NASP: New Orleans, 2008 Hank Fien, Ph.D. Rachell Katz, Ph.D

advertisement

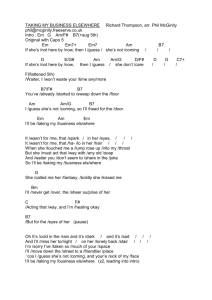

Does phonemic decoding skill predict reading proficiency for English Learners? NASP: New Orleans 2008 Hank Fien, Ph.D. Rachell Katz, Ph.D. Scott K. Baker, Ph.D. Jeanie Mercier Smith, Ph.D. oregonreadingfirst.uoregon.edu/ Acknowledgements Oregon Department of Education -- Reading First (Joni Gilles, Reading First Director) Oregon Reading First Center -- Center on Teaching and Learning, University of Oregon Pacific Institutes for Research Line of Research Assessment Purpose Study Example Screening Progress Outcomes *Concurrent and predictive validity (completed manuscript) Diagnostic accuracy (e.g., ROC curves, NPV, PPV) (manuscript in prep) form of growth (data analysis in prep) function of growth (ORF paper in press) Validating benchmark goals related to high stakes outcomes Performance in relation to validated treatments (heart of RTI concept) Since it cost a lot to win, but even more to lose You and I bound to spend some time wondering which to choose -R. Hunter, 1971 The Case for Prevention The central goal of Reading First, that all children reach grade level reading proficiency by the end of third grade, requires an integrated system of reading instruction and assessments designed to prevent reading problems. (P.L. 107-110, Part B, Subpart 1, 2002). Additionally, the Response to Intervention (RtI) initiative attempts to reduce the number of students who are misidentified as having a learning disability by intervening strategically and intensely in the early grades (P.L. 108-446, Part B, Sec 614 (b)(6)(b)). The basis of the prevention framework of these reforms is substantial evidence demonstrating the importance of early academic achievement on a range of long-term outcomes (Finn, Gerber, & Boyd-Zaharias, 2005). The Case for Universal Screening of Foundational Reading Skills The level of schoolwide assessment data needed for prevention-oriented reform is unprecedented in public education. These assessments must be able to provide a direct measure of an important skill that can approximate performance on a comprehensive measure of learning. In the early grades a foundational skill of later reading proficiency is the alphabetic principle, which is the ability to link the internal structure of words (letters and letter strings) to their sounds (phonemes). Unpacking the Alphabetic Principle The alphabetic principle is comprised of two fundamental skills: (a) alphabetic understanding—knowledge of lettersound correspondences, and (b) phonological recoding—the ability to blend sounds to read words (National Research Council, 1998). Thus, a critical component of an assessment system should include a direct measure of student’s alphabetic understanding and phonological recoding skill. Assessing the Alphabetic Principle using Pseudoword Reading There is strong empirical support for the use of measures of pseudoword reading to assess the alphabetic principle (Beech & Awaida, 1992; Felton & Wood, 1992; Manis et al., 1990) Numerous studies have reported strong correlations between the ability to read pseudowords and the ability to read real words (Beech & Awaida, 1992; Felton & Wood, 1992; Manis et al., 1990). In fact, Curtis (1980) concluded that the ability to read pseudowords was the single best predictor of reading ability. Word reading ability was found to be the key predictor of reading comprehension, and pseudoword reading regularly accounted for the greatest portion of variance in word reading performance. NWF a Measure of Alphabetic Principle Nonsense Word Fluency (NWF) is a direct measure of pseudoword reading designed to measure alphabetic understanding and phonological recoding ability (Good, Baker, & Peyton, in press). Measures such as NWF, and other pseudoword reading measures specifically isolate how well students apply their understanding of phonics rules in learning to decode. The measure expressly avoids tapping student skills in reading real words because it may not be clear what strategies the student is using to accurately read real words. Prior studies of NWF Three published studies have further examined the validity of NWF: In the first study, correlations between level estimates of NWF in the winter of first grade with ORF in the spring of first grade were .78, accounting for 61% of