Ryan Henry - Indiana University Computer Science Department

advertisement

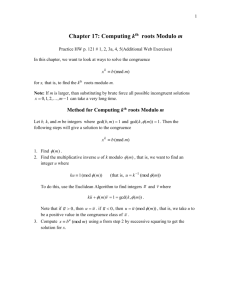

I538/B609:

Introduction to

Cryptography

Fall 2015 · Lecture 18

Ryan Henry

TOMORROW at 3pm in LH 102!

After the talk, Chris will stick

around to meet with

students in

LH 102 from 4:30 to 5:00

1

Ryan Henry

Another upcoming talk!

Who: abhi shelat (University of Virginia)

When: 12:00—1:00pm on Thursday Oct 5

(One week from today!)

Where: Maurer 335

Title: TBA

Abstract: TBA

2

Ryan Henry

Tuesday’s lecture:

• More number theory

• Introduction to groups

Today’s lecture:

• Modular eth roots

• Discrete logarithms

3

Ryan Henry

Assignment 5 is due Tuesday, November 10!

(Please fill out Doodle poll for the optional lab!)

4

Ryan Henry

Recall: Groups

Defn: Let G be a non-empty set and let ‘•’ be a binary

operation acting on ordered pairs of elements from G.

The pair (G,•) is called a group if

1.

2.

3.

4.

Closure: ∀a,b∈G, a•b∈G

???

Associativity: ∀a,b,c∈G, (a•b)•c=a•(b•c)

???

Identity: ∃e∈G, ∀a∈G,

a•e=e•a=a

???

Inverses: ∀a∈G, ???

∃a-1∈G such that a•a-1=a-1•a=e

The group (G,•) is abelian (or commutative) if

5.

5

Commutative: ∀a,b∈G, ???

a•b=b•a

Note: We often refer to just the set G as the group if the operation is clear

Ryan Henry

Recall: Exponentiation in a group

▪ For n∈{1,2,3,…} we define an=a•a•a•••a

▪ For n=0, we define

an=e

n times

▪ For n∈{-1,-2,-3, …} we define an=(a-1)-n

Thm (law of exponents): Let (G,•) be a group and let

m,n∈ℤ. For each a∈G, am•an=am+n and (am)n=amn.

▪ Additive notation: If (G,+) is a group under addition,

then we write n•a≔a+a+⋯+a

n times

6

Ryan Henry

eth roots

Defn: Let (G,•) be a group and let a∈G. An eth root of a

in G is an element b∈G such that a≡b

??? e mod n.

Common notations include: b ≔

4 in (ℤ,•)

– 161/2≡??

e

a=

a1⁄e

=

ae

-1

8 in (ℤ,+)

– 161/2≡??

– 81/2≡??

5 in (℥17 ,⊡), where ⊡ is multiplication modulo 17

–

4

16≡??

2 in (ℝ,•)

(since 5•5=25≡8 mod 17)

Defn: An eth root of a modulo n is an eth root of a in

(℥n,⊡), where ⊡ denotes multiplication modulo n.

7

Ryan Henry

eth roots

Q: Do eth roots modulo n always exist?

A: No! (So when do they exist?)

(21/2 mod 11 does not exist, since 12≡1, 22≡4, 32≡9, 42≡5, 52≡3, 62≡3, 72≡5, 82≡9, 92≡4, 102≡1!)

Q: If an eth root of a modulo n exists, is it unique?

A: In general, no! (But when is it unique?)

(31/2≡5 or 6 mod 11, since 52=25≡3 mod 11 and 62=36≡ 3 mod 11)

Q: If an eth root of a modulo n exists, is it easy to compute?

A: Yes, provided we know the factorization of n!

8

Ryan Henry

eth roots modulo p

Suppose p>2 is prime and let a∈ℤp

Q: When does a unique solution for a1⁄e mod p exist?

A: If gcd(e,p-1)=1, then a1/e≡ad mod p where d≔e-1 mod p-1

If gcd(e,p-1)≠1, then a1/e may or may not exist;

if it does exist, then it is not unique!

Fact: If p>2 is prime, then the squaring function, which

maps each a∈G to a2 is a 2—to—1 function in ℥p.

