articles on the chicano movement

advertisement

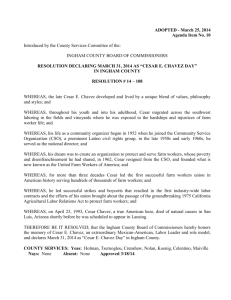

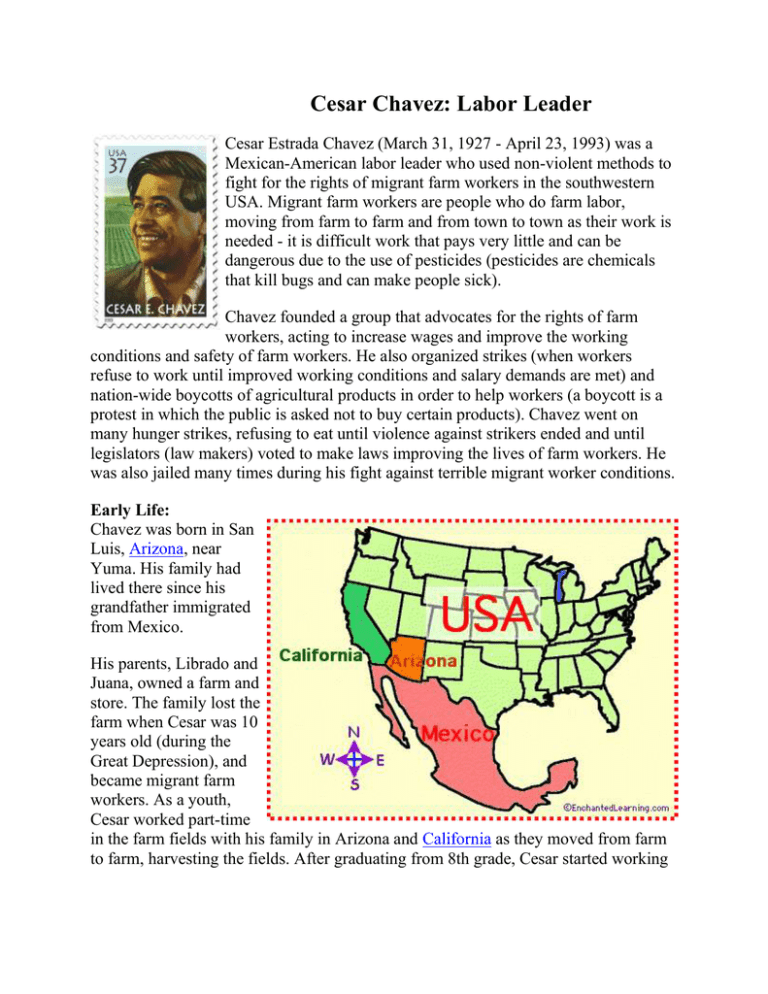

Cesar Chavez: Labor Leader Cesar Estrada Chavez (March 31, 1927 - April 23, 1993) was a Mexican-American labor leader who used non-violent methods to fight for the rights of migrant farm workers in the southwestern USA. Migrant farm workers are people who do farm labor, moving from farm to farm and from town to town as their work is needed - it is difficult work that pays very little and can be dangerous due to the use of pesticides (pesticides are chemicals that kill bugs and can make people sick). Chavez founded a group that advocates for the rights of farm workers, acting to increase wages and improve the working conditions and safety of farm workers. He also organized strikes (when workers refuse to work until improved working conditions and salary demands are met) and nation-wide boycotts of agricultural products in order to help workers (a boycott is a protest in which the public is asked not to buy certain products). Chavez went on many hunger strikes, refusing to eat until violence against strikers ended and until legislators (law makers) voted to make laws improving the lives of farm workers. He was also jailed many times during his fight against terrible migrant worker conditions. Early Life: Chavez was born in San Luis, Arizona, near Yuma. His family had lived there since his grandfather immigrated from Mexico. His parents, Librado and Juana, owned a farm and store. The family lost the farm when Cesar was 10 years old (during the Great Depression), and became migrant farm workers. As a youth, Cesar worked part-time in the farm fields with his family in Arizona and California as they moved from farm to farm, harvesting the fields. After graduating from 8th grade, Cesar started working full-time in the fields to help support his family (this was necessary because his father, Librado, had been injured in a car accident). Cesar served in the US Navy during World War 2. When Cesar Chavez returned from the war, he labored as a farm worker in California. Chavez married Helen Fabela in 1948; they eventually had 8 children and 31 grandchildren. Early Social Activism - Sí, Se Puede (Yes, it can be done): Chavez and his wife taught Mexican immigrants to read and organized voting registration drives for new US citizens. Chavez was greatly influenced by the peaceful philosophy of St. Francis of Assisi and Mohandas Gandhi. He joined the Community Service Organization, an organization that worked for the rights of farm workers. Starting a Union, Organizing Strikes and Boycotts - La Huelga (The Strike): In 1962, Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta and Gilbert Padilla started a union (a workers' rights group), called the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), to fight for "La Causa" (Spanish for "The Cause"). The NFWA organized "huelgas" (the Spanish word for "strikes"). There were many bitter and violent fights between the grape growers and the workers; Chavez and many union people were jailed in the struggle. Some agreements were eventually made between the farm workers union and the growers. In order to force growers to further improve farm worker conditions, Chavez organized a nation-wide lettuce boycott. In 1968, Chavez organized a five-year "grape boycott," a movement that urged people to stop buying California grapes until farm workers had contracts insuring better pay and safer working conditions. The name of the union was changed to the United Farm Workers (the UFW) in 1974. In 1978, when some of the workers' demands were met, the boycotts of lettuce and grapes were lifted. A Lifetime Quest for Social Justice - Viva La Causa (Long Live The Cause): Chavez's motto was "Si, se puede." (meaning "Yes, it can be done.") and he proved it to be true. His work for the fair treatment of farm workers changed the lives of millions of people for the better. After a lifetime of valiantly working for social justice, Chavez died of natural causes at the age of 66 (in 1993). In 1994, Chavez was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously (after his death). To this day, the UFW and Chavez's children and grandchildren continue his fight for social justice. The folowing essay will appear in the Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States, scheduled for publication in 2004. It is reprinted here with their kind permission. CESAR CHAVEZ By Rick Tejada-Flores Cesario Estrada Chavez, the most important Latino leader in U.S. history, was born in Yuma, Arizona on March 31, 1927 to Librado Chavez and Juana Chavez. He was the second of 5 children. The Chavez family had a small farm, and ran a country store. As the Depression intensified and years of drought forced thousands off the land, the Chavez family lost both their farm and store in 1937. Cesar was 10 years old when the family packed up and headed for California. These were difficult years, sleeping by the side of the road, moving from farm to farm, from harvest to harvest. Cesar would attend 38 different schools until he finally