Southern Gothic

advertisement

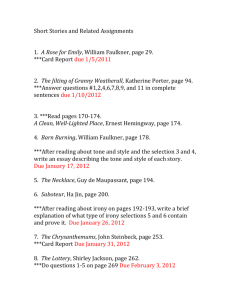

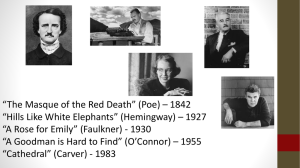

SOUTHERN GOTHIC English 1302 SOUTHERN GOTHIC Southern Gothic Literature is a sub-genre of gothic literature (think Poe and Shelley) unique to American literature that takes place exclusively in the American South. Focuses on character, social, and moral shortcomings in the American south; it reached its height between 1940-1960s. Notable Southern Gothic authors include: Flannery O’Conner, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, William Faulkner, and Carson McCullers. ORIGIN Elements of a gothic treatment of the South were apparent in the 19th century, ante- and post-bellum, in the grotesques of Henry Clay Lewis and the de-idealised visions of Mark Twain. The genre came together, however, only in the 20th century when Dark Romanticism, Southern humour, and the new Naturalism merged into a new and powerful form of social critique. Images of the Great Depression inspired Photographer Walker Evans to claim: "I can understand why Southerners are haunted by their own landscape." Dorothea Lange's “Migrant Mother” depicts destitute pea pickers in California, centering on Florence Owens Thompson, age 32, a mother of seven children, in Nipomo, California, March 1936. CHARACTERISTICS deeply flawed, disturbing or eccentric characters who may or may not dabble in hoodoo ambivalent gender roles and decayed or derelict settings grotesque situations sinister events relating to or coming from poverty, alienation, racism, crime, and violence. CHARACTERISTICS drafty castles laced with cobwebs secret passages frightened, wide-eyed heroines whose innocence does not go untouched Comments on society’s negatives or weaknesses to point out truths of America’s southern culture Often disturbing but realistic THE GROTESQUE A character’s negatives/undesirable characteristics allow the author to show/comment on unpleasant aspects of southern culture—racial bigotry, crushing poverty, violence, moral corruption or ambiguity. Something physical in the setting is unusual and often broken Carson McCullers observes that Southern writers frequently juxtapose “the tragic with the humorous, the immense with the trivial, the sacred with the bawdy, the whole soul of man with a materialistic detail.” TENNESSEE WILLIAMS He was brilliant and prolific, breathing life and passion into such memorable characters as Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalski in his critically acclaimed A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE. And like them, he was troubled and self-destructive, an abuser of alcohol and drugs. He was awarded four Drama Critic Circle Awards, two Pulitzer Prizes and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He was derided by critics and blacklisted by Roman Catholic Cardinal Spellman, who condemned one of his scripts as “revolting, deplorable, morally repellent, offensive to Christian standards of decency.” He was Tennessee Williams, one of the greatest playwrights in American history. (PBS.com) (March 26, 1911-February 25, 1983) The Glass Menagerie (1944) In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel (1969) A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) Will Mr. Merriweather Return from Memphis? (1969) Summer and Smoke (1948) Small Craft Warnings (1972) The Rose Tattoo (1951) The Two-Character Play (1973) Camino Real (1953) Out Cry (1973, rewriting of The Two-Character Play) Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955) The Red Devil Battery Sign (1975) Orpheus Descending (1957) This Is (An Entertainment) (1976) Suddenly, Last Summer (1958) Vieux Carré (1977) Sweet Bird of Youth (1959) A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur (1979) Period of Adjustment (1960) Clothes for a Summer Hotel (1980) The Night of the Iguana (1961) The Notebook of Trigorin (1980) The Eccentricities of a Nightingale (1962, rewriting of Something Cloudy, Something Clear (1981) Summer and Smoke) A House Not Meant to Stand (1982) The Milk Train Doesn't Stop Here Anymore (1963) In Masks Outrageous and Austere (1983) The Mutilated (1965) The Seven Descents of Myrtle (1968, aka Kingdom of Earth) A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE Blanche DuBois A sensitive, delicate moth-like member of the fading Southern aristocracy who visits her sister in New Orleans. Mystery surrounds her throughout much of the play. Stella Kowalski Blanche's sister who is married and lives in the French Quarter of New Orleans. She has forgotten her genteel upbringing in order to enjoy a more