Miller vs. Alabama Court Case

advertisement

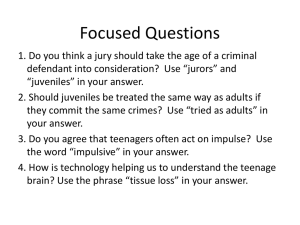

Miller v. Alabama Argued: March 20, 2012 Decided: June 25, 2012 Background Juvenile crime is a problem throughout the country, and most states have enacted laws allowing offending juveniles to be prosecuted as adults for serious crimes. The Supreme Court has previously ruled that the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits “cruel and unusual punishment,” prevents states from applying certain punishments, including the death penalty, to juveniles. This case addresses the issue of whether sentencing a 14-year-old homicide offender to life in prison with no chance for parole is also a violation of the Eighth Amendment. Facts When Evan Miller was 14, he and his 16-year-old friend Colby Smith killed Miller’s neighbor, Cole Cannon. While at Cannon’s house, an altercation occurred, which may have been the result of an attempt by the boys to steal money from Cannon’s wallet. During the dispute, Cannon grabbed Miller by the throat. Smith then hit Cannon over the head with a baseball bat. Miller continued hitting Cannon with either the bat or his fists. Miller and Smith left Cannon alive on the floor of his trailer but later returned. They set several fires throughout the trailer and left Cannon to die. Both boys eventually confessed to the murder during questioning by police. Smith pled guilty and agreed to testify against Miller in exchange for a sentence of life with the possibility of parole. In the juvenile court system, the maximum punishment is detention until the age of 21. Alabama law allows juveniles to be tried in adult court if the District Attorney believes that the sentence imposed by a juvenile court would not be sufficient in light of the crime committed. Miller was tried as an adult and found guilty of aggravated murder, for which the allowed sentences in Alabama are death or life without parole. In Roper v. Simmons, the Supreme Court ruled that death sentences for juveniles under age 18 violated the Eighth Amendment, so the sentence of life without parole was given by default. Issue Does a sentence of life without parole for a 14-year-old convicted of murder violate the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishments? Constitutional Amendment and Precedents Eighth Amendment “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.” Harmelin v. Michigan (1991) Under Michigan law, the crime of possession of more than 650 grams of cocaine resulted in mandatory life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. Harmelin challenged this, saying that it was cruel and unusual in violation of the Eighth Amendment. The Supreme Court upheld Harmelin’s sentence. They said that while certain mandatory punishments could be severe, they were not unusual since mandatory punishments have been enacted by legislatures since the founding of the United States. Roper v. Simmons (2005) Simmons was sentenced to death for a murder committed when he was 17. He argued that the death penalty was a cruel and unusual punishment for a crime committed by an immature and irresponsible juvenile. The Supreme Court agreed with him, saying that, since a majority of the states had rejected the death penalty for juveniles, there was a national consensus that it was a cruel or unusual punishment. Graham v. Florida (2010) Seventeen-year-old Terrance Graham was on probation when he committed a robbery at gunpoint and led police in a car chase. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole. The Supreme Court overturned this sentence, saying that giving life without parole to juvenile offenders who had not committed a homicide was cruel and unusual punishment. The Court noted that juvenile offenders had limited moral culpability and that current sentencing practices rarely imposed life without parole on juvenile non-homicide offenders anyway, indicating a consensus against the practice. Arguments for Miller Children are different from adults in several important ways. They lack developmental maturity, are impulsive, are susceptible to outside influences, and have greater capacity than adults to change their behaviors. Hundreds of state and federal laws recognize this distinction and give children limited rights and responsibilities. These unique characteristics are at odds with the idea of a punishment that declares an offender to be forever unfit for society. Life without parole is essentially the same as a death sentence, which was rejected for juveniles by Roper v. Simmons. Miller is not asking to be let free, he is asking for life in prison with the chance of parole. This doesn’t mean he will ever necessarily be out of prison; it just gives him the chance of freedom at some point in the future if a parole board feels that he is no longer a danger to society. Most state legislatures allow for life without parole for juveniles only because they don’t have specific laws saying otherwise. Many laws that allow for juveniles to be waived into adult court don’t differentiate between a 17-year -old and a 10–year-old. Among the states that have directly addressed the issue of life without parole for juveniles, however, almost every one has set the age above 14. Only one state that has set a minimum age for life without parole has set that age younger than 15. The near absence of direct legislative approval for this type of punishment indicates a national consensus, demonstrating that society believes the punishment is cruel and unusual. There are only 79 prisoners in the United States serving a life without parole sentence for crimes committed at age 13 or 14, and 90% of those received life without parole as a mandatory sentence with no discretion allowed to the judge or jury. The extremely rare imposition of this punishment, even where