the variance on the ORF outcome measure (Good, Simmons, & Kame’enui, 2001). In a second study, researchers investigated the validity of three DIBELS subtests administered in kindergarten, including NWFin a large urban school district in Philadelphia (Rouse & Fantuzzo, 2006). Concurrent correlations in kindergarten were .62 with the Developmental Reading Assessment (DRA; Beaver, 1997) Instructional Reading score, .53 with the Test of Early Reading Ability (TERA-3; Reid, Hresko, & Hammill, 2001) Reading Quotient, and .56 with the TERA-3 Alphabet subtest. Predictive correlations with first grade outcomes were reported as .63 for the DRA Instructional Reading score, and .50 for the Terra Nova (CTB/McGraw-Hill, 1997) Reading subtest. Prior studies of NWF (cont.) In a more recent study, Riedel (2007) focused on the relative contribution of NWF in the middle and end of first grade when both ORF and NWF were administered. Predictive and concurrent correlation between NWF and the GR+DE a group-administered standardized test of overall reading ability (Williams, 2001) administered at end of first grade, were .45 and .46. Logistic regression analyses indicated that ORF accounted for the majority of the variance in the GR+DE. The NWF correlations were significantly lower than correlations reported in previous studies. Assessing the Alphabetic Principle in English with English Learners English learners are expected to be included in reading reform efforts such as Reading First and RTI These reforms require screening measures to identify problems in phonological awareness, alphabetic understanding, and reading fluency Need to investigate whether measures -- and purposes used -- function similarly for ELs and ESs Reading in English Example a b m the the cat sat on the mat. the bat sat on the cat. c t s o n What animal was on top? What animal was in the middle? What thing was on the bottom? Assessing the Alphabetic Principle in English with English Learners Measures of pseudoword appear to be associated with reading comprehension with ELs Lesaux and Siegel (2003) found that alphabetic principle in K was the best predictor of word reading and comprehension in Grade 2 Assessing the Alphabetic Principle in English with English Learners By contrast, oral proficiency in a second language is NOT strongly or moderately associated with word reading or simple text reading Implication is students might be able to decode but not have the language skills to read with meaning Assessing the Alphabetic Principle in English with English Learners Geva and Yaghoub Zadeh (2006) found that ELs in G2 read simple texts at or slightly below oral language proficiency level with the same efficiency as ESs oral proficiency in the second language contributed only marginally to efficiency of word reading or simple text reading When reading materials were more demanding (vocabulary and syntax), oral language proficiency played a stronger role in text comprehension Still, the role oral language played was small overall The alphabetic principle with English Learners Students with limited language proficiency read words without necessarily knowing their meaning (Bialystock, Luk, & Kwan, 2005) The bat, cat, sat example If native language is alphabetic (e.g., Spanish) reader may recognize letter sounds that are similar in English and Spanish (e.g., almost all consonants) without speaking English ELs may be able to perform well on pseudoword reading tasks without necessarily having the English language and vocabulary skills required for adequate reading comprehension. The alphabetic principle with English Learners Studies have shown that the best predictors of early reading in English for ELs are phonological awareness, print awareness, and alphabetic knowledge Chiappe, Siegel, & Wade-Wooley, 2002; Durgunoglu, Nagy, & Hancin-Bhatt, 1993; Lesaux & Siegel, 2003), And oral language proficiency does not predict how well children will learn phonological awareness and phonics Geva & Yaghoub Zadeh, 2006 Findings suggest association between pseudoword reading and other reading outcomes may be more complex for ELs than ESs Purpose of the Study Investigate facility with alphabetic principle by examining concurrent and predictive relations among measures in schools implementing Reading First. The possible use of NWF (Good & Kaminski, 2002) as a universal screening tool