9

Ryan Henry

Quadratic residues

Defn: An element a∈ℤn is a quadratic residue modulo n if

and only if it has a square root modulo n.

– At most half of elements in ℤn can be quadratic residues modulo n!

▪ The set of quadratic residues modulo n is denoted QRn.

– Fact: (QRn,⊡) is a group, where ⊡ is multiplication modulo n!

More generally, a is an eth residue modulo n if it has an eth

root modulo n.

10

Ryan Henry

Legendre symbols

Defn: If p>2 is prime, then (ap)≔a(p-1)⁄2 is called the Legendre

Symbol of a modulo p.

Q: What makes (ap) worthy of special consideration?

A: Fermat’s Little Theorem implies that (ap)2≡1 whenever a∈℥p!

(Note: (ap)∈{-1,0,1})

Thm (Euler’s Criterion): a∈℥p is a quadratic residue

modulo p if and only if (ap)=1; that is, if and only if (ap)≡1.

11

Ryan Henry

Jacobi Symbols

▪ The Legendre Symbol generalizes to composite moduli,

but the properties are slightly trickier:

– If (an)=1, then a is definitely not a quadratic residue modulo n

– If a is a quadratic residue modulo n, then (an) is definitely equal to 1

– However, if (an)=1, then a may or may not be a quadratic residue

modulo n!

▪ We will discuss Jacobi Symbols later on when we see the

Goldwasser—Micali cryptosystem

12

Ryan Henry

Computing square roots modulo n

Thm: If p is a prime such that p≡3 mod 4 and a is a

quadratic residue modulo p, then a1/2≡a(p+1)⁄4 mod p.

Proof: (a(p+1)⁄4)2 ≡a(p+1)⁄2

≡a1+(p-1)⁄2

≡a•a(p-1)⁄2

≡a

(law of exponents)

(rearranging)

☐

(Euler’s Criterion)

Q: Why do we insist on p≡3 mod 4?

A: If p≡1 mod 4, then (p+1)⁄4 is not an integer!

(If p≡1 mod 4, more complicated algorithm compute a1/2 in O(lg3 p) steps)

13

Ryan Henry

eth roots modulo n

Suppose n is composite and let a∈℥n

Q: When does a solution for a1⁄e mod n exist? When is it unique?

A: If gcd(e,φ(n))=1, then a1/e≡ad mod n where d≔e-1 mod φ(n)

If gcd(e,φ(n))≠1, then a1/e may or may not exist;

if it does exist, then it is not unique!

▪ Note: Suppose n=pq for distinct primes p and q. Then

knowledge of φ(n) is sufficient to determine n

▪ It appears hard to determine existence of a1/e when

factorization of n is not known…

14

Ryan Henry

Computing p and q from φ(pq)

▪ Goal: Given n=pq and φ(n), determine p and q.

φ(n)=(p-1)(q-1)=pq-p-q+1=(n+1)-p-q

⇒ (n+1)-φ(n)=p+q so that q=(n+1)-φ(n)-p

⇒ n=p(n+1-φ(n)-p)=-p2+(n+1φ(p))

⇒ p2-(n+1-φ(n))p+n=0

(defn of φ(n))

(rearranging)

(substitute into n=pq)

(rearranging)

▪ This is a quadratic equation in indeterminant p with

a=1

b=-(n+1-φ(n))

c=n

⇒ the quadratic formula yields p and q as the two roots!

15

Ryan Henry

The eth root problem

Defn: The eth root problem (aka the RSA problem) is: Given

(n,e,a) such that

1.

n=pq for distinct s-bit primes p and q,

3.

gcd(e,φ(n))=1,

2.

a∈℥n, and

compute a1/e mod n.

One possible solution: compute d≔e-1 mod φ(n) and output ad mod n

Fact: Compute d is equivalent to factoring n!

Q: Is solving eth root as hard as factoring?

A: Well…err, maybe? I dunno! (It may be possible to compute a1/e directly!)

16

Ryan Henry

Practice: Computing square roots modulo p

▪ Compute the square roots of 3 mod 139, if they exist.

Legendre Symbol: 3(139-1)/2≡138≡-1 mod 139

Roots do not exist!

