dbq on minorities

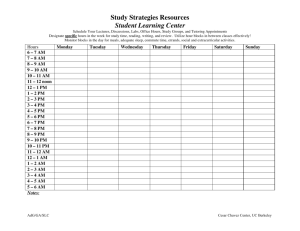

advertisement

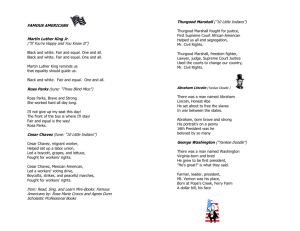

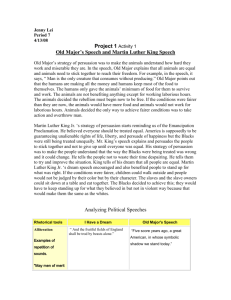

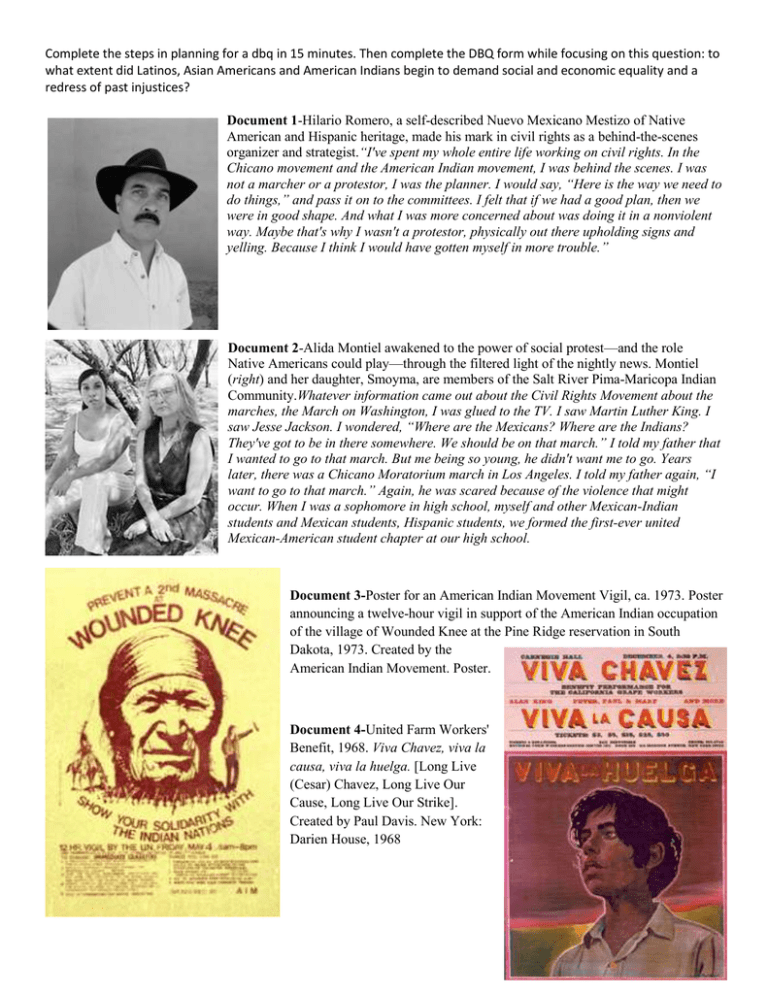

Complete the steps in planning for a dbq in 15 minutes. Then complete the DBQ form while focusing on this question: to what extent did Latinos, Asian Americans and American Indians begin to demand social and economic equality and a redress of past injustices? Document 1-Hilario Romero, a self-described Nuevo Mexicano Mestizo of Native American and Hispanic heritage, made his mark in civil rights as a behind-the-scenes organizer and strategist.“I've spent my whole entire life working on civil rights. In the Chicano movement and the American Indian movement, I was behind the scenes. I was not a marcher or a protestor, I was the planner. I would say, “Here is the way we need to do things,” and pass it on to the committees. I felt that if we had a good plan, then we were in good shape. And what I was more concerned about was doing it in a nonviolent way. Maybe that's why I wasn't a protestor, physically out there upholding signs and yelling. Because I think I would have gotten myself in more trouble.” Document 2-Alida Montiel awakened to the power of social protest—and the role Native Americans could play—through the filtered light of the nightly news. Montiel (right) and her daughter, Smoyma, are members of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community.Whatever information came out about the Civil Rights Movement about the marches, the March on Washington, I was glued to the TV. I saw Martin Luther King. I saw Jesse Jackson. I wondered, “Where are the Mexicans? Where are the Indians? They've got to be in there somewhere. We should be on that march.” I told my father that I wanted to go to that march. But me being so young, he didn't want me to go. Years later, there was a Chicano Moratorium march in Los Angeles. I told my father again, “I want to go to that march.” Again, he was scared because of the violence that might occur. When I was a sophomore in high school, myself and other Mexican-Indian students and Mexican students, Hispanic students, we formed the first-ever united Mexican-American student chapter at our high school. Document 3-Poster for an American Indian Movement Vigil, ca. 1973. Poster announcing a twelve-hour vigil in support of the American Indian occupation of the village of Wounded Knee at the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota, 1973. Created by the American Indian Movement. Poster. Document 4-United Farm Workers' Benefit, 1968. Viva Chavez, viva la causa, viva la huelga. [Long Live (Cesar) Chavez, Long Live Our Cause, Long Live Our Strike]. Created by Paul Davis. New York: Darien House, 1968 Complete the steps in planning for a dbq in 15 minutes. Then complete the DBQ form while focusing on this question: to what extent did Latinos, Asian Americans