and as an index of beginning reading proficiency for all K-2 students. Investigate NWF with ELs Reading First schools typically use the same measures to assess ELs and ESs. Many of these measures have not been investigated empirically with ELs Research Questions 1. The strength of the association between NWF and criterion measures of reading for all K-2 students in participant schools 2. Differences in the magnitude of associations between NWF and criterion measures for ELs and ESs 3. Stability of NWF scores over time among ELs and ESs Method: Study Setting Oregon Reading First schools 77% free or reduced lunch rates, 27% third graders did not pass Oregon Statewide Reading Assessment 14 districts: urban, rural and mid-size cities Full time reading coach in each building Monthly grade level meetings to examine progress monitoring data Intense professional development for teachers and instructional staff Reading First Reading Instruction A comprehensive (core) instructional program adopted and implemented K-3 At least 90 minutes per day of uninterrupted beginning reading instruction Minimum of 30 minutes teacher directed small group instruction Based on student performance and resources In Grade 1, an instruction focus was development of phonics skills in Also instruction emphasized phonemic awareness, fluency, reading comprehension and vocabulary Method: Student Participants K English Learners (25%) n = 1370 English Speakers (75%) n = 5629 1 n = 1969 n = 4949 2 n = 1687 n = 4147 % in Special Education 7.4% 6.9% Measures Predictor NWF Criterion K (mid end) 1 (beg mid end) 2 (beg) SAT-10 K, 1, 2 (spring) ORF G1 and 2 (spring) Nonsense Word Fluency Student Copy kik kaj lan yuf bub wuv nif suv yaj tig woj fek nul pos dij nij vec yig zof mak sig av zem vok sij pik al dit um sog faj zin og viv vus nok boj tum vim wot yis zez nom feg tos mot nen joj vel sav Place the student copy of the probe in front of the child. Here are some more makebelieve words (point to the student probe). Start here (point to the first word) and go across the page (point across the page). When I say “begin,” read the words the best you can. Point to each letter and tell me the sound or read the whole word. Read the words the best you can. Put your finger on the first word. Ready, begin. Results Predictive and concurrent associations (correlations) between NWF and SAT-10 and NWF and ORF Stability coefficients on NWF Table 2. Concurrent and Predictive Correlations for NWF with ORF at End of 1st and 2nd Grade and SAT10 Scores at the End of Kindergarten, 1st, and 2nd Grade ORF SAT10 Winter K Spring K Fall 1st Winter 1st Spring 1st Fall 2nd Spring 1st r .65† .71 .74† .76 .76 - Spring 2nd r .51† .59 .61 .67 .69 .72 Spring K r .73† .73† - - - - Spring 1st r .63† .65 .65 .66 .65 - Spring 2nd r .56† .58 .57 .59 .56 .59 Note. See Table 3 for separate correlations, Ns, and statistically significant differences between ELs and ESs. †Correlations differ between EL and ES students by more than 5% overlapping variance. Table 3. Concurrent and Predictive Correlations for NWF with ORF and SAT10 Scores Shown Separately for English Learners (EL) and English Speakers (ES) ORF Spring 1st Spring 2nd Winter K Spring K Fall 1st Winter 1st Spring 1st Fall 2nd rel .57 .68 .70 .74 .75 - res .65 .71 .74 .76 .76 Nel 1112 1160 1951 2048 2147 Nes 2258 2319 4528 4859 5148 p .0004 .1390 .0009 .0224 .5146 rel .41 .56 .58 .65 .67 .71 res .54 .60 .60 .67 .69 .71 Nel 481 499 1134 1188 1214 1833 Nes 829 842 2151 2246 2299 4329 .0027 .3097 .3308 .2904 .2834 .6738 p Table 3. Concurrent and Predictive Correlations for NWF with ORF and SAT10 Scores Shown Separately for English Learners (EL) and English Speakers (ES) SAT10 Spring K Spring 1st nd Spring 2 Winter K Spring K Fall 1st Winter 1st rEL .64 .66 - - - - rES .73 .73 NEL 1288 1361 NES 5360 5595 p .0000 .0000 rEL .54 .63 .62 .65 .62 - rES .62 .63 .64 .66 .65 NEL 1067 1111 1827 1907 1960 NES 2240 2297 4387 4702 4885 p .0006 .9249 .1775 .4000 .0533 rEL .43 .53 .51 .55 .54 .58 rES .55 .56 .56 .58 .56 .59 NEL 469 485 1037 1086 1109 1655 NES 796 809 2029 2115 2167 4078 .0068 .4089 .1021 .2569 .4282 .6757 p Spring 1st Note. p-values represent the statistical test for the difference between correlations for ELs and ESs, using Fisher’s r-to-Z transformation. To correct for the number of comparisons, we recommend interpreting only p-values