common marriage. Stanley Kowalski A rather common working man whose main drive in life is sexual and who faces everything with brutal realism. He is a true man of his time. Harold Mitchell (Mitch) Stanley's friend who went through the war with him. Mitch is unmarried and has a dying mother for whom he feels a great devotion. Eunice and Steve Hubell The neighbors who quarrel and who own the apartment in which Stella and Stanley live. They live on the second level, while the Kowalskis live on the ground floor. ELEMENTS TO NOTICE Music Colors, light (present or absent= truth) Names of people, places, things Gestures Culture clashes Flashbacks WILLIAM FAULKNER September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962 American writer and Nobel Prize laureate from Oxford, Mississippi. Faulkner is one of the most important writers in both American literature generally and Southern literature specifically. Two of his works, A Fable (1954) and his last novel The Reivers (1962), won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.[2] The Sound and the Fury (1929), As I Lay Dying (1930), Light in August (1932), Absalom, Absalom! (1936) FAULKNER Southern Gothic often hinged on the belief that daily life and the refined surface of the social order were fragile and illusory, disguising disturbing realities or twisted psyches. Faulkner, with his dense and multilayered prose, traditionally stands outside this group of practitioners. However, “A Rose for Emily” reveals the influence that Southern Gothic had on his writing: this particular story has a moody and forbidding atmosphere; a crumbling old mansion; and decay, putrefaction, and grotesquerie. “A ROSE FOR EMILY” First published in the April 30, 1930 issue of Forum. The story takes place in Faulkner's fictional city, Jefferson, Mississippi, in the fictional county of Yoknapatawpha County. It was Faulkner's first short story published in a national magazine. Resistance to change: the most recurrent theme in the story. WILLIAM FAULKNER SPEAKS ON “ROSE" IN 1955: I feel sorry for Emily's tragedy; her tragedy was, she was an only child, an only daughter. At first when she could have found a husband, could have had a life of her own, there was probably some one, her father, who said, "No, you must stay here and take care of me." And then when she found a man, she had had no experience in people. She picked out probably a bad one, who was about to desert her. And when she lost him she could see that for her that was the end of life, there was nothing left, except to grow older, alone, solitary; she had had something and she wanted to keep it, which is bad—to go to any length to keep something; but I pity Emily. I don't know whether I would have liked her or not, I might have been afraid of her. Not of her, but of anyone who had suffered, had been warped, as her life had been probably warped by a selfish father . . . [The title] was an allegorical title; the meaning was, here was a woman who had had a tragedy, an irrevocable tragedy and nothing could be done about it, and I pitied her and this was a salute . . . to a woman you would hand a rose. From Faulkner at Nagano, ed. Robert Jelliffe (Tokyo: Kenkyusha Ltd., 1956), pp. 70–71. BARN BURNING Written at the ebb of the 1930s, a decade of social, economic, and cultural tumult—the decade of the Great Depression Set in the post-Civil War South, Faulkner creates a family that is at once self-centered and cunning. This is a story of one man's conviction regarding the righteousness of his own actions and the life-altering decisions this creates for his youngest son's (Sarty) sense of decency as it conflicts with his sense of loyalty to the family. FLANNERY O’CONNOR March 25, 1925 – August 3, 1964 She was a Southern writer who often wrote in a Southern Gothic style and relied heavily on regional settings and grotesque characters. O'Connor's writing also reflected her own Roman Catholic faith, and frequently examined questions of morality and ethics. “A GOOD MAN IS HARD TO FIND” The short story was first published in 1953 in the anthology Modern Writing I Irony, religious overtones, grotesque… must read to find out more! “GOOD COUNTRY PEOPLE” In "Good Country People," O'Connor uses irony and a finely controlled comic sense to reveal the world as it is - without vision or knowledge. As in O'Connor's story "A Good Man is Hard to Find," a stranger - deceptively polite but ultimately evil - intrudes upon a family with destructive consequences. In Hulga's case, despite her advanced academic degrees, she is unable to recognize evil until it is too late.