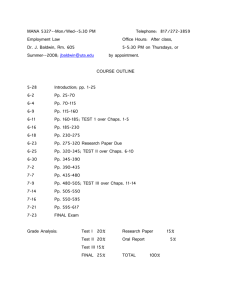

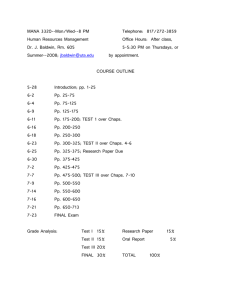

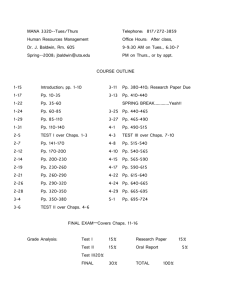

Handbook - Eng 456

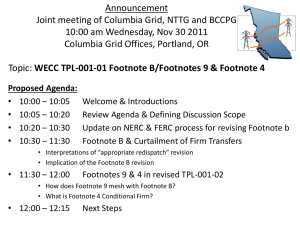

advertisement