below .001 as statistically significant. Fall 2st Table 4. Intercorrelations Between NWF Scores Across Assessment Times for English Learners in the Lower Left and English Speakers in the Upper-Right Spring K Fall 1st Winter 1st Spring 1st Fall 2nd r .73* .68* .58* .50 .47 N 5567 2527 2361 2258 893 Winter K Winter K Spring K Fall 1st Winter 1st Spring 1st Fall 2nd r .64* .76 .70 .57 .56 N 1412 2601 2430 2319 908 r .60* .77 .73 .60 .58 N 1206 1258 4828 4530 2361 r .49* .68 .69 .73 .68 N 1141 1190 2012 4860 2482 r .40 .54 .55 .69 .75 N 1112 1160 1951 2048 2565 r .35 .47 .52 .65 .72 N 507 528 1201 1269 1306 *Correlations differ between EL and ES students (p < .001) Discussion First, the strength of the association between NWF and criterion measures of reading performance was investigated for all students assessed in Reading First schools. The performance of NWF in this study supports prior research demonstrating the validity of pseudoword reading measures and their association with criterion measures of reading proficiency (Curtis, 1980; Gough, Juel, & Griffith, 1992; Rouse & Fantuzzo, 2006). The validity coefficients found in this study largely replicate findings from earlier studies of NWF (Good et al., 2001; Good et al., 2002; Rouse & Fantuzzo, 2006). However, concurrent and predictive validity estimates from this study were significantly higher in first grade than correlations reported by Reidel (.63 to .66 compared to .45 to .46). We do not have a clear idea why these differences may have occurred but do note the studies differed in terms of criterion outcome measures and student populations. Discussion A second purpose of this study was to examine psychometrically how a measure of the alphabetic principle functions for an important group of students, ELs. To date, no study has examined the association between measures of the alphabetic principle and criterion measures of reading, such as ORF and the SAT-10, with ELs specifically. In general, the evidence appears strong that NWF reflects a similar measurement construct for ELs and ESs and can be used for similar purposes in schoolbased contexts. Discussion The third purpose of this study was to examine the stability of NWF for ELs and ESs. The stability correlations for NWF over time were highly comparable for these two groups. In summary, the NWF measure predicted an important portion of the variance on ORF and SAT-10 scores for all students involved in Reading First. Although there were important discrepancies in predictive and concurrent correlations with criterion measures between ELs and ESs, most of the correlations were highly similar, and indicate robust performance of NWF across groups. Implications for Practicing School Psychologists Although the legislative origins differ for Reading First (i.e., NCLB) and Response to Intervention (i.e., IDEA), the underlying features of each initiative are highly similar (Gersten & Dimino, 2006). Both initiatives emphasize that the best way to prevent or minimize reading problems is through early identification and strategic intervention. Both Reading First and Response to Intervention (RtI) emphasize schoolwide approaches to reading instruction and promote effective early reading instruction for all students, including students with reading problems, students who are ELs, and advanced readers. School psychologists are well positioned to understand the common goals of schoolwide approaches to early reading instruction and assessment. Implications for Practicing School Psychologists (cont.) School psychologists are aware of the predictive information derived from ORF, and also that like ORF is not sensitive to skill differences among students in kindergarten and through the first half of first grade (Baker, Plasencia-Peinado, & Lezcano-Lytle, 1998; Fuchs, Fuchs, Hamlett, Walz, & Germann, 1993). Waiting until the end of first grade to assess which children are at risk for reading difficulties limits the ability of schools to intervene strategically during a valuable period of instructional time. One solution, of course, is to assess students in kindergarten and the first part of first grade on measures that reliably and validly identify the best student candidates for interventions. Implications for ELs This study supports other research on the use of fluencybased measures (e.g., curriculum-based measurement, Fuchs, 