File - El Jefe Cardona

Running Head: A POSITION OF NEUTRALITY FOR SCHOOL PRAYER

A Position of Neutrality

For School Prayer

Charles E. Cardona II

M01059763

Middle Tennessee State University

1

A POSITION OF NEUTRALITY FOR SCHOOL PRAYER

A Position of Neutrality for School Prayer

The free practice of religion is one of the most deeply held beliefs of American society.

2

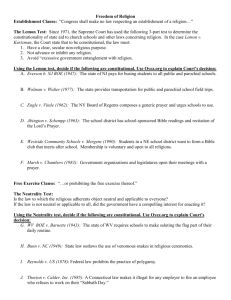

Codified in the U.S. constitution, the First Amendment guarantees “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…” Obviously, the years of court cases and their subsequent interpretations by the legal system has further detailed the meaning and intent of this amendment. As it affects the daily lives of American citizens, one of the most contentious areas affected by the First Amendment is that of school prayer. While citizens are free to worship as much--or as little--as they wish, the part of the First

Amendment that deals with religion in American society, also known as the Establishment

Clause, clearly ties the hands of governments. What has caused the most legal trouble in interpreting the First Amendment is not the independent student practice of religion in public schools, but when school systems and their employees cross the bounds of neutrality and take actions that can be seen as dealing with religious practices either negatively or positively.

Federal, state and local entities are prohibited from promoting or restricting religion. The

Founding Fathers wrote the Establishment Clause recognizing what happens when government and religion are intertwined. When the two are joined as essentially one regime, the corruption of both is extremely possible. As the Pilgrims sailed away from England, they sought a new life free of religious persecution by the government that only permitted certain beliefs.

Public schools are without question a part of government. Attendance is compulsory and universal. In the United States, all manners of people with wide-ranging beliefs attend, are employed by, or interact with public schools every day. As the court cases concerning the promotion or restriction of religion have piled up, it is quite clear that government and schools have a responsibility to remain neutral in order to protect the influences of the majority and the

A POSITION OF NEUTRALITY FOR SCHOOL PRAYER minority from not only each other, but also from the possible consequences of straying from neutrality. A number of Supreme Court cases refine and reinforce the concept of government

3 neutrality towards religion found in the First Amendment.

The appearance of religion and prayer in public schools has not always been adversarial.

In 1947, the case of Everson v. Board of Education stemmed from policy of the New Jersey school district in the township of Ewing that paid for Catholic school students’ bus fare to and from their school. This practice was found in violation of the Establishment Clause. While it is not a strict case of prayer in public school and it does not condemn attendance at parochial school, this case is about government neutrality toward religion being discarded violated. For the government to provide a way for students to get to the religious school shows favoritism toward religious practice. In paying for the bus fare for these students, the school board was using tax money to help promote, even if that was not the program’s intent, religious instruction.

While the program in the Everson case was struck down, religious practice and public schools were allowed to work in concert in the case of Zorach v. Clauson (1952). The schools of

New York City used to have a “release time” for students, if they had their parents’ permission, to go to “religious centers for religious instruction or devotional exercises.” Attendance was taken at these centers and reported to the schools. It might seem that this would be an endorsement of religion during school hours, but attendance was voluntary, transportation not provided and most importantly, did not occur on the school grounds. The Supreme Court deemed it acceptable. By allowing time for religious practice, recognized as deeply important for many, the school system does not endorse religion but also does not restrict the personal beliefs of those who desire religious instruction. The most important elements are the location and disposition of the participants: not at school and voluntary.

4

A POSITION OF NEUTRALITY FOR SCHOOL PRAYER

Within the boundaries of school, students must have a legitimate choice of when and how they choose to participate in religious activities. School attendance is mandatory and there is no other option but to attend school. Without choice, students can feel pressured to join such activities because of the schools’ position of authority. They may even feel peer pressure to join.

That pressure was addressed in these Supreme Court cases.

In Engle v. Vitale (1962), the New Hyde Park, New York, the school system mandated that each day began with a prayer that was composed by the Board of Education: “Almighty

God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our Country.” This prayer was recommended by the State Board of

Regents, the governmental body for education in New York state. Being composed by government officials and with students ordered to recite it, the violation of the neutrality of the

First Amendment was clear. The practice of mandated prayer was rescinded.

In the similar case of School District of Abington Township, PA v. Schempp (1963), the school was following Pennsylvania law: “At least ten verses from the Holy Bible shall be read, without comment, at the opening of each public school on each school day. Any child shall be excused from such Bible reading, or attending such Bible reading, upon the written request of his parent or guardian.” While this law seems to have an “out” for those who did not want to participate, the violation is clear: the practice is prescribed by the state. In bringing the case to court, the Schempp family felt the practice not only violated their Unitarian beliefs about nonpublic prayer, but that their children, if excused, would be labeled as “oddballs,” or considering the time of the case, “communists.” This practice was struck down.

Politics can also have a hand in violating neutrality. In the case of Wallace v. Jaffree

(1985), an Alabama statute as first written did not violate the First Amendment. It simply

A POSITION OF NEUTRALITY FOR SCHOOL PRAYER allowed for a time for “meditation.” However, when the law was amended twice, that brought

5 the government into a violation of impartiality. The first revision added the phrase “voluntary prayer” and the second authorized teachers to lead “willing students” in a prayer that was prescribed. In fact, the legislative sponsor of the revisions stated that his purpose was to bring prayer back to public schools. When the government overstepped the bounds of impartiality and gradually moved toward a promotion of religion some students possibly faced exclusion for nonparticipation and this is not acceptable. The revisions were deleted.

