Slide 1

advertisement

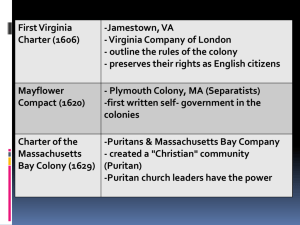

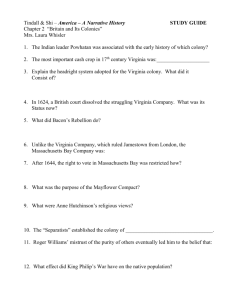

Jamestown King James I, in 1606, granted charter to a jointstock company headed by Richard Hakluyt. The Virginia Company of London, as it was known, divided the British claims in North America with a rival company, the Virginia Company of Plymouth. The London Company was made up of merchants and gentry from the west of England and from London, itself. On December 20, 1606, three ships left London with 144 passengers, under the command of Captain Christopher Newport. The ships briefly laid over at the Canary Islands and the Bahamas, before arriving in Virginia at Chesapeake Bay on April 26th with 104 survivors. Following the orders of the London Company, and after facing a brief conflict with the local Indians, the Powhatan, the ships landed up the newly-named James River and encamped at what became Jamestown on May 13, 1607. After much turmoil and the near elimination of the colony, by the late 1610s the colony was on fairly solid footing. Under new Governor Edwin Sandys, the London Company created a new policy for land distribution and to entice more settlers. The headright system promised that every new company shareholder who settled in Virginia would get 50 acres of land for himself and 50 acres for each “family member” he brought over, including servants. Further to entice settlement, the company a new constitution for the colony, granting settlers the “Rights of Englishmen.” In July 1619, Virginia created the House of Burgesses, the first legislative assembly in America. Its twenty-two members represented their local settlements and governed along with a Governor and executive council. Two other events in 1619 further expanded the colony: (1) more women arrived as the company sponsored the sale of women for wives – 90 women were bought for the princely sum of 125 pounds of tobacco – creating a better gender balance in the colony; (2) the first Africans arrived – they came on a Dutch trade ship, but were indentured servants, not slaves. An indenture is a contract. So, in return for the master’s paying their passage to the New World, an indentured servant contracts to work for a specific term, usually seven years. During that time the servant has no rights to property. Upon completion of the term, the servant is free to do whatever he or she wishes and under Virginia law would receive a headright of 50 acres. New England Colonies: Plymouth In 1541, John Calvin created his church in Geneva, Switzerland. Calvin attracted “religious dissenters” from all over Western Europe, including John Knox who took Calvinism to Scotland creating the Presbyterian Church. Several Englishmen also went to Geneva, learned Calvin’s ideas, and brought them back to England. In 1564, they coin the term “Puritan,” meaning a person who wishes to purify the Church of England of its Catholic rituals. Specifically, they wished to reform the church organization and refocus church doctrine away from “works” and toward the belief that salvation comes by God’s grace alone. Organizationally, they wanted the church organized from the bottom up. They wanted the congregation to be the primary force in decisions for the church. For this reason, in America the descendant of Puritanism is called Congregationalism. During the reign of Elizabeth I, Puritans were not totally free to worship as they chose, but neither were they persecuted. King James I was less hospitable, however, and the Puritans split into two groups: the Puritans (who wanted to stay in England and work within the system to reform it) and the Separatists (who said enough is enough, England is lost beyond redemption; let’s find somewhere else to live). So they left the town of Scrooby in England and moved to the town of Leyden in the Netherlands in 1609. After years in Holland, the Scrooby Separatists feared the moral decay of their community amid the permissive Dutch culture. In 1619, they contracted with the London Company to settle in Virginia and the crown ensured that they could practice their religion freely there. With financial help from a group of merchant adventurers, they set up their voyage. St. Wilfrid's Church in Scrooby In July 1620, 35 of the 238 members of the Leyden congregation, led by William Bradford, sailed to Southampton to meet more Separatists and the 180ton Mayflower. After two false starts, including a forced docking at Plymouth, the 102 saints and strangers set sail for Virginia. The Separatists called themselves the Saints – as in visible saints, those elected to heaven; the others, a majority of the passengers, they called strangers and included Anglicans and at least one Roman Catholic. Two months later, 103 landed along Cape Cod – two babies were born and one youth died en route – some five hundred miles off course. Since they could not be governed under the London Company’s charter, being so far north, the men aboard agreed to write up a new contract for the settlement. Called the Mayflower Compact, it represented the first example of self-government in the New World. The settlers agreed to create a system of laws, to elect leaders, and to obey those laws and leaders. “The Mayflower Compact”: IN THE name of God, Amen. We whose names are underwritten, the loyal subjects of our dread sovereign Lord, King James, by the grace of God, of Great Britain, France and Ireland king, defender of the faith, etc., having undertaken, for the glory of God, and advancement of the Christian faith, and honor of our king and country, a voyage to plant the first colony in the Northern parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually in the presence of God, and one of another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil body politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute, and frame such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions, and offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the colony, unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunder subscribed our names at Cape-Cod the 11 of November, in the year of the reign of our sovereign lord, King James, of England, France, and Ireland the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth. Anno Domine 1620. Massachusetts Bay Colony 1n 1623, with Plymouth established and growing, a group of settlers traveled north to Cape Ann looking for fishing grounds and establishing the settlement of Gloucester. Within three