2004) to assess important early academic skill with ELs. A study on the use of ORF with ELs in second grade found that the measure functioned similarly with Spanish-speaking ELs and ESs (Baker & Good, 1995). More recently, Wiley and Deno (2005) found that correlations between ORF and performance on a state reading test were higher in grade 3 for ESs than Hmong speaking ELs and were higher in grade 5 for ELs than ESs. However, Baker and Good (1995) and Wiley and Deno (2005) did not speculate on how schools might use their findings to interpret the reading performance of ELs and ESs. Implications for ELs The findings of the current study suggest that schools teaching ELs to read in English should consider interpreting the performance on a pseudoword reading measure such as NWF similarly for ELs as ESs. If ELs are being taught to read in English, this study suggests that problematic performance on NWF could be interpreted similarly for ELs and ESs. Difficulty decoding pseudowords may be attributable to a student not having received sufficient instruction in the alphabetic principle. The various underlying causes of a student’s difficulty may vary, and instructional solutions may vary but the ultimate goal should remain the same. Implications for ELs Our best knowledge about how to help EL students instructionally is to focus on teaching them how to apply the alphabetic principle in reading This reading strategy should be applied consistently, systematically, confidently, and intelligently. Our efforts to provide the type of instruction students need should be evaluated regularly (i.e. progress monitoring). The intensity of our instructional efforts should be increased regularly and systematically, to give students the best chance to master the alphabetic principle as quickly as possible. Limitations A primary limitation of this study is that all of the participating schools were in Reading First. Whether these findings would be comparable with nonReading First schools is unknown. In addition, these findings are anchored to schools that are implementing scientifically-based reading instruction. It is unknown if these findings would be comparable in schools that deliver reading instruction that varies from approaches that stress explicit instruction in essential reading elements. Another limitation is that these findings are based on one state and one high stakes reading measure, the SAT-10. We do not know if these results would be similar in other states and with other types of high-stakes reading measures (e.g., Iowa test of Basic Skills). Directions for Future Research This study represents a first step in a series of studies to examine the use of NWF as a screening and progress monitoring tool. Fuchs (2004) recommends three stages for “substantiating the tenability” of a given progress monitoring tool. Stage one involves the investigation of performance at one point in time. According to this framework, this current study would be characterized as a stage 1 investigation. Stage two involves investigation into the technical features of slope or progress over time. Thus, future research on NWF should investigate how students grow on NWF over time and the relation between growth and performance on important outcome measures and for important subgroups of students. Directions for Future Research (cont.) In stage three, the instructional utility of a measure is studied. We have preliminary evidence that the large scale implementation of NWF in Reading First is associated with yearly gains on end-of-year NWF and ORF outcomes, and on yearly increases on the SAT-10 and the state reading test (Baker et al., 2007). Future research with ELs should explore the interaction between instructional quality and responsiveness to instruction as measured by NWF and other formative measures. Conclusions Evidence from this study supports the use of NWF in the early grades to screen students for reading problems. Using data to intervene early and strategically is a major assessment activity expected by schools in Reading First as well as schools using RtI. In our view, one strength of Reading First is the use of a comprehensive assessment framework for making decisions about students and program impact. This study provides evidence that NWF offers a robust index of early reading proficiency for students in grades K-1, including ELs and ESs.