In Lee v. Weisman (1992) in Providence, Rhode Island, a rabbi was invited to give a nonsectarian prayer at a middle school graduation ceremony. While this might sound like the beginning of a great joke, a friend of a student objected to this school-sanctioned religious display. Because the ceremony was held at the school, this was violation of neutrality.

Furthermore, the student in question could not just avoid graduation. This special time, even if it is a middle school graduation, should not violate the beliefs of the minority.

The prior cases were violations of the government’s stance on impartiality towards religion and prayer in schools. When the religious practice is not propagated or restricted by the school administration or government and is student-led, there is no problem.

In Santa Fe I.S.D. v. Doe (2000), these tenets were violated. In this school district in Texas, there was regular proselytizing activity in the school setting: prayers over the public address at sporting events, delivery of Gideon bibles to the school’s students and even disparagement of other religions.

What set these activities apart were school board policies and procedures in place to promote or permit the activities. This clearly violated the responsibility the government had in remaining neutral towards religion and the practices were stopped.

A POSITION OF NEUTRALITY FOR SCHOOL PRAYER

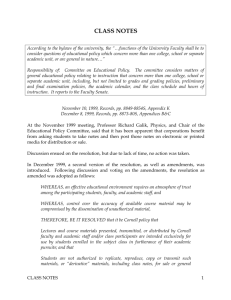

As the federal laws trump states’ laws, a similar concept applies in Tennessee law where

6 state law overrules local statute or regulation. In Tennessee, the law found in Tennessee Code

Annotated 46-6-2901-2906 (1997) is clear and applies to all school districts: “public schools neither advance nor inhibit religion.” In very practical and straightforward language, this law wishes to avoid any confusion on the interpretation of what neutrality means and to avoid litigation. It delineates several things, including what is expected of students in the practice of their religion: to not disturb the learning process or the rights of others. It also lays out the steps for student grievance that only end in court after the appropriate steps have been taken with school and system administration.

Finally, the law clearly defines the roles of any employee of a public school: “Nothing in this part shall be construed to support, encourage or permit a teacher, administrator or other employee of the public schools to lead, direct or encourage any religious or antireligious activity in violation of that portion of the first amendment of the United States constitution prohibiting laws respecting an establishment of religion.” (49-6-2906) By structuring the law plainly, the state’s intent is easily understood. Schools are to be neutral concerning religious matters.

All the previous examples are meant to clarify the concept of governmental neutrality towards religion and prayer. With so many different systems of belief, or even non-belief, the government is supposed to be impartial and to protect the freedom to live as one chooses. For as the Supreme Court of Ohio Justice Alphonso Taft said in ruling about the use of the Bible by teachers in Minor v. Board of Education of Cincinnati (1872): “The government is neutral and while protecting all, it prefers none, and it disparages none.”

A POSITION OF NEUTRALITY FOR SCHOOL PRAYER

References

First Amendment. (1787) In United States Constitution online, Legal Information Institute,

Cornell University Law School. Retrieved from http://topics.law.cornell.edu/constitution/billofrights#amendmenti

Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1. (1947) In U.S. Supreme Court Center, Justia.com.

Retrieved from http://supreme.justia.com/us/330/1/case.html

Zorach v. Clauson, 343 U.S. 306. (1952) In Supreme Court online, Legal Information Institute,

Cornell University Law School. Retrieved from http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0343_0306_ZO.html

7

Engle v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421. (1962) In Supreme Court online, Legal Information Institute,

Cornell University Law School. Retrieved from http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0370_0421_ZO.html

School District of Abington Township, PA v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203. (1963) In Supreme Court online, Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School. Retrieved from http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0374_0203_ZS.html

Wallace v. Jaffree, 472 U.S. 38. (1985) In Supreme Court online, Legal Information Institute,

Cornell University Law School. Retrieved from http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0472_0038_ZO.html

Lee v. Weisman, (90-1014), 505 U.S. 577. (1992) In Supreme Court online, Legal Information

Institute, Cornell University Law School. Retrieved from http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/90-1014.ZO.html

A POSITION OF NEUTRALITY FOR SCHOOL PRAYER

Santa Fe I.S.D. v. Doe, (99-62) 530 U.S. 290. (2000) In Supreme Court online, Legal

Information, Cornell University Law School. Retrieved from http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/99-62.ZS.html

Tennessee Code Annotated 46-6-2901-2906. (1997) In Michie’s Legal Resources. Retrieved

8 from http://michie.com/tennessee/lpext.dll?f=templates&fn=main-h.htm&cp=tncode

Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Released Time. (n.d.) In CRS

Annotated Constitution, Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School.

Retrieved from http://www.law.cornell.edu/anncon/html/amdt1toc_user.html

Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Prayers and Bible Reading. (n.d.)

In CRS Annotated Constitution, Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law

School. Retrieved from http://www.law.cornell.edu/anncon/html/amdt1toc_user.html

Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Curriculum Restriction. (n.d.) In

CRS Annotated Constitution, Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law

School. Retrieved from http://www.law.cornell.edu/anncon/html/amdt1toc_user.html