AP English Literature & Composition Rhetorical Terms Syntax

advertisement

AP English Literature & Composition Rhetorical Terms Syntax, Poetry, and Sound Ms. Storm As AP Lit. students, I expect that you already know the meanings of: • • • • • • • • • • • • • Metaphor Simile Figurative language Allusion Hyperbole Analogy Oxymoron Paradox Personification Symbol Understatement Diction: denotation, connotation Conflict • • • • • • • • • • • Imagery Foreshadowing Mood Plot Point of view Setting Tone Theme Characterization Protagonist Antagonist These are the basics that we will build on to achieve deeper, more analytical readings of texts. This PPT • This PPT explains terms that you may not have known coming into AP Literature. • After looking at these, you are responsible for identifying them when present and being able to analyze how they contribute to the meaning of the text. Sentence structure SYNTAX Syntax • Syntax simply means “sentence structure.” – Authors oftentimes use sentence structure to create meaning by emphasizing certain ideas, mirroring the idea of the sentence, or even using punctuation in a certain way. Syntax • There are many ways to analyze syntax, including: – – – – – – Function/purpose Length Arrangement of ideas Repetition Punctuation etc. Function/Purpose • Declarative: makes a statement – It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife. • Interrogative: asks a question (?) – "Do you not want to know who has taken it?" cried his wife impatiently. • Exclamatory: exclaims something (!) – "Oh! Single, my dear, to be sure!” • Imperative: makes a command – “go and see Mr. Bingley when he comes into the neighbourhood.” Length • Telegraphic sentence: a very short sentence, usually of five or less words – “Call me Ishmael.” – Often used for emphasis, to create a terse or annoyed tone, to quicken the pace. Length • Long: … a long sentence. – “For a moment the boy thought too that the man meant his older brother until Harris said, ‘Not him. The little one. The boy,’ and, crouching, small for his age, small and wiry like his father, in patched and faded jeans even too small for him, with straight, uncombed, brown hair and eyes gray and wild as storm scud, he saw the men between himself and the table part and become a lane of grim faces, at the end of which he saw the justice, a shabby, collarless, graying man in spectacles, beckoning him.” – Often used to indicate stream of consciousness, confusion, rapid thought, multiplicity/extensiveness of ideas Arrangement of Ideas • Cumulative sentence: a sentence that begins with the main idea and then expands upon it in later clauses. – “I write this at a wide desk in a pine shed as I always do these recent years, in this life I pray will last, while the summer sun closes the sky to Orion and to all the other winter stars over my roof.” • Periodic sentence: a sentence that ends with the main idea and expands upon it in previous clauses. – “With two raw blisters and now unable to carry my pack due to two broken ribs and broken collar bone, I stared at my dead phone pleadingly.” Arrangement of Ideas • Chiasmus: arrangement of repeated thoughts in an X Y Y X pattern – “Fair is foul, and foul is fair” Repetition • Anadiplosis: repetition of the last word of one clause at the beginning of the following clause – “Aboard my ship, excellent performance is standard. Standard performance is sub-standard. Substandard performance is not permitted to exist.” • Anaphora: repetition of initial clauses – “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness…” Repetition • Epistrophe: repetition of phrases at the ends of clauses (opposite of anaphora) – “We are born to sorrow, pass our time in sorrow, end our days in sorrow.” Other • Parallelism: Similarity of structure in a pair or series of related words, phrases, or clauses. – “King Alfred tried to make the law clear, precise, and equitable.” (all adjectives) • Fragment: an incomplete sentence (i.e. missing a subject, verb, or complete thought). – “A risk to own anything: a car, a pair of shoes, a packet of cigarettes. Not enough to go around, not enough cars, shoes, cigarettes. Too many people, too few things.” Other • Asyndenton: sentence that lists without conjunctions – “her daughters, alarmed, anxious, uneasy.” • Polysyndenton: sentence that lists using many conjunctions – “I said, ‘Who killed him’ and he said,’I don't know who killed him but he's dead all right’ and it was dark and there was water standing in the street and no lights and windows broke and boats…” The most intense, concentrated form of the human experience POETRY Meter • Meter: a regular pattern of syllables (unstressed and stressed) • Foot: metrical units that consist of some pattern of unstressed and stressed syllables Meter Feet Line Length Iambic (unstressed – stressed) One foot: monometer Trochaic (stressed – unstressed) Two feet: dimeter Anapestic (unstressed – unstressed – stressed) Three feet: trimeter Dactylic (stressed – unstressed – unstressed) Four feet: tetrameter Five feet: pentameter e.g. if you have an anapestic pattern that repeats four times in a line, you have anapestic tetrameter. You should absolutely know iambic for the AP test. Rhyme • End rhyme: last word of two different lines rhyme • Internal rhyme: rhyme within a single line – “To the rhyming and chiming of the bells!” • Slant rhyme: inexact end rhyme (e.g. “stone” and “gone”) Parts of Poems • Stanza: a “paragraph” within a poem; a grouping of lines often separated from others by a blank line • Shift: a rhetorical shift or dramatic change within a poem, usually at a stanza break (but not always) Types of Poems • Elegy: a poem that mourns the death of someone or something (e.g. “O Captain! My Captain” by Whitman, lamenting the death of Abraham Lincoln) • Epic: a long poem that narrates the events in a hero’s life (e.g. Homer’s The Odyssey) • Ode: a poem of praise, often written in an elevated style (e.g. “Ode to a Nightingale” by Keats) • Lyric: a songlike poem that contains strong personal emotions • Sonnet: a 14 line poem written in iambic pentameter [there are many types of sonnets, we will focus on the Shakespearean sonnet] Shakespearean Sonnet-Specific Terms • Quatrain: group of four lines • Volta: the “turn” (indicating a shift) between lines 8 and 9 • Heroic couplet: the final two lines; the “key” to the poem’s theme Quatrain 1 (lines 1-4) Quatrain 2 (lines 5-8) Volta Quatrain 3 (lines 9-12) Heroic couplet My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red than her lips' red; If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. I have seen roses damask'd, red and white, But no such roses see I in her cheeks; And in some perfumes is there more delight Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks. I love to hear her speak, yet well I know That music hath a far more pleasing sound; I grant I never saw a goddess go; My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground: And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare As any she belied with false compare. & Sense SOUND Sound • Alliteration: repetition of initial consonant sounds – “The weeping willow waves” • Assonance: the repetition of vowel sounds within two or more words of close proximity – “lake” and “fate” • Consonance: the repetition of consonant sounds within two or more words of close proximity – “Nick dropped the locket in the thick mud” Sound • Euphony: musical, pleasant sounds – “The Oars divide the Ocean, / Too silver for a seam” • Cacophony: harsh, discordant sounds – “My stick fingers click with a snicker” • Note: this is also an example of consonance. Sound • Onomatopoeia: sound words, like “boom,” “pop,” “hiss,” etc.

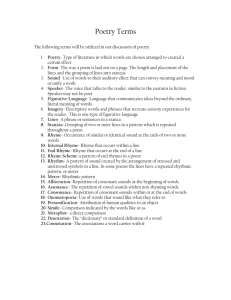

![English poetic terms[1].](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/009640365_1-09d91eea13bb5c84d21798e29d4b36a3-300x300.png)