Chapter 10 Law and Political Economy Sadly, Father's Bible failed to

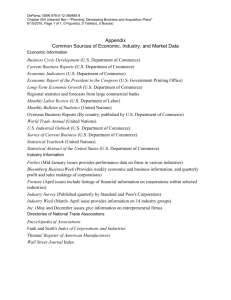

advertisement