it is technically allowed, shows that there is a national consensus against it. In the criminal justice system, the defendant is subjected to unfamiliar proceedings and required to make many important decisions regarding his or her defense. A 14-year-old is not equipped to understand how the system works and is more likely than an adult to sabotage or otherwise weaken his or her own case. Life without parole is not an effective deterrent because juveniles are less oriented to the future than adults. It is also a greater punishment when applied to children than when applied to adults because it will likely be a much longer punishment for juveniles. Arguments for Alabama The death penalty and life in prison without parole are fundamentally different. Structuring the method and environment in which someone will live should not be equated with depriving them of their life. Thirty-nine states allow a 14-year-old to be sentenced to life without parole when he or she is guilty of aggravated murder. Of the 39 states that allow for a 14-year-old to be sentenced to life without parole, 26 of those states have made life without parole the minimum punishment possible for aggravated homicide. These factors indicate a strong national consensus that this punishment is not cruel and unusual. Throughout history, civilized societies have viewed aggravated murder as one of the most heinous crimes imaginable. To give a person who commits such a crime the opportunity to live free again is enormously dangerous to society and takes an intense emotional toll on the victim’s family each time the offender has a parole hearing. The age of a 14-year-old defendant already allows him a lesser sentence. If he were an adult he would have been eligible for the death penalty. It is appropriate, due to the differences inherent between adults and children, to allow for the lesser punishment of life without parole. His age should not, however, force his maximum sentence to be automatically lowered twice. The rare imposition of the punishment is only a result of the rare occurrence of juveniles committing crimes of this severity. In 2007, only 135 juveniles under the age of 15 were arrested for homicide offenses. Most states rightly require a mandatory sentence of life without parole for those who commit aggravated murder. A mandatory punishment shows that society as a whole, and not just a single jury, has decided that a crime is so severe that its punishment should not be determined on a case by case basis. Since a determination of whether a punishment is cruel or unusual is largely a function of consensus, the courts should defer to the people when they have collectively established such a clear and unequivocal system of punishment. Decision The Court ruled in a 5-4 decision that states could not impose a mandatory life without parole sentence on juveniles under the age of eighteen. Justice Kagan wrote for the majority and was joined by Justices Kennedy, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor. Justice Breyer wrote a concurring opinion joined by Justice Sotomayor. Justice Roberts wrote a dissenting opinion that was joined by Justices Scalia, Thomas, and Alito. Justices Thomas and Alito also wrote dissenting opinions that were each joined by Justice Scalia. Majority The majority said that the precedents in Roper and Graham indicated that juveniles are different from adults and that the type of crime committed does not change this fundamental difference. According to studies relied on by the Court, children lack maturity, are more vulnerable to outside influences such as peer pressure, and are more likely to be capable of change. Since mandatory sentencing makes it impossible for a judge to take into account these differences between adults and children, the Court said, mandatory sentences of life without parole violate the Eighth Amendment. Life without parole sentences may still be imposed on juveniles, as long as they are sentenced individually and not under mandatory sentencing rules. The state argued that there was a national consensus that mandatory life without parole for juveniles was not cruel and unusual because 26 states had the same mandatory sentencing laws in place. The Court disagreed, saying that the legislatures of those states certainly did not intend for 14-year-olds to be sentenced to life without parole. It is more likely, the Court says, that the legislatures did not think of this type of unintended consequence when they enacted two separate provisions: mandating life without parole sentences for certain offenses and allowing juveniles to be tried in adult court. The Court said that a state legislature’s criminal laws don’t have to guarantee eventual freedom for juvenile homicide offenders, but that there must be some meaningful opportunity for release that the judge may offer at his or her discretion. This allows a judge the ability to better take into account the many complex factors associated with juveniles. Dissent The dissents said that the precedent in Harmelin v. Michigan should have applied to this case. Mandatory sentences, they reasoned, are not cruel and unusual simply because they are mandatory. It may be that juveniles are different from adults. This should not, in the dissenters’ view, take away the ability of democratically elected legislatures to require life without parole for juveniles who commit the worst type of murder. The logic in Graham is not binding in this case, they said, because the opinion in Graham said clearly that murder was substantially different from non-homicide offenses and could be given greater punishments. The dissent concludes that, even if members of the Court may disagree with the acts of a legislature, it is not the Court’s place to make what are essentially legislative decisions.