years, a number of fishing villages dotted Cape Ann. In 1628, in search of more capital for better equipment and to generate more settlement, the sponsors of these settlements formed a joint-stock company, the Massachusetts Bay Company. They petitioned the king for a charter to lands between the southernmost point of the Charles River and the Merrimac River. The charter granted the “freemen” of the company the right to select all officers, admit newcomers to freemanship, to make laws and administer those laws through a general court. The company’s primary goal was profit and economic opportunity, but conditions for the Puritans in England had deteriorated under Charles I, James I brother and an ardent Catholic. He had run into conflict with the Presbyterians in his native Scotland and he had no intention of tolerating the English Calvinists. During the 1630s, some 80,000 people left England for the New World. It was known as the Great Migration. Of those, about 20,000 came to Massachusetts Bay. In 1629, a group of well-placed and wealthy Puritan landholders pledged to go to the New World with their families and their fortunes. Although partly a business venture, the colony would be, as John Winthrop called it, a “Wilderness Zion,” a place of religious refuge for persecuted Puritans. In March 1630, led by Governor Winthrop, 400 Puritans left for the New World. They landed at Salem, June 12, 1630. 600 more Puritan settlers soon followed, ultimately to create a new community at the mouth of the Charles River to establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony. While aboard the Arbella, Winthrop set out his plan for the colony in a sermon, titled “A Model of Christian Charity” based on the line from the Gospel of Matthew 5:14 “You are the light of the world. A city set on a hill cannot be hid.” “A Model of Christian Charity” Now the only way to avoid this shipwreck and to provide for our posterity is to follow the counsel of Micah, to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God, for this end, we must be knit together in this work as one man, we must entertain each other in brotherly affection, we must be willing to abridge ourselves of our superfluities, for the supply of others necessities, we must uphold a familiar commerce together in all meekness, gentleness, patience and liberality, we must delight in each other, make others’ conditions our own: rejoice together, mourn together, labor, and suffer together; always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work, our community as members of the same body, so shall we keep the unity of the spirit in the bond of peace, the Lord will be our God and delight to dwell among us, as his own people and will command a blessing upon us in all our ways, so that we shall see much more of his wisdom, power, goodness, and truth than formerly we have been acquainted with, we shall find that the God of Israel is among us, when ten of us shall be able to resist a thousand of our enemies, when he shall make us a praise and glory, that men shall say of succeeding plantations: the lord make it like that of New England. For we must consider that we shall be as a City upon a Hill, the eyes of all people are upon us; so that if we shall deal falsely with our god in this work we have undertaken and so cause him to withdraw his present help from us, we shall be made a story and a byword through the world, we shall open the mouths of enemies to speak evil of the ways of god and all professors for God’s sake; we shall shame the faces of many of gods worthy servants, and cause their prayers to be turned into curses upon us until we be consumed out of the good land whether we are going: And to shut up this discourse with that exhortation of Moses that faithful servant of the Lord in his last farewell to Israel (Deut. 30). Beloved there is now set before us life, and good, death and evil in that we are commanded this day to love the Lord our God, and to love one another to walk in his ways and to keep his commandments and his ordinance, and his laws, and the articles of our covenant with him that we may live and be multiplied, and that the Lord our God may bless us in the land whether we go to possess it: But if our hearts shall turn away so that we will not obey, but shall be seduced and worship other Gods, our pleasures, and profits, and serve them, it is propounded unto us this day, we shall surely perish out of the good land whether we pass over this vast sea to possess it; . . . Therefore let us choose life, that we, and our seed, may live; by obeying his voice, and cleaving to him, for he is our life, and our prosperity. Q1. What does Winthrop mean by the term “City upon a Hill”? Q2. According to Winthrop, how can this city be achieved and what will prove its achievement? Q3. Does the Massachusetts Bay Colony live up to the Puritans’ expectations of such a city? Q4. Explain: “abridge ourselves of our superfluities,” “succeeding plantations,” “covenant”. Administration of Massachusetts Bay Colony The Massachusetts Bay charter was a commercial agreement among stockholders, but once it was taken to New England it became a constitutional blueprint for the Puritan colonies. The administration of the colonies was to be built around the “freemen,” or company shareholders residing in the colony. The freemen were to meet four times a year in a “great and generall Court,” to make laws necessary to govern the colony. Freemen also were to elect administrative officials who would run the day-to-day business of the colony. The administration would consist of “one Governor, one Deputy Governor, and eighteene Assistants of the same company.” The administrators would meet monthly. The problem with the charter was that government power was concentrated in the hands of too few men. The General Court included only the “freemen.” Only shareholders in the company could be included among the legislators. In 1631, a conflict grew out of this issue when some recently arrived male settlers wanted to sit in the General Court. In order to avoid a major fracas, Governor Winthrop agreed to expand the definition of “freeman.” All church-members were allowed the right to vote and sit in the General Council. While this provided an increased franchise and participation, it is important to note that church membership was restricted to men only and based on proof of one’s election--that is, being among those whom God has predestined as being saved. Winthrop