How to Write a Sonnet

advertisement

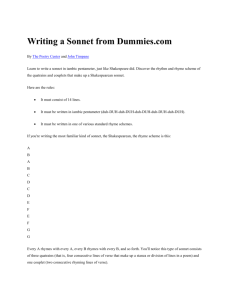

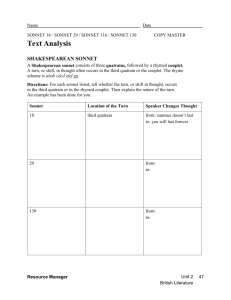

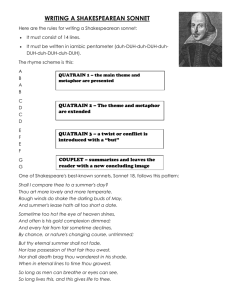

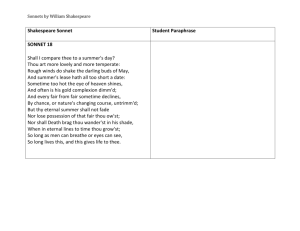

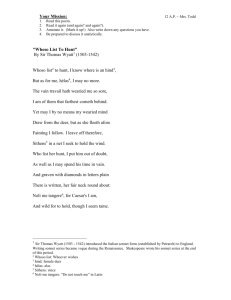

Shakespearean Sonnets: A How-To Guide The man who writes a good love sonnet needs not only to be enamored of a woman, but also to be enamored of the sonnet. ~C.S. Lewis~ Sonnet 73 That time of year thou mayst in me behold When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, Bare ruin'd choirs, where late the sweet birds sang. In me thou seest the twilight of such day As after sunset fadeth in the west, Which by and by black night doth take away, Death's second self, that seals up all in rest. In me thou see'st the glowing of such fire That on the ashes of his youth doth lie, As the death-bed whereon it must expire Consumed with that which it was nourish'd by. This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong, To love that well which thou must leave ere long. On first glance, this might just seem like a regular old poem, but we would be doing the sonnet a great injustice if we thought that. The sonnet is actually a carefully crafted argument that builds in a very particular way. There are 3 types of sonnets: Shakespearean, Petrarcan, and Scottish We Will focus on Shakespearean sonnets Structure • 14 lines • Each line contains 10 syllables and is written in iambic pentameter (duh-DUH-duh-DUHduh-DUH-duh-DUH-duh-DUH) – That means 5 iambs per line! • A-B-A-B C-D-C-D E-F-E-F G-G • Sections: – 3 Quatrains: 4 lines each (ABAB CDCD EFEF) – Couplet: 2 lines (GG) Quatrain #1: These four lines introduce the main metaphor and theme of the sonnet. That time of year thou mayst in me behold When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, Bare ruin'd choirs, where late the sweet birds sang. Here, we find out that this poem is about a man who’s growing old. He’s comparing his life to the changing of the seasons. The year is coming to a close as fall slowly gives way to winter, and so too is his life. In the first line he makes it clear that he is addressing another person, as he uses the word “thou.” This is the first stage of the sonnet’s argument. Quatrain #2: The metaphor and the theme are continued and a creative illustration is usually given to further the ideas of the first quatrain. In me thou seest the twilight of such day As after sunset fadeth in the west, Which by and by black night doth take away, Death's second self, that seals up all in rest. We see the same theme continued here, only now the man has shifted from comparing himself to the end of the year to the end of a day. He has narrowed down his argument from a year to a day. This makes the poem seem more urgent because days pass much more quickly than years do. The creative example we see here is the reference to night being “death’s second self.” Quatrain #3: Here, one of two things occurs: the metaphor is extended, or a twist or conflict is brought into the sonnet, known as the volta. This turn is vital and must be in the sonnet, though some writers prefer to place this in the closing couplet. In me thou see'st the glowing of such fire That on the ashes of his youth doth lie, As the death-bed whereon it must expire Consumed with that which it was nourish'd by. Here, the argument continues and the metaphor shifts to something even more fleeting than a day—a dying fire. Shakespeare chooses not to include the volta here; he decides to keep it for the last two lines of the poem. Let’s take a look at it that so you can see how it functions in the sonnet. Couplet: These two lines summarize the entire sonnet and give the reader something new to think about. They often act as the “thesis” of the poem. This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong, To love that well which thou must leave ere long. Here, Shakespeare does not continue with another metaphor. Rather, he gives us the volta that must be in the sonnet. The speaker explains that the reason the other person loves him so strongly is because he/she knows that the speaker will soon die. They must experience all the love they can now, before he passes away. This acts as the thesis because he states that their love is strong, and uses the first three quatrains to tell us why their love is strong. Now that you know all the different sections of the Shakespearean sonnet and understand how each one functions, you’re almost ready to write one of your own. To recap - All sonnets require the following stylistically: 1. 3 quatrains 2. 1 couplet 3. 