribution to team wins; – (2) Estimate the contribution of more wins to team revenues. For hitters, the one statistic that has the highest correlation with team winning percentages is... “OPS” • = On-base percentage (OBP) + Slugging percentage (SLG) • OPS * (player’s plate appearances as % of team’s) = what Zimbalist and Bradbury use to measure hitters’ productivity, in computing MRPL’s For pitchers • Earned run average (ERA) is the standard measure – Bradbury prefers “Defense-Independent Pitching Statistics” (DIPS), which is like ERA minus the contributions of the team’s fielders • Includes walks, strikeouts, and home runs allowed – Then compare a pitcher’s DIPS with the league average, and multiply by his innings pitched as a % of his team’s total. Next steps toward estimating MRPL • Estimate the player’s contribution to team winning percentage, based on wins as a function of OPS or ERA/DIPS • Estimate contribution of additional wins to team revenues Comparison of performance (MRPL) and salaries: • Exploitation = MRPL – salary • Zimbalist (1992): – Younger players tend to be exploited (pay<MRPL) – Veteran players (6+ years in majors) tend to be “overpaid” (pay>MRPL) • MRPL calculations by Bill Felber (The Book on the Book, 2005) echo Zimbalist’s conclusion. • MRPL calculations by Bradbury (p. 195) find pay<MRPL (i.e., “exploitation”) but a much smaller gap for veterans. – But Bradbury doesn’t “think this is exploitive” if you take development costs into account. MRPL - salary, by service category Salary as percentage of MRPL (2005, Bradbury; (1986-89, hitters, Zimbalist) pitchers) Years of service Category 0–2 reserved 16 – 25% (highly exploited) 11%, 10% 3–5 arbitrationeligible 50 – 64% (exploited) 23%, 22% 6 or more free-agenteligible 140% (overpaid) 92%, 64% How do we explain those systematically “overpaid”* veterans? • (* overpaid by Zimbalist’s and Felber’s estimates, not Bradbury’s) • Nature of the (seniority) system – Most free agents are past their prime (age 30+), which reduces their MRPL, but as free agents they’re in a position to earn the most money – Limited supply of free agent players – Many free-agent contracts are long term (less risky for player) • --> Reduced incentive to work hard? • Statistical MRPL measure (based on stats and wins) may be too narrow – Doesn’t count leadership, experience, consistency, marquee value – Also doesn’t count expected value of playoff or World Series success, or of extra offseason ticket sales due to a free-agent signing. • Back to supply and demand – Limited supply of free agents, high demand for players who can help a team – Concept of value above replacement – A player’s value is not just relative to the rest of the league, but also to his team’s next best option. • Ex.: A team that has no MLB-caliber catcher in its organization may be rational to “overpay” for a catcher. Salary arbitration • A mechanism for players with 3 to 5 years of service to avoid being underpaid relative to their peers • Established in 1973, implemented in 1974 • How it works: – If a player and his team cannot agree on his salary for the next season, then, separately: • The player submits a salary figure • The team submits a salary figure • An arbitrator decides which figure is more reasonable and awards it. – “Final offer” arbitration: The arbitrator must pick one figure or the other, cannot split the difference. – The player and team, however, can always settle on a compromise figure before the arbitration hearing. – The vast majority of arbitration-eligible players reach an agreement with their team before filing for arbitration or going to arbitration. » Salary arbitration is an acrimonious, risky process that players and teams generally seek to avoid. Effects of salary arbitration system • Higher salaries (for players with 3-5 years of MLB service) – “I was going to be rich or richer” – Salary arbitration and free agency a potent combination – Ironically, this is true even though owners have won the majority of salary arbitration cases. • More multi-year contracts for young players – Multi-year contracts are a way to avoid arbitration and yearly salary spiral.