believed it would be best for the new colony if he consolidated control of the administration around him. To get away with this, he hid the charter from the citizens. In 1632, a crisis flared up when Winthrop levied a tax on the citizens of Watertown. They raised a stink because they had not had a say in the levying of the tax. To appease the Watertown Protestors, Winthrop decided to reform the charter (actually to restore it to its original intent) and allow “freemen” to vote for the governor and deputy governor, as well as the Assistants. This settled the matter for two years, but when no compromise on taxation could be worked out, colonists demanded to see the charter. In it, they saw that it was the General Court, the “freemen” not the governor alone, who had the power to tax. Winthrop responded, claiming that the population had grown too large for all to participate in governing it. But when the General Court met it rejected Winthrop’s claim and created a representative government, with two or three deputies representing each town, depending on its size. It also voted out Winthrop as Governor. But within three years, he was re-elected. The last stage in the development of Massachusetts Bay’s government came in 1644, when the General Court split into a House of Assistants (like the House of Lords) and House of Deputies (like the House of Commons). The bicameral assembly was the first of its kind in America. All laws required support from a majority of delegates in both houses before enacted. New Netherland In 1609, the Dutch East India Company had hired Henry Hudson to discover the “Northwest Passage.” Hudson sailed the coast of North America and located the river that now bears his name. He sailed as far up-river as he could but was stopped by rapids at what is now Albany, New York. Not able to go farther, he met with the local Mohican Indians and negotiated a contract for the Mohicans to provide furs to the Dutch. They sealed the deal with a few kegs of brandy. In 1614, the Dutch established trading posts on Manhattan Island at the mouth of the river and Fort Orange at a site below the rapids. Ten years later, the Dutch West India Co. established a settlement at what is now Governor’s Island. In 1626, Peter Minuit bought Manhattan Island from the Indians and moved the settlement there, calling it New Amsterdam. The colony spread west to the Delaware, east to the Connecticut River, and north to the Mohawk River but remained only thinly populated because its focus was on furs. The company did encourage settlement. It established the patroon system, modeled after the European manorial and the French seigneurial systems. A stockholder governed a patroonship, a large estate on the Hudson River, if he peopled it with 50 adults within four years, and established herds, barns, mills, and any other necessities for farming. The tenants would treat him as “lord of the manor,” paying him rent, using his mill, and submitting to his authority. The patroon system did little to entice settlers, however, because too much open land was available and few Dutchmen wanted to volunteer for serfdom. The English Civil War raged for most of the decade of the 1640s and Puritans took control of the English government in 1646. In 1649, they executed the king. The beheading ushered in eleven years of Commonwealth. In 1660, the Commonwealth collapsed and the people restored the Stuarts to the thrown. The Restoration of the crown in England, in the person of Charles II, led to the official recognition of Rhode Island and Connecticut. It also led to new expansion into the new world. The Dutch expanded their territories while the British were engaged in Civil War. The British Crown fretted over the Dutch presence dividing the English colonies. Charles II decided to push the Dutch out. The rivalry resulted in war in 1664 when an English expedition reached New Amsterdam. Dutch Governor Peter Stuyvesant vowed that the Dutch would fight. But without the supplies, weapons, or the will to withstand the English, the Dutch surrendered without a shot being fired. King Charles granted the lands to his brother James, the Duke of York and the colony became New York. Some of the Dutch returned to Holland, but most of them stayed. With so many non-English in the colony, representative government was slow to evolve. Still, inhabitants were given certain guarantees: (1) local property holders could elect a constable and eight overseers to supervise town government; (2) the towns would be placed under justices of the peace named by the governor; (3) these justices aid the governor in making laws; and (4) because of the diverse polity--made up of Frenchmen, Swedes and Finns, as well as Dutch and English--there was complete religious toleration. In 1682, a legislature was established and wrote the Charter of Liberties and Privileges, guaranteeing colonists the “Rights of Englishmen.” But, in 1685, when James became King James II he turned New York into a royal colony, the charter was denied and the legislature dissolved. Because the bulk of the population was comprised of newcomers, the social structure of the English colonies, at first glance, looked like that of the mother country. The social hierarchy that symbolized the class system in England was transplanted with the settlers, as “lesser” almost always deferred to the “betters.” A free-holder always deferred to a planter and a servant deferred to a free-holder. One fundamental difference did exist, however. The colonies were characterized by social mobility rather than a fixed class system. Many of the first landowners of Virginia had died or returned to England. The next wave of settlers was comprised of men of lesser means, having only one or two servants or no servants at all. They succeeded or failed by their own labors. The turmoil evinced by Bacon’s Rebellion or the others of which we will speak resulted from the fact that those who had made their own success refused to be governed by cliques or entrenched elites. Political-Economy after the Restoration One of the first acts of King Charles II upon the Stuart Restoration was to punish those responsible for his father’s beheading. With their own necks on the line, two of the late king’s judges fled to New England. Charles II ordered their arrest and return, but colonial officials enabled them to escape to the wilderness of Connecticut. Irate at the colonials, Charles II began to take steps that would fundamentally