gave up after finishing the 8th grade. As Cesar learned the hard lessons of life, he absorbed important values from his parents. His father Librado taught him the value of hard work and opened his eyes to the inequities of the farm labor system. His mother Juana, a deeply religious and compassionate woman, emphasized the importance of caring for the less fortunate, and the power of love. In the early 1940s the Chavez family settled in Delano, a small farm town in the California’s San Joaquin valley, where Cesar would spend his teenage years. In 1946, 17 year-old Cesar Chavez enlisted in the Navy, spending what he would later describe as “the two worst years of my life.” When he got out of the service, he returned to Delano and married his high school sweetheart, Helen Favela. Their relationship, and the support that Helen would give him throughout his life, provided Chavez with the solid base that allowed him to devote his life to helping others. Cesar Chavez. Photo Credit: Rick Tejada-Flores Cesar and older Sister Rita at First Communion. Cesar and Helen moved to San Jose, where their first child Fernando was born. Over the years the family would grow to include 7 children – Fernando, Linda, Paul, Eloise, Sylvia and Anthony. In San Jose Chavez met a local priest, Father Donald McDonnell, who introduced him to the writings of St. Francis and Mahatma Gandhi, and the idea that nonviolence could be an active force for positive change. But he still needed to learn how to put these principles into action. The man who would teach Cesar Chavez how to put theory into practice arrived in San Jose in 1953. Fred Ross was an organizer. He was in San Jose to recruit members for the Community Service Organization. CSO helped its members with immigration and tax problems, and taught them how to organize to deal with problems like police violence and discrimination. To Chavez, Ross’ simple rules for organizing were nothing short of revolutionary. It was the beginning of a life-long friendship between Chavez and Ross. Teenage Cesar, a friend and brother Richard sport zoot zuit fashions. Chavez rapidly developed as an organizer, rising to become the president of CSO. When the organization turned down his request to organize farmworkers in 1962, he resigned and returned to Delano. From 1962 to 1965 he crisscrossed the state, talking to farmworkers. His new organization, the National Farmworkers Association (NFWA), would use the model of community service that Cesar had learned in CSO. Chavez didn’t want to call it a union, because of the long history of failed attempts to create agricultural unions, and the bitter memories of those who had been promised justice and then abandoned. In 1965, the union issue finally exploded. The Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), a mostly Filipino union, struck when the Delano grape growers cut the pay rates during the harvest. Chavez asked his organization to join the strike, and quickly became its leader. The strikers faced odds that could not be overcome by traditional labor tactics. Under Chavez’ leadership, the struggle became defined in new terms. They would Cesar in WWII Navy dress uniform. do battle non-violently, since they could never match the growers in physical force. They were a poor movement, so they would emphasize their poverty. For many years every organizer and volunteer from Chavez down would be paid room and board and $5 a week. Although there were picket lines in the fields, the real focus moved to the cities where grapes were sold. Hundreds of students, religious workers and labor activists talked to consumers in front of markets, asking them to do a simple thing: “Help the farmworkers by not buying grapes.” At its height, over 13 million Americans supported the Delano grape boycott. The pressure was irresistable, and in 1969 the Delano growers signed historic contracts with the United Farmworkers Organizing Committee, which would later become the United Farmworkers Union (UFW). Chavez had inspired an organization that did not look like a labor union. His vision didn’t include just the traditional bread and butter issues of unionism; it was about reclaiming dignity for people who were marginalized by society. What had started as the Delano grape strike came to be known as La Causa, the Cause. Whether they were farmworkers fighting for a better life, or middle class students trying to change the world, those who were drawn to the farmworkers movement were inspired by Chavez’ example to put aside their normal lives and make exceptional sacrifices. Chavez placed harsher demands on himself than on anyone else in the movement. In 1968 he fasted (the first of several fasts over his lifetime), to recommit the movement to non-violence. In many ways the fast epitomized Chavez’s approach to social change. On one level it represented his spiritual values, his willingness to sacrifice and do penance. At the same time, he and his lieutenants were extremely aware of the political ramifications of his actions, using the fast as a way of both publicizing and organizing for their movement. Fasting was just one