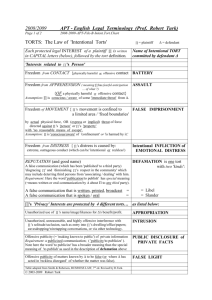

Torts Introduction to the Law of Torts Definitions of Tort Law Torts as

advertisement