alter the relationship between Britain and New England, and Massachusetts in particular. He ordered that the colonials take a new oath of allegiance to him, that the crown review all laws and legal proceedings of the Massachusetts General Court, and that members of the Church of England have free and equal rights of worship, as well as political rights in the colony. The leaders of the Massachusetts colony ignored the King’s demand and delayed its implementation. The colony won a reprieve as the King’s attention was diverted by a war with the Dutch and by the rebuilding after the Great Fire of London in 1666. But Massachusetts could not avoid the King’s authority forever. With complete political control over the colonies out of its reach, the crown focused on controlling the colonial economy. The last half of the seventeenth century witnessed significant expansion of the colonial economy. Britons saw the economic value of creating colonies. By the mid-seventeenth century, the idea had developed into a full-fledged economic theorem, called mercantilism. Wealth = power Gain wealth through trade/commerce Improve “balance of trade” Increase exports and decrease imports Create colonies Control the colonial economy Navigation Acts The English believed that the colonies should provide England with raw resources--furs, lumber, and fish--as well as a market for English manufactured goods. Beginning in 1651, Parliament passed laws to ensure this symbiotic relationship between the colonies and the mother country, implementing a regulatory system under the Navigation Acts of 1651. Charles II, upon restoration in 1660, expanded the Navigation Acts. In 1704, 1705, 1721, and 1729, Parliament modified the list bringing more goods under its control. The crown also established a new bureaucracy to implement the policy. It created the Lords of Trade and Plantations in 1675. The committee was ineffective, for the most part, because of understaffing and distance. Colonials frequently flouted the laws, smuggling goods from the West Indian holdings of Spain and France. Then it was overwhelmed by the tensions that led to the Glorious Revolution. But it did establish a framework for British control that would follow during the reign of King William. Between 1675 and 1689, a power struggle developed between the colonies and mother country, as well as between the powerful and powerless within the colonies. Five rebellions occurred, involving each of the four colonial regions. Each of the rebellions had causes particular to their colony, but they also reflected a struggle to answer the question: “Who’s in charge.” A similar tension reigned in Britain. James II, an avowed Catholic, began to exploit royal prerogatives to enhance Catholic influence in government. The king’s excesses caused England’s latent political factions to develop into the more clearly defined Court Party (King’s Court; a.k.a Tories) and Country Party (Parliament; a.k.a. Whigs). The Whigs, fearing absolute monarchy, rebelled. Within six weeks, James fled to France and the bloodless Glorious Revolution of 1688 ended. The Glorious Revolution occurred as Europe, and particularly Britain, was experiencing an important change in world-view. Known as the “English Enlightenment,” it reflected the advance of the scientific revolution that had been ongoing for more than a century. The scientific revolution bred new approaches to other elements of life, including politics. The most important political thinker of the English Enlightenment is John Locke (1632-1704). The eldest son of a respectable Somersetshire Puritan family, Locke’s formative years were surrounded by religious and political tension. He was strongly influenced by the events of the English Civil War and Interregnum. Freedom of thought and to a lesser degree action became the foundation on which he built his philosophy. Two works by Locke stand out: An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690); and Two Treatises of Government (1690). First, and paramount, in Locke’s view of political society is the idea that mankind at the beginning of time were free and endowed with certain natural rights: life, liberty, and property. It was in a complete state of nature, free from obligation, free to do whatever they chose to do. While this state of nature had its advantages, it was not satisfactory for the maintenance of a sustained existence. Nature is dangerous because the strong can devour the weak. One’s life, liberty, or property were constantly at risk. Locke’s predecessor, Thomas Hobbes, described life in a state of nature as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” To survive, men joined together in the spirit of community to protect their rights. They left a state of nature and created government. Man kept his freedoms--the right freely to pursue property, the right to mobility, and the right to life. But his freedoms were not absolute. By joining society, man had to conform to the will of that society’s laws. This is, in a sense, a contract between individual man and society: a social contract. To this point, Locke is not radically different from his predecessor Hobbes. Where the two part company is over what happens if the contract is broken not by man, but by government. Locke’s answer is that in such times man has a right to revolt against the government. The revolution is a conservative one, however: to restore the community to the original terms of the contract. Locke’s writing is a justification of the Glorious Revolution of 1688. King William’s War, (1689-1697): A tie, the French take English territories of Newfoundland and Hudson Bay, and England gets Gibraltar at the entrance of the Mediterranean Sea. Queen Anne’s War, (1701-13): Colonists from Charleston destroy St. Augustine. New Englanders attack Quebec, but fail to take it. England regains Hudson Bay, Acadia, and Newfoundland. King George’s War, (1744-48): As a world war, it is a tie. In North America, England took a major French fort, Louisburg, showing her naval dominance and paving the way for an assault on Quebec. The wars with France left the British government deep in debt. The debt and an economic collapse forced Prime Minister Robert Walpole to find ways to cut spending. In 1723, he created the policy called Salutary Neglect. It relaxed enforcement of the Navigation Acts and allowed the colonial economy to run along essentially unregulated. During the brief time of unsupervised