expression of his deep spirituality. Like most farmworkers, Chavez was a devout Catholic. His vision of religion was a progressive one, that prefigured the “preferential option for the poor” of liberation theology. In the UFW, the mass was a call to action as well as a rededication of the spirit. The 1968 fast marked the beginning of Chavez’ emergence on the national political scene. Presidential candidate Robert Kennedy came to Delano to break bread with Cesar at the end of his fast. Chavez responded by committing UFWOC to campaign for Kennedy in the California primary. Their voter registration and get out the vote efforts provided Kennedy’s margin of victory in California. Over the years the UFW would become a significant political force, demonstrating that Mexican Americans could and would participate in electoral politics when their concerns were at stake. Chavez’ understanding of the relationship between economic issues and political participation was the starting point for a growing wave of Latino activism and electoral activity, that would eventually lead to the election of thousands of Latino officials and a major shift in the American political landscape. Chavez had never expected that victory in the battle for farmworkers’ rights would be achieved during his lifetime. In fact, the first stunning victories in the grapes were followed by major setbacks. First in the lettuce industry, and then when the grape contracts expired in 1972, growers sought out the powerful Teamsters Union, and signed contracts with them that rolled back the UFW's hard fought gains. The UFW responded with strikes that led to the jailing of thousands. Many strikers were injured by violent attacks on the picket lines, and two were killed in dreveby shootings and attacks.. But the “inter-union” battle had left the public confused and made a new boycott against lettuce and grape growers difficult. Chavez looked for a political solution to the impasse. He supported Jerry Brown’s bid to become governor of California, and in return was able to engineer the nation’s first law giving farmworkers the right to union elections. The passage of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act in 1975 led to an overwhelming series of UFW election victories, and it seemed that Chavez had finally achieved his goal of organizing farmworkers. Cesar plays softball with his teenage son Paul. Helen and Cesar Chaves in the 1960's with 3 of their children. The UFW had given up the boycott in exchange for the right to union elections. But relying on the law became uncertain, as growers learned to use it to delay signing contracts. After early successes under the farm labor law, Chavez pulled back from organizing, although he continued to travel extensively to promote awareness of the farmworkers struggle. The election of a Republican governor in 1982 made enforcing the law even more difficult. Chavez’ goals and vision were changing as well. He began to focus on the dangers of pesticides, which had always been a major source of illness among A weary Cezar Chavez during a rare moment of solitude. farmworkers. It was a subject that drew a positive response from an environmentally conscious public. Instead of using volunteers, he relied more and more on direct mail. He built low-cost housing for farmworkers, and considered starting an urban organizing campaign in Mexican-American communities. He became interested in modern management techniques and group dynamics, including the group therapy techniques of Synanon, a drug rehabilitation program. Although questions were raised about his effectiveness in later years, Cesar Chavez had become a remarkable symbol — for Latinos, community activists, the labor movement, young people, and all who valued his values and commitment. He had accomplished something that no one else had ever been able to do; build a union for farmworkers. In the process he trained a generation of activists who would apply their skills in other communities and struggles. Cesar Chavez died in Yuma Arizona on April 23, 1993, near his birthplace in Yuma, Arizon. He was 66 years old. His funeral in Delano attracted thousands of Americans from all walks of life. Years before his death, Chavez was asked by a union member if he wanted to be remembered by statues and public memorials. Chavez replied, “If you want to remember me, organize!” The Chicano Movement emerged during the Civil Rights era with three goals: restoral of land, rights for farm workers and education reforms. Prior to the 1960s, however, Latinos lacked influence in the national political arena. That changed when the Mexican American Political Association worked to elect John F. Kennedy president in 1960, establishing Latinos as a significant voting bloc. After Kennedy was sworn into office, he showed his gratitude toward the Latino community by not only appointing Hispanics to posts in his administration but also by considering the concerns of the Hispanic community. As a viable political entity, Latinos, particularly Mexican Americans, began demanding that reforms be made in labor, education and other sectors to meet