▪ Compute the square roots of 5 mod 139, if they exist.

Legendre Symbol: 5(139-1)/2 = 1 mod 139

Roots exist!

Mod 4 congruence: 139 = 3 mod 4

Simple formula for computing roots!

“Positive” root: 5(139+1)/4 = 127 mod 139

“Negative” root: 139-127 = 12 mod 139

Ryan Henry

Practice: Computing eth roots modulo n

▪ Compute 511/11 mod 10 961 (Note: 10 961=113·97)

Compute φ(10 961): (113-1)(97-1)=10752

Relative primeness: gcd(11, 112·96) = 1

unique root exists!

Inverse mod 10752: 11-1≡1955 mod 10752

Compute root: 511955 = 6066 mod 10961

Ryan Henry

Logarithms

Defn: The logarithm of a to the base b is the number x

such that ???

a=bx

We denote that x is the logarithm of a to the base b by logba=x

???since 42=16

– log4 16=2,

– log5 125=???

3, since 53=125

– log2 128=7,

???since 27=128

– log2 16= 4,

???since 24=16

19

Ryan Henry

Recall: Order of a group element

Defn: The number of elements in a group (G,•) is called

its order. We write |G| to denote the order of (G,•).

Defn: Let (G,•) be a group and let a∈G. The smallest positive

integer i such that ai=e is called the order of a in (G,•). We

write |a| to denote the order of a∈G.

If |a|=|G|, then we call a a generator of (G,•).

20

Ryan Henry

Euler’s Theorem for finite groups

Thm: Let (G,•) be a group and let a∈G.

a i=a j in G if and only if i≡j mod |a|.

- Lagrange’s Theorem: Let (G,•) be a group with order |G|=N.

Then |a| divides N for all a∈G.

i

j

- Corollary: If i≡j mod |G|, then a =a in G.

Trick: To compute ai mod n, first reduce the exponent

(i.e., i) modulo |a|, or |G| if |a| is not known.

21

Ryan Henry

Cyclic groups

Defn: If (G,•) has one or more generators, then we call

it a cyclic group.

Thm: If |G| is prime, then (G,•) is cyclic.

- This follows directly from the generalization of Euler’s Theorem

on the last slide!

Note: If (G,•) is cyclic and |G| is given, then given any generator g∈G,

it is easy to select h∊G is easy. (How?)

22

- Choose r∊{0,1,…,|G|-1} and output h=gr

Ryan Henry

Discrete logarithms

Defn: Let G be a group with |G|=n and let g,h∈G. A discrete

logarithm (DL) of h to the base g in G is a number x∈ℤn

such that ???

h=gx in G.

Q: Does the DL of h to the base g always exist?

A: No! (So when does it exist?)

Q: If the DL of h to the base g exists, is it unique?

A: Sort of… If x1 and x2 are DLs of h to the base g, then x1≡x2 mod |g|

Thm: If (G,•) is a cyclic group of order n with g a

generator, then ∀h∈G, x=loggh exists and is unique in ℤn

23

- We therefore speak of the DL of h to the base g

Ryan Henry

The DL problem

Defn: Let (G,•) be a cyclic group of order n and let g be a

generator of G. Then the DL problem in (G,•) is:

Given (G,n,g,h) where g,h∈G with |g|=n, compute x=loggh

24

Ryan Henry

Intractable problems

▪ Intuitively, we call a problem intractable if no PPT

algorithm can solve a uniform random instance the

problem, except with negligible probability

▪ The factoring, eth root, and DL problems are all

believed to lead to “intractable” problems

– Attacker must be PPT in what parameter?

– Success probability must be negligible in what parameter?

25

▪ So far, all problems are defined in a particular finite

group

Ryan Henry

Group generating algorithm

Defn: A group generating algorithm G is a PPT algorithm

that, on input a security parameter 1s, outputs a finite

group (G,•) with s-bit prime order q and a generating

g∈G.

We write (G,•,q,g)←G(1s) to indicate that (G,•) is a group

with s-bit prime order q and generator g, sampled

from the output of G.

26

Ryan Henry

That’s all for today, folks!

27

Ryan Henry