14 lines 4. ABABCDCDEFEFGG rhyme scheme 5. Iambic pentameter Let’s take one more look at Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73 so that you can see how each of these are included. Sonnet 73 That time of year thou mayst in me behold When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, Bare ruin'd choirs, where late the sweet birds sang. In me thou seest the twilight of such day As after sunset fadeth in the west, Which by and by black night doth take away, Death's second self, that seals up all in rest. In me thou see'st the glowing of such fire That on the ashes of his youth doth lie, As the death-bed whereon it must expire Consumed with that which it was nourish'd by. This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong, To love that well which thou must leave ere long. Clear your desks of everything but your notes, a pen/pencil and a sheet of paper Time for a (sort of) pop quiz! • What type of sonnet are we focusing on? • How many lines are in a sonnet? • What is the line/meter scheme in which sonnets are • • • • • • • written? How many lines are in a quatrain? How many quatrains are in a sonnet? In a sonnet, how many “iambs” are there in each line? What is the rhyme scheme of a sonnet? What is the turn or twist in a sonnet called? The last two lines of a sonnet are called: What is the function of the last two lines? • EXTRA CREDIT: Name one other type of sonnet Let’s start by brainstorming. Make sure you have a paper and pencil handy. A good eraser is also recommended! Now, let’s begin. What do you want to say in your sonnet? A lot of sonnets pertain to love in some way, but yours doesn’t have to. If you are having trouble coming up with some ideas, here are some things to think about: -school -sports -losing a loved one -falling in love -a pet -a problem -an emotion Now that you have your topic, think of a metaphor that you want to use throughout your sonnet. Try to think of something that wouldn’t normally be compared to your topic, and then figure out ways that they are similar. Once you have your metaphor and how you want to compare it to your topic, write it down so you don’t forget it later. Now you are ready to begin composing. Make sure that you use only 10 syllables in each line, and do your best to keep them all in iambic pentameter. Also, choose your words that come at the end of each line carefully; remember that another word will need to rhyme with it. Also remember that you want to introduce your topic and your metaphor here. Hint: If you’re having trouble with iambic pentameter, go back to Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73 and read each line to this beat: duhDUH-duh-DUH-duh-DUH-duh-DUH-duh-DUH. Quatrain 1: 1. ___________________________________________________________ a 2. ___________________________________________________________ b 3. ___________________________________________________________ a 4. ___________________________________________________________ b Here, you want to continue your metaphor and your argument, but you want to build on what you wrote in the first quatrain. Remember that you are setting up for an eventual turn that will come either in the next quatrain or in the couplet, so be preparing for that. Quatrain 2: 5. ___________________________________________________________ c 6. ___________________________________________________________ d 7. ___________________________________________________________ c 8. ___________________________________________________________ d Here is where it starts getting even more exciting! Hang tough; it’s hard to write a sonnet and you may be feeling frustrated, but you can do it. This is where a lot of Shakespearean sonnets bring in the volta, or the turn. How can you shift your argument through the use of your metaphor? Do that here in this quatrain. Or, if you wish, save the twist for the final couplet, and build up your metaphor some more here. Quatrain 3: 9. ___________________________________________________________ e 10. ___________________________________________________________ f 11. ___________________________________________________________ e 12. ___________________________________________________________ f Okay, we’ve come to the final couplet. Make sure to put your turn here if you haven’t done so yet. This is where you need to summarize your argument—remember to think of it as your thesis. Why do the previous twelve lines matter? Also remember that this is a couplet, so both lines will rhyme at the end. Couplet: 13. ___________________________________________________________ g 14. ___________________________________________________________ g Now put your sonnet together. All of your lines should come together in the following manner: 1. ______________________________________________________________ a 2. ______________________________________________________________ b 3. ______________________________________________________________ a 4. ______________________________________________________________ b 5. ______________________________________________________________ c 6. ______________________________________________________________ d 7. ______________________________________________________________ c 8. ______________________________________________________________ d 9. ______________________________________________________________ e 10. ______________________________________________________________ f 11. ______________________________________________________________ e 12. ______________________________________________________________ f 13. ______________________________________________________________ g 14. ______________________________________________________________ g