growth, the colonies experienced a Great Awakening and the Enlightenment. In 1754, with the colonies on the brink of war, Ben Franklin devised the Albany Plan of Union to enable the colonies to protect themselves. Delegates met in Albany, New York, to form an alliance with the Iroquois against the French and their Huron allies; and potentially to create a governing council for all the colonies. It was not an independence movement; it intended only to bring the colonies closer together. Some colonies thought it was a good idea, but a majority did not want to give up any power over their own affairs to another layer of government. Salutary Neglect ended with the French and Indian War (1754-1763) when, Britain started controlling the colonies by imposing new economic regulations, taxes, and restrictions on movement. When it was so abruptly ended, it caused a groundswell of opposition that would eventually grow into an American Independence movement. The land between the Appalachians and the Mississippi posed an opportunity and a problem for Britain. Colonials wanted to flood the territory, but each new incursion resulted in conflict with the Indians. So King George III banned colonists from entering the region. The Proclamation of 1763 banned all settlement west of the continental divide in the Appalachians. A series of new taxes and enforcement procedures further demonstrated that the British were going to change the rules on the colonies and further alienated colonists: Sugar Act, 1764; (a.k.a. Revenue Act); Currency Act, 1764; and the Stamp Act, 1765– which imposed a direct tax on printed matter and documents. Many colonial leaders, hit hard by the tax, sought a way to challenge Parliament’s authority. They latched on to political theories offered by British Whigs, in the tradition of John Locke. Among the most important opponents of the tax was James Otis. By no means a radical, nor wanting colonial independence, Otis had developed an argument against the taxes in 1764, in The Rights of the British Colonists Asserted and Proved. “The colonists will have an equitable right . . . to be represented in Parliament, or to have some new subordinate legislature among themselves. It would be best if they had both. . . . Besides the equity of an American representation in Parliament, a thousand advantages would result. . . . It would be the most effectual means of giving those of both countries a thorough knowledge of each others interests.” James Otis The key issue for the colonists was representation and governing with the consent of the people. Otis offered an argument in favor of “direct representation.” Delegates from each community would meet in an assembly, acting a agents for their constituents; they would debate, wheel-and-deal, and compromise their way to a policy satisfactory to a majority. Britain responded, arguing a concept called “virtual representation.” As Britain progressed into a more modern nation-state, regional differences diminished and were replaced by general or national interests. Thus, representation in Parliament gradually changed from local to national. Members of the House of Commons represented the interests not just of their particular constituents, but of all of the “commons.” The House of Lords, represented the interests of the gentry. Several issues made virtual representation inadequate in the colonies: (1) a more fluid social organization than Britain; (2) a more diverse population than Britain; and (3) the fundamentally different interests involved in governing a frontier settlement from governing Britain. Of course sheer distant made direct representation inadequate, as well. “It is inseparably essential to the freedom of the people, and the undoubted rights of Englishmen, that no taxes should be imposed on them, but with their own consent, given personally, or by their representatives.” Patrick Henry In May 1765, Virginia led the attack on the Stamp Act. In the House of Burgesses, Patrick Henry pushed five resolutions through despite catcalls of “treason” by his opponents. The most significant were that colonials enjoyed all the “Rights of Englishmen” and that Virginians were exempt from any tax that did not derive from their own assembly. In June 1765, Massachusetts sent invitations to each of the colonial assemblies to meet in New York to discuss a unified colonial response to the Stamp Act. Nine colonial delegations met in the Stamp Act Congress in New York, beginning on October 7th. Georgia and New Hampshire could not afford to send delegates; Virginia and North Carolina did not send delegates because their assemblies were out of session. The Congress deliberated for three weeks and issued the “Declaration of Rights and Grievances and a petition to King George III for relief. That the inhabitants of the English Colonies in North America, by the immutable laws of nature, the principles of the English constitution, and the several charters or compacts, have the following Rights: 1. That they are entitled to life, liberty, and property. 2. That [those] who first settled these colonies, were . . . entitled to all the rights, liberties, and immunities of free and natural born subjects within the realm of England. 3. That by such emigration they by no means forfeited, surrendered, or lost any of those rights. * * * 5. That the respective colonies are entitled to the common law of England, and to the great and inestimable privilege of being tried by their peers. 6. That they are entitled to the benefit of such of the English statutes [that] they have, by experience, respectively found to be applicable to their several local and other circumstances. 7. That these, his majesty's colonies, are likewise entitled to all the immunities and privileges granted and confirmed to them by royal charters, or secured by their several codes of provincial laws. 8. That they have a right peaceably to assemble, consider of their grievances, and petition the King. 9. That the keeping a Standing army in these colonies, in times of peace, without the consent of the legislature of that colony in which such army is kept, is against law. 10. It is indispensably necessary to good government . . . that the constituent branches of the legislature be independent of each other; that, therefore, the exercise of legislative power in several colonies, by a council appointed . . . by the crown is unconstitutional. . . and destructive to the freedom of American legislation. The key point, beyond basic legal rights, in the Declaration is Part 4. wherein the Congress discusses representation. 