Kill or Cure

advertisement

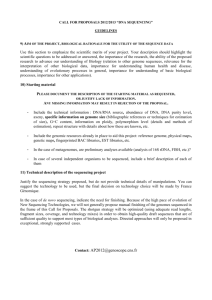

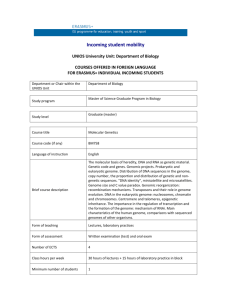

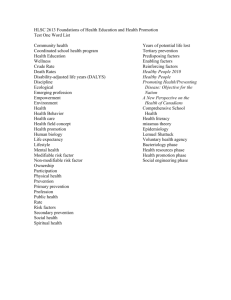

Kill or Cure Medicine in the West: the rise of science Aims • To introduce the idea and impact of laboratory medicine. • To see how the laboratory provided the context for the development of bacteriology. • To think about the role played by bacteriology in the shift from ‘dirt to germs’ in theories of disease causation. • To explore the history of genetics and its effects on modern medicine. Part one • The rise of laboratory medicine Introduction to laboratory medicine • From the latter half of the 18th C western medicine witnessed fundamental changes. These were evident in medical theory: the ways in which the workings of the body in health and disease were understood. • The spaces in which medical knowledge was developed and applied also underwent transformation. Laboratory medicine sought to explain the structure of the body at the cellular level and to describe its function as a complex series of dynamic processes. • The laboratory usurped the hospital as the locus of research, and the laboratory scientist claimed a greater authority than the clinical practitioner. The diagnosis of particular infectious diseases now relied on tests on tissue samples performed at the lab bench, not simply on the subjective analysis of patterns of symptoms. • These changes that occurred were complex and interrelated. They proceeded at various rates in different parts of the western world. Learning from the laboratory The rising sciences of life: • Cell biology and pathology ( bacteriology and parasitology) • Physiological chemistry ( experimental physiology) • Pharmacology Nicholas Jewson, ‘The disappearance of the sickman from medical cosmology, 1770-1870’, Sociology, (1976) 10; 22544. Techniques: • Microscopy • Histology • Vivisection Tools: • Microscope • Sphygmograph • Spirometer • Thermometer • Scales, etc. c. 1850s, esp. Germany Part two • The ‘discovery’ of bacteria Bacteriology • Bacteriology is the study of bacteria. • Roy Porter argues that the development of bacteriology in the latter part of the 19th C brought one of medicine’s few true revolutions. • The general thinking behind bacteriology (that diseases is due to tiny invasive beings) was not new (theories of contagion maintained that disease entities were passed from the infected party to others). • However it was only in the 19th C that the rise of pathoanatomy led to the belief that specific parasites and bacteria would be responsible for particular diseases. Pasteur and Koch Louis Pasteur 1822-1895, a French chemist and biologist who proved the germ theory of disease and invented the process of pasteurisation. Robert Koch 1843-1910, a German physician and pioneering microbiologist. The founder of modern bacteriology. ‘Magic bullets’ • A magic bullet is a perfect drug to cure a disease with no danger of side effects. The term magic bullet was first used in this sense by the German physician and scientist Paul Ehrlich who received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1908. • Initially, Ehrlich invoked the notion of a magic bullet in characterizing antibodies. He then reused the concept of a magic bullet to apply to a chemical that binds to and specifically kills microbes or tumor cells. • Ehrlich's best known magic bullet was arsphenamine (Salvarsan, or compound 606), the first effective treatment for syphilis. At a meeting in 1910, Ehrlich and his colleagues announced the remarkable effects of their treatment of syphilis with this magic bullet. Koch’s postulates • The organism suspected of causing a particular disease could be discovered in every instance of the disease. • When extracted from the body, the germ could be grown in the laboratory and maintained for several generations. • When this culture was injected into animals, it should induce the same disease observed in the original source. • The organism could then be retrieved from the experimental animal and cultured again. Part three • From ‘dirt’ to ‘germs’ Miasma Malaria, a disease transmitted by mosquitoes and still widespread in many tropical areas of the world, was once endemic in temperate latitudes. La Mal’aria, by A. Hebert, which hangs in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, shows a group of people in the Pontine marshes as a result of malaria. Prior to the late 19th C it was assumed that the disease emanated directly from evil-smelling marshes – hence the name ‘mal’aria’, literally meaning ‘bad air’. Cholera John Snow, Broad Street Pump, 1855 John Snow (1813-1858) observed a correlation between the disease and where it spread, and with the source of public water. In 1855, he published On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. This treatise was a milestone in public health as it correctly identified the fecal-oral route of human infection and offered powerful arguments for the germ theory. Bacteriology and the ‘grand research institutes’ The Pasteur Institute, Paris, 1888. The institute was built in Paris in 1888 both to honour the work of Louis Pasteur and to provide a base for his further research. Bacteriology and disease control • Firstly the discovery of the identity of disease-causing pathogens gave rise to hopes that particular complaints could be prevented and