their needs. A Movement with Historic Ties When did the Hispanic community’s quest for justice begin? Their activism actually predates the 1960s. In the 1940s and ’50s, for example, Hispanics won two major legal victories. The first—Mendez v. Westminster Supreme Court—was a 1947 case that prohibited segregating Latino schoolchildren from white children. It proved to be an important predecessor to Brown v. Board of Education, in which the U.S. Supreme Court determined that a “separate but equal” policy in schools violated the Constitution. In 1954, the same year Brown appeared before the Supreme Court, Hispanics achieved another legal feat in Hernandez v. Texas. In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed equal protection to all racial groups, not just blacks and whites. In the 1960s and '70s, Hispanics not only pressed for equal rights, they began to question the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This 1848 agreement ended the Mexican-American War and resulted in America acquiring territory from Mexico that currently comprises the Southwestern U. S. During the Civil Rights Era, Chicano radicals began to demand that the land be given to Mexican Americans, as they believed it constituted their ancestral homeland, also known as Aztlán. In 1966, Reies López Tijerina led a three-day march from Albuquerque, N.M., to the state capital of Santa Fe, where he gave the governor a petition calling for the investigation of Mexican land grants. He argued the U.S.’s annexing of Mexican land in the 1800s was illegal. Activist Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, known for the poem “Yo Soy Joaquín,” or “I Am Joaquín,” also backed a separate Mexican-American state. The epic poem about Chicano history and identity includes the following lines: “The Treaty of Hidalgo has been broken and is but another treacherous promise. / My land is lost and stolen. / My culture has been raped.” Farm Workers Make Headlines Arguably the most well-known fight Mexican Americans waged during the 1960s was that to secure unionization for farm workers. To sway grape growers to recognize United Farm Workers--the Delano, Calif., union launched by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta--a national boycott on grapes began in 1965. Grape pickers went on strike, and Chavez went on a 25-day hunger strike in 1968. At the height of their fight, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy visited the farm workers to show his support. It took until 1970 for the farm workers to triumph. That year, grape growers signed agreements acknowledging UFW as a union. Philosophy of a Movement Students played a central role in the Chicano fight for justice. Notable student groups include United Mexican American Students and Mexican American Youth Association. Members of such groups staged walkouts from schools in Denver and Los Angeles in 1968 to protest Eurocentric curriculums, high dropout rates among Chicano students, a ban on speaking Spanish and related issues. By the next decade, both the Department of Health, Education and Welfare and the U.S. Supreme Court declared it unlawful to keep students who couldn’t speak English from getting an education. Later, Congress passed the Equal Opportunity Act of 1974, which resulted in the implementation of more bilingual education programs in public schools. Not only did Chicano activism in 1968 lead to educational reforms, it also saw the birth of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, which formed with the goal of protecting the civil rights of Hispanics. It was the first organization dedicated to such a cause. The following year, hundreds of Chicano activists gathered for the First National Chicano Conference in Denver. The name of the conference is significant as it marks the term “Chicano's” replacement of "Mexican." At the conference, activists developed a manifesto of sorts called “El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán,” or “The Spiritual Plan of Aztlán.” It states, “We…conclude that social, economic, cultural, and political independence is the only road to total liberation from oppression, exploitation, and racism. Our struggle then must be for the control of our barrios, campos, pueblos, lands, our economy, our culture, and our political life.” The idea of a unified Chicano people also played out when political party La Raza Unida, or the United Race, formed to bring issues of importance to Hispanics to the forefront of national politics. Other activist groups of note include the Brown Berets and the Young Lords, which was made up of Puerto Ricans in Chicago and New York. Both groups mirrored the Black Panthers in militancy. Looking Forward Now the largest racial minority in the U.S., there’s no denying the influence that Latinos have as a voting bloc. While Hispanics have more political power than they did during the Civil Rights Era, they also have new challenges. Immigration and education reforms are of key importance to the community. Due to the urgency of such issues, this generation of Chicanos will likely produce some notable activists of its own.