4. That the foundation of English liberty, and of all free government, is a right in the people to participate in their legislative council: and as the English colonists are not represented, and from their local and other circumstances, cannot properly be represented in the British parliament, they are entitled to a free and exclusive power of legislation in their several provincial legislatures, where their right of representation can alone be preserved, in all cases of taxation and internal polity, subject only to the negative of their sovereign, in such manner as has been heretofore used and accustomed. But, from the necessity of the case, and a regard to the mutual interest of both countries, we cheerfully consent to the operation of such acts of the British parliament, as are bona fide restrained to the regulation of our external commerce, for the purpose of securing the commercial advantages of the whole empire to the mother country, and the commercial benefits of its respective members excluding every idea of taxation, internal or external, for raising a revenue on the subjects in America without their consent. The Declaration warned of the actions colonies intended to take to make Parliament back down to “restore us to that state in which both countries found happiness and prosperity, we have for the present only resolved to pursue the following peaceable measures: 1. To enter into a non-importation, non-consumption, and non-exportation agreement or association. 2. To prepare an address to the people of Great Britain, and a memorial to the inhabitants of British America, and 3. To prepare a loyal address to his Majesty, agreeable to resolutions already entered into.” “Parliament has a right to bind the colonies in all cases whatsoever.” Declaratory Act, 1766 The actions of the colonists (especially the boycotts), lobbying by Franklin in Parliament, and support from Whigs in Parliament (notably Edmund Burke) finally combined to force Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act.. The repeal obviously was a victory for the colonists, but Parliament moved quickly to reassert its authority. Parliament passed the Declaratory Act, which asserted Parliament’s right to enact taxes and any other laws on the colonies. A year later, Parliament enacted a new tax: The Revenue Act of 1767, better known as the Townshend Duties, placing tariffs on glass, lead, paper, paint, and tea. The law also set up a Board of Customs in Boston to collect the tax; and it recognized the vice-admiralty courts as having jurisdiction over the law—this removed suits involving the tariff from colonial courts and colonial juries. Additionally, Townshend suspended all laws enacted by the New York Assembly until New Yorkers began obeying the Quartering Act of 1765. That law required colonials to provide provisions and housing to British troops stationed there. It hit New York hardest because New York was the headquarters of the British force in the colonies. The new taxes caused opponents of the laws to split over tactics. The moderate view was represented by John Dickinson in his Letters of a Pennsylvania Farmer. Dickinson was a wealthy planter and a true patriot of the colonies, but he feared British power and did not want to make matters worse by resorting to mobism. He repeated the arguments of the Declaration of Rights in a clearer and more plain-spoken manner. But he stopped short of advocating violence. “The cause of Liberty,” he exclaimed, “is a cause of too much dignity to be sullied by turbulence and tumult.” Outraged by the new taxes, many colonials again called for boycotts. Among the most aggressive were the Sons of Liberty in Massachusetts, led by Samuel Adams. A young Harvard graduate, Adams inherited his family’s brewery and soon ran it into the ground. Described as the “Puritan type . . . poor but incorruptible,” he found his calling in rebel rousing. In 1768, in the Massachusetts Assembly, Adams and James Otis wrote the Massachusetts Circular Letter (open letter) attacking Parliament’s taxing and calling on other colonies to join Massachusetts in opposition. The letter drew the attention of the Colonial Secretary and made Adams and Otis marked men. Otis would be beaten by a crowd of British loyalists and Adams would eventually be charged with treason. Meanwhile, Francis Bernard, Royal Governor of Massachusetts dissolved the assembly. But soon the answers to the letter started arriving: the colonies supported Massachusetts. The Boston Tea Party On December 16th, 1773, the issue came to a head. Three ships carrying a new cargo of tea were to land at Griffin’s Wharf. That night, Adams’ Sons of Liberty met at the South Meeting House to organize their protest. Some dressed up as Mohawk Indians, others as women, and they sneaked through the dark down Congress Street to the wharf. They boarded the ships and tossed 45 tons of tea, valued at £10,000 into the harbor. The tea washed up on the shores of Boston Harbor for weeks afterward. The British response was quick and severe. In March, Parliament enacted a series of laws, known collectively as the Coercive Acts because they meant to coerce better behavior from Massachusetts, or as the Intolerable Acts because the colonials found they could not tolerate them. 1. Boston Port Act: closed the port of Boston to all traffic and trade. 2. Act for the Impartial Administration of Justice: moved all trials to Admiralty Courts in Halifax. 3. Massachusetts Government Act: the Royal Governor appoints the colonial council and law enforcement officers. 