treated by new vaccine therapies. Louis Pasteur and the rabies cure, 1885 • Secondly bacteriology enabled disease control through the isolation of infected persons. While isolation was not new, bacteriological tests gave authorities accurate knowledge of the identity and presence of disease. London Open Air Sanatorium for Tuberculosis, c.1907 Sanitary reform and public health Max von Pettenkofer (1818-1901). Pettenkofer’s name is most familiar in connection with his work in practical hygiene, as an apostle of good water, fresh air and proper sewage disposal. His attention was drawn to this subject by the unhealthy condition in Munich in the 19th century. Part four • From ‘germs’ to ‘genes’ Founding fathers Gregor Johann Mendel (1822-1884). A scientist and Augustinian friar. Published ‘Experiments in Plant Hybridization’ in1865. The ‘founder’ of the modern science of genetics. He discovered the basic principles of heredity through experiments breeding plants. He showed that some traits such as height or flower color do not appear blended in their offspring. His work also demonstrated that variations in traits were caused by variations in inheritable factors. Charles Robert Darwin (1809-1882). An English naturalist and geologist, best known for his contributions to evolutionary theory. Published the Origin of Species in 1859. The rise of Darwinism also led to the advancement of eugenics. Darwin had concluded his explanations of evolution by arguing that the greatest step humans could make in their own history would occur when they realized that they were not completely guided by instinct. Rather, humans, through selective reproduction, had the ability to control their own future evolution. Mendel’s heirs • The word gene was first used in 1909 by the Danish botanist Wilhelm Johannsen to describe the Mendelian units of heredity. • The American geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan studied the segregation of mutations in the fruit fly. Morgan used mutations to move beyond the laws that managed heredity to examine the specific mechanisms—the genes themselves— that carry out the process. By finding and breeding hundreds of visible mutants, including those with variations in body color and wing shape, he created chromosome maps that showed where on each of the fruit fly’s 4 chromosomes certain genes lay. • The fact that genetic linkage corresponded to physical locations on chromosomes was shown later, in 1929, by Barbara McClintock, in her cytogenetic studies on maize. Illustration from Morgan’s, A Critique of the Theory of Evolution (1916) DNA One of Watson and Crick’s original models for the structure of DNA. James Watson and Francis Crick, 1959 • In the 1950s, at the Cavendish Laboratories in Cambridge, England, scientists developed X-ray crystallography, a technology that made it possible to interpret the threedimensional structure of a crystallized molecule. • It allowed Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin to take "snapshots" of DNA that were used in 1953 by James Watson and Francis Crick to build their now-famous model: DNA was shaped like a spiral staircase, or double helix. • Their discovery of the actual physical structure of DNA finally created a consensus among geneticists that genes were real. The age of molecular genetics • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1970 - Arber and Smith - First restriction enzyme, Hind II, is isolated 1970 - Baltimore and Temin - Discovery of reverse transcriptase 1972 - Berg - First recombinant DNA molecule is constructed 1973 - Boyer and Cohen - First functional recombinant E. coli cell produced 1977 - Sanger and Gilbert - DNA sequencing techniques are described 1977 - Sharp and Roberts - Introns discovered 1978 - Botstein - RFLPs launch the era of molecular mapping of linkage groups 1980 - Sanger Group - First genome is sequenced, the bacteriophage ΦX174 of E. coli 1983 - Mullis - PCR technique is discovered 1986 - Hood, Smith, Hunkapiller and Hunkapiller - First automated DNA sequencer 1990 - US Government - Human Genome Project launched 1995 - Celera - First bacterial genome (H. influenza) is sequenced 1996 - Yeast Genome Consortium/ First eukaryotic genome (yeast) sequenced 2000 - Arabidopsis Genome Initiative - First flowering plant genome (Arabidopsis thaliana) is sequenced 2001 - The human genome sequence is published The new eugenics? • Medical genetics encompasses a wide range of health concerns, from genetic screening and counseling to fetal gene manipulation and the treatment of adults suffering from hereditary disorders. • Applications of the Human Genome Project are often referred to as “Brave New World” genetics or the “new eugenics”. Conclusions • The advent of bacteriology was transformative in understanding of diseases. • However the extent to which bacteriological science led to the decline in epidemic disease is harder to assess. • New germ practices were used alongside old sanitary reforms. • The transformation of genetic medicine from a marginal field in the 1950’s to a core activity of biomedicine was a major development in modern science. • The past two decades we have witnessed an increase and more intense focus on the genetic and biological basis for disease. • However at least the 18th C scientists, doctors and patients had tried to establish links between heredity and disease.