and American Indians begin to demand social and economic equality and a redress of past injustices? Document 5-Rodriguez, Arturo. The Story of Cesar Chavez, Web. 2014. In 1962 Cesar founded the National Farm Workers Association, later to become the United Farm Workers - the UFW. He was joined by Dolores Huerta and the union was born. For a long time in 1962, there were very few union dues paying members. By 1970 the UFW got grape growers to accept union contracts and had effectively organized most of that industry, at one point in time claiming 50,000 dues paying members. The reason was Cesar Chavez's tireless leadership and nonviolent tactics that included the Delano grape strike, his fasts that focused national attention on farm workers problems, and the 340-mile march from Delano to Sacramento in 1966. The farm workers and supporters carried banners with the black eagle with HUELGA (strike) and VIVA LA CAUSA (Long live our cause). The marchers wanted the state government to pass laws which would permit farm workers to organize into a union and allow collective bargaining agreements. Cesar made people aware of the struggles of farm workers for better pay and safer working conditions. He succeeded through nonviolent tactics (boycotts, pickets, and strikes). Cesar Chavez and the union sought recognition of the importance and dignity of all farm workers. Document 6-Irigone, Frank. Kingdome Protest and HUD March, 1972. Web. 2015. The groundbreaking for Seattle's Kingdome on November 2, 1972 was supposed to be a public celebration. But Asian American youth, upset that the stadium was located immediately next to Seattle's International District (ID), disrupted the event and brought media attention to concerns that had largely been ignored. Activists worried that the people attending Kingdome events would soon overwhelm Seattle's historically Asian American neighborhood with their parking and commerical needs. A lawsuit filed by Peter Bacho on behalf of Asian elderly in the neighborhood (including famous union leader Chris Mensalvas) failed to force King County to build the stadium elsewhere. Asian American youth, who had chosen to stay out of the Kingome issue until the lawsuit was resolved, decided it was time to take action. An impromptu march from the Asian drop-in center to the Kingdome's groundbreaking arrived as the event's dignataries were taking the stage. Activists shouted down speakers, threw mud balls at the stage, got in a heated exchange with City Council President Liem Tuai (who they considered a sellout), and were eventually chased off by angry Seattle police. Though the protesters did not issue demands as much as they expressed their anger, the media coverage they generated challenged stereotypes about passive Asians and gave a greater sense of urgency to neighborhood meetings. Document 7-Asian Family Affair. Vol. 1, No. 3, April, 1972. Pamphlet printed concerning Kingdome building.