4. Quartering Act of 1774, which expanded the requirement to provide room and board for British soldiers, including in private homes, if necessary. The Intolerable Acts began a tumbling snowball that within two years led to American independence. On September 5, 1774, delegates from each of the Thirteen Colonies, except Georgia, met a Carpenter Hall in the First Continental Congress. Canadian and West Indian delegations were invited, but did not attend. Among the delegates were John and Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, George Washington, John Dickinson, as well as Edmund Rutledge of South Carolina, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, and John Jay of New York. The Congress debated, but rejected a plan that would have created the Continental Association, similar to Franklin’s Plan of Union. It approved an embargo on all British goods. And it accepted an idea from Thomas Jefferson’s Summary View of the Rights of British America that only the King, not Parliament, had power to govern the colonies. Known as the Dominion Theory, it intended to take Parliament out of the mix and plead its case directly to the crown. It was a potentially dangerous argument, because if the king backed Parliament, then the colonies would have little room for further maneuvering. The Congress adjourned in October with orders to meet again in May 1775. Battle of Lexington and Concord Old North Bridge Lexington Green The Road Back Colonials were split in their response to Lexington and Concord. Patriots organized militia, while loyalists asked for a cessation of conflict. Quaker Pennsylvania divided between pacifists and fighters, while the rest of the colony divided into patriots, led by Franklin, and loyalists, led by John Dickinson. In the Chesapeake, Maryland opposed revolution, while Virginia (and especially Patrick Henry) supported it. A month before Lexington, Henry urged the House of Burgesses to organize a militia, giving his oft-quoted speech, “Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!” Loyalism was stronger in the Lower South, particularly in the back-country among the Scots-Irish who distrusted the Low Country planters. But a strong patriot contingent also existed in the Carolinas, as well as Georgia. On May 20th, Mecklenburg County issued four resolutions and declared its independence: “We do hereby declare ourselves a free and independent people; are, and of right ought to be a sovereign and self-governing association, under the control of no power, other than that of our God and . . . Congress: To the maintenance of which Independence we solemnly pledge to each other our mutual cooperation, our Lives, our Fortunes, and our most Sacred Honor.” “There is something charming to me in the conduct of Washington: a gentleman of one of the first fortunes upon the continent, leaving his delicious retirement, his family and friends, sacrificing his ease and hazarding all in the cause of his country.” John Adams Second Continental Congress: Meeting, beginning in May 1775, after Lexington and Concord, it was the first that included delegates from all of the colonies. The delegates were split. There was strong sentiment to avoid further conflict, but preparedness was important. The Congress named George Washington as Commander-in-Chief of the proposed Continental Army. John Adams: Boston lawyer, led Independence Movement at Second Continental Congress. Although short in stature, he had a strong mind, a huge ego, and an ability to drive his colleagues crazy with sheer force of character. He was ambassador to Britain during the Confederation era, was first Vice-POTUS and second POTUS. Thomas Jefferson: Main author of the Declaration of Independence, inventor, writer, and musician. He was ambassador to France during the Confederation era, the first Secretary of State, second Vice-POTUS, and third POTUS. Fiercely political, he led the DemocraticRepublican Party. “I HAVE never met with a man, either in England or America, who hath not confessed his opinion, that a separation between the countries would take place one time or other: And there is no instance in which we have shown less judgment, than in endeavoring to describe, what we call, the ripeness or fitness of the continent for independence.” Tom Paine Common Sense (1776): Pamphlet written by radical English Quaker Tom Paine and published in Philadelphia in January 1776. It argued that it made no sense for the colonies to stay part of England. Its fiery language and clear reasoning helped convince the large segment of undecided to join the independence movement Declaration of Independence: Founding document of the U.S. signed on July 4, 1776. It was written by committee (Ben Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston) with most of the work done by Jefferson: the document is in four parts: 1. a preamble, offering an introduction as to the purpose of the document 2. explanation of natural rights, based on Locke's “social contract:” life, liberty, pursuit of happiness 3. presentation of the list of complaints against King George III 4. statement of intent, i.e. the actual declaration that the colonies are sovereign and independent The War of Independence raged for nearly seven years until victories at Yorktown and an alliance with France forced the British to sue for peace. The Peace of Paris (September 1783) ended the War of Independence. Negotiated by Ben Franklin, John Jay, and Henry Laurens, it gave the U.S. control of all the land east of the Mississippi River, north of Florida, and south of British Canada. Articles of Confederation With independence, it became necessary for each state to reconstitute its government. Given their unhappiness with the monarchical experience, the states universally chose a republican form and a written constitution. Debates at the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention in 1779-80 offer an eloquent statement of the goals and beliefs: “The body politic is formed by a voluntary association of individuals; it is a social compact, by which the whole people covenants with each citizen, and each with the whole people that all shall be governed by certain laws for the common good.” Each state had an elected governor and a senate, and most wrote bills of rights to provide basic protections to the people. The rights included: freedom of speech, the right to petition, trial by jury , and freedom from self-incrimination. In 1776, John Dickinson drafted a national constitution, called the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union. It was adopted by the Continental Congress in 1777, but ratification by the states took until 1781. It created a “diplomatic congress of autonomous states.” Ratification of the Articles was delayed by the debate over control of western lands. The Confederation government also successfully created government departments to carry out its most essential duties: Foreign Affairs; War; and Finance, as well as the Post Office. Foreign Affairs was headed by New Yorkers Robert Livingston and then John Jay, but was ineffectual. The War Department was headed by Henry Knox; it was lucky we were at peace because without money for troops we would not have been able to put up much of a fight. Finance was headed by Robert Morris, the Philadelphia merchant who had almost singlehandedly financed the Revolution. Morris created the Bank of North America, a privatelyowned, part government-financed institution to hold federal deposits (if there were any) and to facilitate borrowing (which there was a lot of). An otherwise decentralized banking system, vested local interests, and general distrust of centralized authority stymied Morris’ attempts to organize the national government’s economic affairs. In frustration, Morris and others, including Alexander Hamilton threatened a coup d’etat, if the states did not give more power to the national government. When Hamilton solicited George Washington’s support for the coup, however, the Newburgh Conspiracy was ended. Washington thought the idea too risky and entirely too dishonorable. Forgive me, Gentlemen, but I have grown blind as well as gray in service of my country -- Gen. George Washington to the Newburgh Conspirators Weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation Weaknesses Effect Congress had no power to levy or collect taxes The national government is dependent upon the states and is always short of money Congress had no power to regulate interstate or foreign trade Economic quarrels broke out among the states. It was difficult to arrange a coherent foreign trade policy Congress had no power to enforce its laws The national government is dependent upon the states to enforce laws Approval of nine states was needed to enact laws It was difficult to enact laws, especially given the absence of quorum Amendments to the Articles required unanimous vote Amending the Articles was impossible given Rhode Island’s non-participation The national government had no executive branch There was no way to coordinate the work of the government There was no national judiciary or court system The national government had no way of settling disputes among the states Given the obvious flaws in the Articles, several leaders from Maryland and Virginia met at Mount Vernon to discuss how to fix them, as well as to speculate on some potential business ventures that might bring more development to the nation. They suggested a convention of the states to meet in Annapolis, Maryland (U.S. capital) at which delegates would discuss reform. The meeting was held in September 1786, but so few states sent delegates that no debate occurred. They decided to try again in Philadelphia in the new year. The failure of the Annapolis Convention further demonstrates the weakness of the federal government. Shays’ Rebellion: Over the winter of 178687, farmers in western Massachusetts found themselves unable to pay their mortgages because of a poor harvest and a tax increase. Armed (and usually drunk), the farmers rose up in protest. Led by Daniel Shays, they took over courts to block judgments against their farms. Some began a march on Boston and rumors abounded that they were on a rampage and heading to Annapolis to overthrow the government. The government was thrown into a panic. The inability of the federal government to stop the uprising showed the weakness of the Articles and caused a national emergency. “Miracle at Philadelphia”: Constitutional Convention of 1787—after years of ineffective government, the country’s leaders met in Philadelphia to create a new plan of government. George Washington presided and Benjamin Franklin gave his authority to the project. Jefferson and Adams were not there. In the summer heat, with the windows nailed shut and the doors locked because of armed protesters marching outside, the delegates debated, disagreed, compromised, and drafted the Constitution of the United States, the oldest written constitution still in use. Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804): In the Revolution, he distinguished himself as a brave soldier and was aide-de-camp to George Washington. A lawyer and formidable mind, he was one of New York’s delegates at the Philadelphia convention and led the Federalist faction, calling for a strong central government. Washington named him first Secretary of the Treasury. His economic policies helped create a foundation on which a national economy could grow. An opponent of Jefferson, he helped create the Federalist Party in the 1790s. He was killed in a duel with Vice-POTUS Aaron Burr in 1804. James Madison (1751-1836): A wee man with a weak constitution, he was one of the most brilliant thinkers of his age. He is called the “Father of the Constitution”: he led the Virginia delegation at the convention; kept notes on convention proceedings; devised the Virginia Plan; and, with Hamilton, led the Federalist faction. To satisfy foes of the Constitution, he wrote the Bill of Rights (1791). He joined Jefferson’s Republican Party in the mid-1790s. He was the fourth POTUS (1809-1817). Separation of Powers: Built on Montesquieu’s idea of “divided sovereignty,” this divides power and authority among three branches of government so that government will not become too powerful. Checks and Balances: This system gives each branch of government a check (control) on the power of the other branches and thereby balances power among the three. Virginia Plan: Conceived by Madison and offered by Edmund Randolph, it aimed to overhaul of the Articles and create a stronger central government: a bicameral legislature with representation based on population; a strong executive and judiciary selected by the legislature—also known as the “Large States Plan.” New Jersey Plan: a.k.a. the “Small States Plan,” offered by William Paterson of New Jersey. It proposed tweaking Articles: keeping the unicameral legislature, but giving the national government the power to impose and collect taxes and to regulate trade; and creating a national judiciary. It kept the concepts of the confederation, maintaining the sovereignty of the individual states. Connecticut Compromise: offered by Roger Sherman of Connecticut, it split the difference on the question of how representation would be determined. Following the Large States Plan, it called for a bicameral legislature with the lower house having proportional representation (by population), but the upper chamber would have equal representation (two Senators selected by each state). WE THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES, in order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, ensure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish the Constitution for the United States of America